We had some discussion about Macaulay on X and I wanted to write a piece about it, but I also know I probably wont get the time soon, so I am going to just copy and paste the discussion here, I am sure people can follow what is going on and offer their comments.. (Modi’s speech link at end, macaulay minute text link as well)

It started with this tweet from Wall Street Journal columnist Sadanand Dhume:

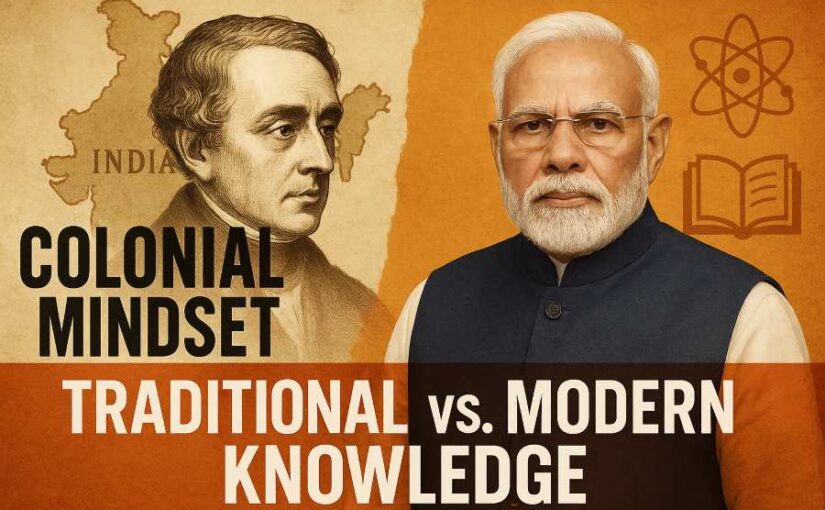

In India, critics of the 19th century statesman Thomas Macaulay portray him as some kind of cartoon villain out to destroy India. In reality, he was a brilliant man who wished Indians well. Link to article.

I replied:

I have to disagree a bit with sadanand here bcz I think while cartoonish propaganda can indeed be cartoonish and juvenile, there is a real case to be made against the impact of Macaulay on India.. Education in local languages with hindustami or even English (or for that matter, sanskrit or Persian, as they had been in the past during pre islamicate-colonization India and islamicate India respectively) as lingua franca would have been far superior, and the man really did have extremely dismissive and prejudiced views, the fact that they were common views in his world explains it but does not excuse it. The very fact that many liberal, intelligent and erudite Indians of today think he was “overall a good thing” is itself an indication that his work has done harm.. BTW, there were englishmen in India then who argued against Macaulay on exactly these lines..

Akshay Saseendran (@Island_Thought) replied:

Always believe that the past shouldnt be judged by the yardsticks of today… But Macauclay for better or worse brought English education to India which openned the doors to modern learning for a country whose education system at that point in time was fossilized to say the least. Wouldnt expect say elementary science in the 1800s to be in the vernacular when the money spent on education itself was miniscule… Also this has contributed to atleast India’s relative advantage when it comes to an English speaking workforce which can earn decent foreign exchange.

Me:

I agree that we cannot judge the past by the yardsticks of today, but that was not the question. ALL Asian cultures and countries were scientifically and economically far behind Europe in 1835 and all paid the price in various ways. Some of the elites tried to adopt western knowledge and methods and Japan actually succeeded at first attempt, others took a more roundabout route.. places like Turkey, Egypt, Thailand, Vietnam, Korea, China all learned new knowledge. But none of them abandoned their own language as medium of instruction in the long run and over time they have managed to develop fairly modern educational systems in their own languages. There is no reason why various Indian subcultures could not have done the same. Or rather, there may be reasons, but they represent Indian weaknesses, not some sort of superior choice made by India.. the aim of national development is not earning foreign exchange by being better able to serve in some foreign army after all :)_

To which Vinod (@vinodkumarpm1) replied:

A minor point. If British had decided an Indian language for higher education it would have been Persian. Persian was the official language in most part of India when British arrived. I had read that British chose English over Persian to reduce the chances of a future Indian rebellion. From a Hindu perspective, English was always preferable to Persian as Persian is considered as the language of Islamic rule and supremacy.

Me: Possible. Though they could also have picked hindustani.. they were more comfortable with it and so were many Indians.. It was definitely considered for this role, but English was picked because of the reasons enumerated by Macaulay

Meanwhile Akshay added:

Agree to some parts… But India currently has 22 official languages… The countries you just mentioned are literarily homogenous Nations with a same lingua franca! That is not the case here… Also subcultures developing indivisually without contributing to the national whole creates risk of Balkanization

me:

1. My point is not that English should or could now be replaced easily or even needs to be replaced.. history creates its own new realities. By now, it is also an Indian language, but the theoretical argument still matters because the argument is less about what language to use today and more about how one sees history and Indian culture vs Anglo culture and whether one conceives of India as inherently incapable of certain things or just that accidents of history led to X instead of Y and WE are adapting and adopting on our own terms. That also changes how one deals with realities today and tomorrow.. an anti-macaulayite can also write in english and continue to teach in IIT in English, but his vision does create a pressure at every decision point to promote a more culturally rooted alternative. What would have happened if Macaulay had gone with the suggestion to use indian languages and if Indians had written their own version instead of adopting macaulay’s vision of the worth of this vs that is also an argument about how one sees India and its potential and its worth.. that is also part of why we have this argument. The thought is that the same impulses that make us favor macaulay’s views also affect how we make NON-LANGUAGE related decisions today, not in 1835.

I think I had a point 2 in mind, but by now I am not sure what it was.

Meanwhile, on the question of alternatives, here is a long tweet from user @shrutammegopaya

This isn’t true. First let’s try to understand who Macaulay was arguing against. There were two camps who opposed his “minute” on education – 1. The Orientalists – led by HT Prinsep, HH Wilson, Lancelot Wilkinson 2. The Vernacularists – led by Brian Hodgson, William Adam The strawman that is erected is that Indians would’ve been deprived of “Enlightenment” advancements in Europe but for Macaulay. But neither the Orientalists nor the Vernacularists argued for statism where education in India is untouched by advancements in the West. Orientalists – argued for a model where western science gets grafted on to the Sanskritic tradition, through translations which many of these orientalists were working on. E.g. Charles Hutton’s early 19th cen textbook on Mathematics was already translated (or being translated) into Sanskrit around the time Macaulay was writing his minute! Lancelot Wilkinson’s “Sehore” experiments in central India are another case in point where the heliocentric model was taught to local brahmins , and attempts were made to integrate it in existing brahminical learning, with successsful results! Vernacularists – offered an alternative model where vernacular languages are used as media to teach the “new” learning from Europe. WIlliam Adam made the case that a large enough network of schools already existed in Bengal that could leverage learning material in vernacular languages. This is consistent with the observations of later scholars like Dharampal and even contemporaries of that period like Thomas Munro in Madras. The Orientalists and Vernacularists lost the battle. Macaulay triumphed. The result was not some resounding success we all should be proud of. It essentially had a negative impact on education and literacy rates at the mass level with closure of traditional schools, creating a small elite (exactly as Macaulay envisaged). Even as late as 1931, Indian literacy rate was barely 9%. Likely not a big improvement from say a century earlier. Probably even a decrease (though I don’t have data to back this) W.r.t. Macaulay’s comments on single shelf of Europe vs entire Sanskrit corpus : No need to beat yourself up and wallow in shame. There were many areas where existing Indian knowledge held its own, and areas where it didn’t. The Scientific Revolution of 17th and 18th cen was a unique event. India caught up with it more slowly than it might have otherwise, thanks to Macaulay. Macaulay’s minute suited Britain the best, because his goal wasn’t “enlightenment” of India, but to create a class of anglo-literate people in India who could run the lower rungs of government. Instead of importing expensive labor from Britain. In that respect, his minute made perfect sense to the powers that be

Postscript: distantly related 🙂

A user wrote about the 19 year old memorizer news: ‘Zero’ Contribution to Society, Economy & Development But a 19-year-old fellow who shud be studying & building his future is being celebrated for something that adds nothing to our progress. Years of political theatrics hv turned our nation into circus..

I know that various groups are honoring him as part of their political or religious agenda and not all groups or agendas are necessarily harmless, but that is a separate issue. But this objection on purely economic utilitarian grounds led me to say:

A culture is more than just economics.. people also need protection from outsiders and own criminals, and people benefit from having fellow feeling, respect for law, and models of how to live and work.. They can argue about which cultural package works better but it would be ridiculous to think they can live without one.. Culture is the software that makes communal life possible. Valuing “culture” can be overdone (or misused, exploited), but it is not possible to be prosperous without one.. And this is just some of the arguments from a non religious pov for such activities.. From the pov of a believer they obviously have far more to offer..

And our own contributor @kaeshour stepped in with:

The original post is utilitarian. People *chose* to do stuff because they find it fun and enjoyable. This kid’s choice is no different from being a rock musician or a qawwal or whatever. He has learnt a performative art form, and is good at it.

Postscript 2: This is also distantly related and came up on X and @hindookissinger posted: A lot of these letters kind of tell you that there was some kind of mass brainwashing in India that had been done against Germans. All these letters when they talk of Germans, talk about them as some kind of enemy that has to be defeated. Very jarring from a modern Indian PoV..

I dont think this inaccurate, but it made me think of a topic that I have had discussions about before and I had to jump in..

Me: It is unfair to call it brainwashing.. The notion of namak halal (true to your salt) was a very powerful indic value at that time (and a good one).. It was a fair contract, these were volunteer soldiers, not draftees, they joined because it was a good career (by rural standards, the pay was good, and brits took care of the “martial races” in other ways too (Punjab still shows the effects of benefits showered on returning servicemen and their people in general) and their officers treated their men with respect.. In return the soldiers fought loyally for them.. They did not care about the propaganda as much as they cared about not losing face as cowards.. Some of the finest soldiers in the world in that domain.. There is no need to apply modern nationalist notions on peasants who were living a pre modern life.. Of course some stirrings of nationalism were already present and exceptions existed, but on the whole it was a loyal army where both sides held up their side of the bargain (there are cases where British officers risked own careers defending “their men” against some unfair action of the British govt.. Not everyone is fighting a national war, for pre modern people honor mattered more and was quite a personal and local issue, not a national one.. My grandfather was a congressite and a nationalist who had dropped out of college and become a fugitive in the public protests that followed jallianwala bagh and had no sympathy for the Army as such, but I will never forget a discussion where someone pointed to a story in a book about the British defeat at kut al amara and how the turks (who were cruel to their captives) lined them up and brought this subedar (Muslim) forward and offered him his sword back if he joined fellow Muslims against the infidel British, and the guy broke the sword on his knee and threw it away and said do you think I am such a dishonorable person (and probably died in cruel captivity as a result) .. to us the subedar seemed to be the bad guy who is slavishly serving the British Empire against his own people but my grandfather did not agree.. HE would not join the Army himself, but he knew that the people who did were honorable people and this was an honorable act..

Another postscript: From @shrutammegopaya

The rhetoric in Macaulay’s minute distorts what the debate was about in the 1830s Macaulay wasn’t arguing against brahmins trying to prove the superiority of “Enlightenment” literature over Sanskrit corpus (though his verbiage gives that impression) Macaulay’s arguments were against fellow Brits – Orientalists who made a firm case to “modernize” education in India through the medium of Sanskrit or other vernacular languages The debate was not on what to teach, but on pedagogy and medium of instruction The upshot of the Macaulayite revolution – the closure of thousands of traditional schools across the country – was a terrible, terrible thing for India

And another tweet from me that is relevant:

All such assessments imply one thing at least.. That the arguer does not believe that the various Indian polities were capable of even attempting an alternative, but I see no reason to believe this at all.. In fact the evidence suggests that the marathas were definitely conscious of the need to catch up, but more instructively, several princely states in British times were eager to adopt new learning and sometimes did a better job of it than British administered India.. The notion that all India would be a stagnant hellhole without the benevolent Raj was a feature of British propaganda, not of history.. It is itself a Macaulayputra tic to believe otherwise..

Full Text of the Famous minute on education.

2ND OF FEBRUARY, 1835

As it seems to be the opinion of some of the gentlemen who compose the Committee of Public Instruction, that the course which they have hitherto pursued was strictly prescribed by the British Parliament in 1813, and as, if that opinion be correct, a legislative act will be necessary to warrant a change, I have thought it right to refrain from taking any part in the preparation of the adverse statements which are now before us, and to reserve what I had to say on the subject till it should come before me as a member of the Council of India.

It does not appear to me that the Act of Parliament can, by any art of construction, be made to bear the meaning which has been assigned to it. It contains nothing about the particular languages or sciences which are to be studied. A sum is set apart “for the revival and promotion of literature and the encouragement of the learned natives of India, and for the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the inhabitants of the British territories.” It is argued, or rather taken for granted, that by literature, the Parliament can have meant only Arabic and Sanscrit literature, that they never would have given the honorable appellation of “a learned native” to a native who was familiar with the poetry of Milton, the Metaphysics of Locke, and the Physics of Newton; but that they meant to designate by that name only such persons as might have studied in the sacred books of the Hindoos all the uses of cusa-grass, and all the mysteries of absorption into the Deity. This does not appear to be a very satisfactory interpretation. To take a parallel case; suppose that the Pacha of Egypt, a country once superior in knowledge to the nations of Europe but now sunk far below them, were to appropriate a sum or the purpose of “reviving and promoting literature, and encouraging learned natives of Egypt,” would anybody infer that he meant the youth of his pachalic to give years to the study of hieroglyphics, to search into all the doctrines disguised under the fable of Osiris, and to ascertain with all possible accuracy the ritual with which cats and onions were anciently adored? Would he be justly charged with inconsistency, if, instead of employing his young subjects in deciphering obelisks, he were to order them to be instructed in the English and French languages, and in all the sciences to which those languages are the chief keys?

The words on which the supporters of the old system rely do not bear them out, and other words follow which seem to be quite decisive on the other side. This lac of rupees is set apart, not only for “reviving literature in India,” the phrase on which their whole interpretation is founded, but also for “the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the inhabitants of the British territories,”–words which are alone sufficient to authorise all the changes for which I contend.

If the Council agree in my construction, no legislative Act will be necessary. If they differ from me, I will prepare a short Act rescinding that clause of the Charter of 1813, from which the difficulty arises.

The argument which I have been considering, affects only the form of proceeding. But the admirers of the Oriental system of education have used another argument, which, if we admit it to be valid, is decisive against all change. They conceive that the public faith is pledged to the present system, and that to alter the appropriation of any of the funds which have hitherto been spent in encouragmg the study of Arabic and Sanscrit, would be down-right spoliation. It is not easy to understand by what process of reasoning they can have arrived at this conclusion. The grants which are made from the public purse for the encouragement of literature differed in no respect from the grants which are made from the same purse for other objects of real or supposed utility. We found a sanatarium on a spot which we suppose to be healthy. Do we thereby pledge ourselves to keep a sanatarium there, if the result should not answer our expectation? We commence the erection of a pier. Is it a violation of the public faith to stop the works, if we afterwards see reason to believe that the building will be useless? The rights of property are undoubtedly sacred. But nothing endangers those rights so much as the practice, now unhappily too common, of attributing them to things to which they do not belong. Those who would impart to abuses the sanctity of property are in truth imparting to the institution of property the unpopularity and the fragility of abuses. If the Government has given to any person a formal assurance; nay, if the Government has exdted in any person’s mind a reasonable expectation that he shall receive a certain income as a teacher or a learner of Sanscrit or Arabic, I would respect that person’s pecuniary interests–I would rather err on the side of liberality to individuals than suffer the public faith to be called in question. But to talk of a Government pledging itself to teach certain languages and certain sciences, though those languages may become useless, though those sciences may be exploded, seems to me quite unmeaning. There is not a single word in any public instructions, from which it can be inferred that the Indian Government ever intended to give any pledge on this subject, or ever considered the destination of these funds as unalterably fixed. But had it been otherwise, I should have denied the competence of our predecessors to bind us by any pledge on such a subject. Suppose that a Government had in the last century enacted in the most sole,nn manner that all its subjects should, to the end of time, be inoculated for the smallpox: would that Government be bound to persist in the practice after Jenner’s discovery? These promises, of which nobody claims the performance, and from which nobody can grant a release; these vested rights, which vest in nobody; this property without proprietors; this robbery, which makes nobody poorer, may be comprehended by persons of higher faculties than mine.— I consider this plea merely as a set form of words, regularly used both in England and in India, in defence of every abuse for which no other plea can be set up.

I hold this lac of rupees to be quite at the disposal of the Governor General in Council, for the purpose of promoting learning in India, in any way which may be thought most advisable. I hold his Lordship to be quite as free to direct that it shall no longer be employed in encouraging Arabic and Sanscrit, as he is to direct that the reward for killing tigers in Mysore shall be diminished, that no more public money shall be expended on the chanting at the cathedral.

We now come to the gist of the matter. We have a fund to be employed as Government shall direct for the intellectual improvement of the people of this country. The simple question is, what is the most useful way of employing it?

All parties seem to be agreed on one point, that the dialects commonly spoken among the natives of this part of India, contain neither literary nor scientific information, and are, moreover, so poor and rude that, until they are enriched from some other quarter, it will not be easy to translate any valuable work into them. It seems to be admitted on all sides, that the intellectual improvement of those classes of the people who have the means of pursuing higher studies can at present be effected only by means of some language not vernacular amongst them.

What then shall that language be? One-half of the Committee maintain that it should be the English. The other half strongly recommend the Arabic and Sanscrit. The whole question seems to me to be, which language is the best worth knowing?

I have no knowledge of either Sanscrit or Arabic.–But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value. I have read translations of the most celebrated Arabic and Sanscrit works. I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. The intrinsic superiority of the Western literature is, indeed, fully admitted by those members of the Committee who support the Oriental plan of education.

It will hardly be disputed, I suppose, that the department of literature in which the Eastern writers stand highest is poetry. And I certainly never met with any Orientalist who ventured to maintain that the Arabic and Sanscrit poetry could be compared to that of the great European nations. But when we pass from works of imagination to works in which facts are recorded, and general principles investigated, the superiority of the Europeans becomes absolutely immeasurable. It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say, that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanscrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England. In every branch of physical or moral philosophy, the relative position of the two nations is nearly the same.

How, then, stands the case? We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language. The claims of our own language it is hardly necessary to recapitulate. It stands pre-eminent even among the languages of the west. It abounds with works of imagination not inferior to the noblest which Greece has bequeathed to us; with models of every species of eloquence; with historical compositions, which, considered merely as nar- ratives, have seldom been surpassed, and which, considered as vehicles of ethical and political instruction, have never been equalled; with just and lively representations of human life and human nature; with the most profound speculations on metaphysics, morals, government, jurisprudence, and trade; with full and correct information respecting every experimental science which tends to preserve the health, to increase the comfort, or to expand the intellect of man. Whoever knows that language has ready access to all the vast intellectual wealth, which all the wisest nations of the earth have created and hoarded in the course of ninety generations. It may safely be said, that the literature now extant in that language is of far greater value than all the literature which three hundred years ago was extant in all the languages of the world together. Nor is this all. In India, English is the language spoken by the ruling class. It is spoken by the higher class of natives at the seats of Government. It is likely to become the language of commerce throughout the seas of the East. It is the language of two great European communities which are rising, the one in the south of Africa, the other in Australasia; communities which are every year becoming more important, and more closely connected with our Indian empire. Whether we look at the intrinsic value of our literature, or at the particular situation of this country, we shall see the strongest reason to think that, of all foreign tongues, the English tongue is that which would be the most useful to our native subjects.

The question now before us is simply whether, when it is in our power to teach this language, we shall teach languages in which, by universal confession, there are no books on any subject which deserve to be compared to our own; whether, when we can teach European science, we shall teach systems which, by universal confession, whenever they differ from those of Europe, differ for the worse; and whether, when we can patronise sound Philosophy and true History, we shall countenance, at the public expense, medi- cal doctrines, which would disgrace an English farrier,–Astronomy, which would move laughter in girls at an English boarding school,–History, abounding with kings thirty feet high, and reigns thirty thousand years long,–and Geography, made up of seas of treacle and seas of butter.

We are not without experience to guide us. History furnishes several analogous cases, and they all teach the same lesson. There are in modern times, to go no further, two memorable instances of a great impulse given to the mind of a whole society,–of prejudices overthrown,–of knowledge diffused,–taste purified,–of arts and sciences planted in countries which had recently been ignorant and barbarous.

The first instance to which I refer, is the great revival of letters among the Western nations at the close of the fifteenth and the begi:ning of the sixteenth century. At that time almost every thing that was worth reading was contained in the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Had our ancestors acted as the Committee of Public Instruction has hitherto acted; had they neglected the language of Cicero and Tacitus; had they confined their attention to the old dialects of our own island; had they print- ed nothing and taught nothing at the universities but Chronicles in Anglo-Saxon, and Romances in Norman-French, would England have been what she now is? What the Greek and Latin were to the contemporaries of More and Ascham, our tongue is to the people of India. The literature of England is now more valuable than that of classical antiquity. I doubt whether the Sanscrit literature be as valuable as that of our Saxon and Norman progenitors. In some departments,–in History, for example, I am certain that it is much less so.

Another instance may be said to be still before our eyes. Within the last hundred and twenty years, a nation which has previously been in a state as barbarous as that in which our ancestors were before the crusades, has gradually emerged from the ignorance in which it was sunk, and has taken its place among civilized communities.–I speak of Russia. There is now in that country a large educated class, abounding with persons fit to serve the state in the highest ftmctions, and in no wise inferior to the most accomplished men who adorn the best circles of Paris and London. There is reason to hope that this vast empire, which in the time of our grandfathers was probably behind the Punjab, may, in the time of our grandchildren, be pressing close on France and Britain in the career of improvement. And how was this change effected? Not by flattering national prejudices: not by feeding the mind of the young Muscovite with the old women’s stories which his rude fathers had believed: not by filling his head with lying legends about St. Nicholas: not by encouraging him to study the great question, whether the world was or was not created on the 13th of September: not by calling him “a learned native,” when he has mastered all these points of knowledge: but by teaching him those foreign languages in which the greatest mass of information had been laid up, and thus putting all that information within his reach. The languages of Western Europe civilized Russia. I cannot doubt that they will do for the Hindoo what they have done for the Tartar.

And what are the arguments against that course which seems to be alike recommended by theory and by experience? It is said that we ought to secure the cooperation of the native public, and that we can do this only by teaching Sanscrit and Arabic.

I can by no means admit that when a nation of high intellectual attainments undertakes to Superintend the education of a nation comparatively ignorant, the learners are absolutely to prescribe the course which is to be taken by the teachers. It is not necessary, however, to say any thing on this subject. For it is proved by unanswerable evidence that we are not at present securing the Cooperation of the natives. It would be bad enough to consult their intellectual taste at the expense of their intellectual health. But we are consulting neither,–we are withholding from them the learning for which they are craving, we are forcing on them the mock-learning which they nauseate.

This is proved by the fact that we are forced to pay our Arabic and Sanscrit students, while those who learn Engiish are wiling to pay us. All the declamations in the worid about the love and reverence of the natives for their sacred dialects will never, in the mind of any impartial person, outweigh the undisputed fact, that we cannot find, in all our vast empire, a single student who will let us teach him those dialects unless we will pay him.

I have now before me the accounts of the Madrassa for one month,-in the month of December, 1833. The Arabic students appear to have been seventy-seven in number. All receive stipends from the public. The whole amount paid to them is above 500 rupees a month. On the other side of the account stands the following item: Deduct amount realized from the out-students of English for the months of May, June and July last, 103 rupees.

I have been told that it is merely from want of local experience that I am surprised at these phenomena, and that it is not the fashion for students in India to study at their own charges. This only confirms me in my opinion. Nothing is more certain than that it never can in any part of the world be necessary to pay men for doing what they think pleasant and profitable. India is no exception to this rule. The people of India do not require to be paid for eating rice when they are hungry, or for wearing woollen cloth in the cold season. To come nearer to the case before us, the children who learn their letters and a little elementary Arithmetic from the village school-master are not paid by him. He is paid for teaching them. Why then is it necessary to pay people to learn Sanscrit and Arabic? Evidently because it is universally felt that the Sanscrit and Arabic are languages, the knowledge of which does not compensate for the trouble of acquiring them. On all such subjects the state of the market is the decisive test.

Other evidence is not wanting, if other evidence were required. A petition was presented last year to the Committee by several ex-students of the Sanscrit College. The petitioners stated that they had studied in the college ten or twelve years; that they had made themselves acquainted with Hindoo literature and science; that they had received certificates of proficiency: and what is the fruit of all this! “Notwithstanding such testimonials,” they say, “we have but little prospect of bettering our condition without the kind assistance of your Honorable Committee, the indifference with which we are generally looked upon by our countrymen leaving no hope of encouragement and assistance from them.” They therefore beg that they may be recommended to the Governor General for places under the Government, not places of high dignity or emolument, but such as may just enable them to exist. “We want means,” they say, “for a decent living, and for our progressive improvement, which, however, we cannot obtain without the assistance of Government, by whom we have been educated and maintained from childhood.” They conclude by representing, very pathetically, that they are sure that it was never the intention of Government, after behaving so liberally to them during their education, to abandon them to destitution and neglect.

I have been used to see petitions to Government for compensation. All these petitions, even the most unreasonable of them, proceeded on the supposition that some loss had been sustained- that some wrong had been inflicted. These are surely the first petitioners who ever demanded compensation for having been educated gratis, for having been supported by the public during twelve years, and then sent forth into the world well furnished with literature and science. They represent their education as an injury which gives them a claim on the Government for redress, as an injury for which the stipends paid to them during the infliction were a very inadequate compensation. And I doubt not that they are in the right. They have wasted the best years of life in learning what procures for them neither bread nor respect. Surely we might, with advantage, have saved the cost of making these persons useless and miserable; surely, men may be brought up to be burdens to the public and objects of contempt to their neighbours at a somewhat smaller charge to the state. But such is our policy. We do not even stand neuter in the contest between truth and falsehood. We are not content to leave the natives to the influence of their own hereditary prejudices. To the natural difficulties which obstruct the progress of sound science in the East, we add fresh difficulties of our own making. Bounties and premiums, such as ought not to be given even for the propagation of truth, we lavish on false taste and false philosophy.

By acting thus we create the very evil which we fear. We are making that opposition which we do not find. What we spend on the Arabic and Sanscrit colleges is not merely a dead loss to the cause of truth; it is bounty-money paid to raise up champions of error. It goes to form a nest, not merely of helpless place-hunters, but of bigots prompted alike by passion and by interest to raise a cry against every usetul scheme of education. If there should be any opposition among the natives to the change which I recommend, that opposition will be the effect of our own system. It will be headed by persons supported by our stipends and trained in our colleges. The longer we persevere in our present course, the more formidable will that opposition be. It will be every year reinforced by recruits whom we are paying. From the native society left to itself, we have no difficulties to apprehend; all the murmuring will come from that oriental interest which we have, by artificial means, called into being, and nursed into strength.

There is yet another fact, which is alone sufficient to prove that the feeling of the native public, when left to itself, is not such as the supporters of the old system represent it to be. The Committee have thought fit to lay out above a lac of rupees in printing Arabic and Sanscrit books. Those books find no purchasers. It is very rarely that a single copy is disposed of. Twenty-three thousand volumes, most of them folios and quartos, fill the libraries, or rather the lumber-rooms, of this body. The Committee contrive to get rid of some portion of their vast stock of oriental literature by giving books away. But they cannot give so fast as they print. About twenty thousand rupees a year are spent in adding fresh masses of waste paper to a hoard which, I should think, is already sufficiently ample. During the last three years, about sixty thousand rupees have been expended in this manner. The sale of Arabic and Sanscrit books, during those three years, has not yielded quite one thousand rupees. In the mean time the School- book Society is selling seven or eight thousand English volumes every year, and not only pays the expenses of printing, but realises a profit of 20 per cent. on its outlay.

The fact that the Hindoo law is to be learned chiefly from Sans- crit books, and the Mahomedan law from Arabic books, has been much insisted on, but seems not to bear at all on the question. We are commanded by Parliament to ascertam and digest the laws of India. The assistance of a law Commission has been given to us for that purpose. As soon as the code is promulgated, the Shasster and the Hedaya will be useless to a Moonsiff or Sudder Ameen. I hope and trust that before the boys who are now entering at the Madrassa and the Sanscrit college have completed their studies, this great work will be finished. It would be manifestly absurd to educate the rising generation with a view to a state of things which we mean to alter before they reach manhood.

But there is yet another argument which seems even more untenable. It is said that the Sanscrit and Arabic are the languages in which the sacred books of a hundred millions of people are written, and that they are, on that account, entitled to peculiar encouragement. Assuredly it is the duty of the British Government in India to be not only tolerant, but neutral on all religious questions. But to encourage the study of a literature admitted to be of small intrinsic value, only because that literature incuIcates the most serious errors on the most important subjects, is a course hardly reconcileable with reason, with morality, or even with that very neutrality which ought, as we all agree, to be sacredly pre- served. It is confessed that a language is barren of useful know- ledge. We are to teach it because it is fruittul of monstrous superstitions. We are to teach false History, false Astronomy, false Medicine, because we find them in company with a false religion. We abstain, and I trust shall always abstain, from giving any public encouragement to those who are engaged in the work of converting natives to Christianity. And while we act thus, can we reasonably and decently bribe men out of the revenues of the state to waste their youth in learning how they are to purify themselves after touching an ass, or what text of the Vedas they are to repeat to expiate the crime of killing a goat?

It is taken for granted by the advocates of Oriental learning, that no native of this country can possibly attain more than a mere smattering of English. They do not attempt to prove this; but they perpetually insinuate it. They designate the education which their opponents recommend as a mere spelling book education. They assume it as undenlable, that the question is between a profound knowledge of Hindoo and Arabian literature and science on the one side, and a superficial knowledge of the rudiments of English on the other. This is not merely an assumption, but an assumption contrary to all reason and experience. We know that foreigners of all nations do learn our language sufficiently to have access to all the most abstruse knowledge which it contains, sufficiently to relish even the more delicate graces of our most idiomatic writers. There are in this very town natives who are quite competent to discuss political or scientific questions with fluency and precision in the English language. I have heard the gentlemen with a liberality and an intelligence which would do credit to any member of the Committee of Public Instruction. Indeed it is unusual to find, even in the literary circles of the continent, any foreigner who can express himself in English with so much facility and correctness as we find in many Hindoos. Nobody, I suppose, will contend that English is so difficult to a Hindoo as Greek to an Englishman. Yet an intelligent English youth, in a much smaller number of years than our unfortunate pupils pass at the Sanscrit college, becomes able to read, to enjoy, and even to imitate, not unhappily, the compositions of the best Greek Authors. Less than half the time which enables an English youth to read Herodotus and Sophocles, ought to enable a Hindoo to read Hume and Milton.

To sum up what I have said, I think it clear that we are not fettered by the Act of Parliament of 1813; that we are not fettered by any pledge expressed or implied; that we are free to employ our fiinds as we choose; that we ought to employ them in teaching what is best worth knowing; that English is better worth knowing than Sanscrit or Arabic; that the natives are desirous to be taught English, and are not desirous to be taught Sanscrit or Arabic; that neither as the languages of law, nor as the languages of religion, have the Sanscrit and Arabic any peculiar claim to our engagement; that it is possible to make natives of this country thoroughly good English scholars, and that to this end our efforts ought to be directed.

In one point I fully agree with the gentlemen to whose general views I am opposed. I feel with them, that it is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

I would strictly respect all existing interests. I would deal even generously with all individuals who have had fair reason to expect a pecuniary provision. But I would strike at the root of the bad system which has hitherto been fostered by us. I would at once stop the printing of Arabic and Sanscrit books, I would abolish the Madrassa and the Sanscrit college at Calcutta. Benares is the great seat of Brahmanical learning; Delhi, of Arabic learning. If we retain the Sanscrit college at Benares and the Mahometan college at Delhi, we do enough, and much more than enough in my opinion, for the Eastern languages. If the Benares and Delhi colleges should be retained, I would at least recommend that no stipends shall be given to any students who may hereafter repair thither, but that the people shall be left to make their own choice between the rival systems of education without being bribed by us to learn what they have no desire to know. The funds which would thus be placed at our disposal would enable us to give larger encouragement to the Hindoo college at Calcutta, and to establish in the principal cities throughout the Presidencies of Fort William and Agra schools in which the English language might be well and thoroughly taught.

If the decision of his Lordship in Council should be such as I anticipate, I shall enter on the performance of my duties with the greatest zeal and alacrity. If, on the other hand, it be the opinion of the Government that the present system ought to remain unchanged, I beg that I may be permitted to retire from the chair of the Committee. I feel that I could not be of the smallest use there–I feel, also, that I should be lending my countenance to what I firmly believe to be a mere delusion. I believe that the present system tends, not to accelerate the progress of truth, but to delay the natural death of expiring errors. I conceive that we have at present no right to the respectable name of a Board of Public Instruction. We are a Board for wasting public money, for printing books which are of less value than the paper on which they are printed was while it was blank; for giving artificial encouragement to absurd history, absurd metaphysics, absurd physics, absurd theology; for raising up a breed of scholars who find their scholarship an encumbrance and a blemish, who live on the public while they are receiving their education, and whose education is so utterly useless to them that when they have received it they must either starve or live on the public all the rest of their lives. Entertaining these opinions, I am naturally desirous to decline all share in the responsibility of a body, which unless it alters its whole mode of proceeding, I must consider not merely as useless, but as positively noxious.

Interesting if English is as alien to a Tamilian as it is to a Hindi speaker.

I wonder if the Indo-European link makes any difference.

The Dravidian states seem to prefer one Aryan language (English) to another (Hindu).

wasn’t Macaulay the one who said one shelf of English is worth more than the whole South Asian corpus..

He did, but in retrospect that was only true of some forms of empirical knowledge in 1835, and there being more to working culture than empirical knowledge, his statement was not accurate even in 1835..

South Indians prefer English to Hindi because they see Hindi as a North Indian imposition. If it weren’t forced on them, they probably would have less issues with it.

In Pakistan’s case, imposing Urdu on East Pakistan was one of the causes of the breakup of the country–maybe not the main cause but it was certainly important.

American Missionaries familiarized Tamil Nadu with English and Science. The American Missionary schools was more about teaching Science Math no Religion.

Note this the Protestant Christian denomination. The Catholics took a long while to modernize. Pre WW2 Catholics were discouraged from learning to read and wite

So the Southern Tamil Nadu went with the same way as Sri Lankas Tamils (north). Educated, competent in English and manned the British Administration, not just in TN, in Malaysia too

Dr. Anjum Altaf on Macaulay:

“Macaulay’s Stepchildren”

https://thesouthasianidea.wordpress.com/2010/01/06/macaulays-stepchildren/

An ironic contribution of Lord Macaulay’s ideas about English education in British India was that the heroes of the freedom movement (Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Nehru, QeA) were all English-educated lawyers. They used British ideas of home rule, democracy etc against the British themselves.

More recently, Dr. Anjum Altaf has been consistently arguing against teaching English from first grade or using English as the medium of instruction. Research consistently holds that students should be educated in their home language first with the national language being introduced later and then finally a choice of foreign language. He’s not against English as a subject but against English as the medium of instruction. There is no reason that Pakistani children have to be taught mathematics and science in English (particularly at the elementary levels).

For example, a child in KPK would be educated in Pashto first. Urdu would be introduced later (as the national lingua franca). Finally, English would be introduced around sixth grade (at the age of 11 or 12).

In my own case, I am much more comfortable with English than with Urdu but primarily that has to do with leaving Pakistan at the age of six and being educated entirely abroad. My parents were educated at English language convent schools in Lahore and yet are able to read literary poetry (Ghalib, Faiz etc) in Urdu.

I have had to make great efforts in adulthood to improve my facility in reading Urdu. Mainly, this has to do with the script. If Urdu were written in the Roman alphabet (like Turkish is for example) I would probably have had an easier time.

Edit: I’m speaking specifically about reading ability. My spoken Urdu is fine. A six year old child already has a fairly good grasp of spoken language. Also, my parents did make an effort to speak Urdu at home even when we lived in the US. Finally, my participation in Hindustani classical music (particularly the singing of Ghazals) made sure that familiarity with the sounds of spoken Urdu/Hindustani was not a problem.

it’s always the sub-elites who revolt

I personally think the National Language is important. (I studied in Sinhala Medium including Science, Math and History)

In Uni or Professional exams switch to English.

Many of those with me in Uni were from Village Schools. They could not speak English, but could read or write. By the time they graduated competent in English too.

Top Academics and researchers all over the world.

One such example, retired from Silicon Valley

https://www.linkedin.com/in/kapila-wijekoon-0a8a1b3/

I

Research shows English can be introduced in secondary school.

Many European countries have a three language formula: native language (mother tongue) first, then national language, then a foreign language (which is usually English).

We have all three languages by Grade 5

we need to learn more about Sri Lanka

All of this reminded me of Dr Nomanul Haq’s arguments in favour of Urdu as the pedagogical language:

https://www.dawn.com/news/1644543

I don’t think one can seriously argue that Pashto is not the “mother tongue” of (most) children in KPK or Balochi of (most) children in Balochistan.

Of course, Urdu is not alien to Pakistani children in the way that English is but the research does indicate that it is best for children to be educated first in their “mother tongue” or home language.

And I say this as someone whose “mother tongue” is actually Urdu. Despite the fact that my nani nana spoke Punjabi to each other, they were so impressed by QeA’s making Urdu the “national language” that they spoke Urdu to their children. On my dad’s side, his mother was from Agra so they also spoke Urdu at home.

KPK & Baluchistan aren’t overwhelming Pashtun and Baluch right?

I think KPK is overwhelmingly Pashtun. Balochistan has some areas which are Pashtun (as far as I know).

what are your thoughts on Urdu

“The notion that all India would be a stagnant hellhole without the benevolent Raj was a feature of British propaganda, not of history.. It is itself a Macaulayputra tic to believe otherwise..”

Wise words

yes India’s Golden Age was probably 1000 AD

I did want to write on this excellent post

[…] Follow-Up to Macaulay, Macaulayputras, and their discontents […]