1) “Dargahs Beyond Belief” by Shah Umair

2) “After Khaleda and Hasina: What lies ahead for Bangladesh and India?”

3) “Politics of History: Manu Pillai with Salil Tripathi”

4) Trump is ‘Chest Beating’ Over a Retreat| ‘The Opinions’ Podcast

1) “Dargahs Beyond Belief” by Shah Umair

2) “After Khaleda and Hasina: What lies ahead for Bangladesh and India?”

3) “Politics of History: Manu Pillai with Salil Tripathi”

4) Trump is ‘Chest Beating’ Over a Retreat| ‘The Opinions’ Podcast

The Clip That Explained a Civilisation

A short video of an Iranian woman is circulating on X. In it, she says Islam is not Iran’s native religion and was imposed on Zoroastrian Persians through torture, massacre, rape, and enslavement. The clip is amplified by familiar accelerants, including Tommy Robinson, and is now being treated as a one-line explanation for a fourteen-century transformation.

Almost immediately, a counter-narrative appears. It insists there is “not a single piece of evidence” for forced conversion in Persia; that Islamisation was slow; and that many Persians, especially Sasanian elites, moved toward the new order for political, fiscal, and social reasons. A further layer is added: nostalgia for the Sasanians is misplaced because late Sasanian society was rigid, unequal, and harsh, and early Muslim rule improved conditions for ordinary people. These are two different claims. They are routinely fused. History does not require that fusion.

Conquest Is Not Conversion Continue reading Between Arab Conquest and Persian Conversion: The Sasanian Inheritance

Every few months someone asks whether Brown Pundits is “dying.” I understand the instinct. The internet is littered with abandoned blogs. Attention is fickle. Writers drift. The centre does not hold. And yet, when I actually look at the numbers, the mood often turns out to be wrong.

We had a real dip. In September and October we were running at roughly 55–65k monthly readers. Then we fell hard, to around 33k. This month, we have bounced back to roughly 53k. That is a 60% jump on the trough. A lot of it is mobile. A lot of it is casual readership rather than the old-school desktop cohort. But it is still real people arriving, reading, and sharing.

The geographical pattern is also telling. India and the United States remain the main pillars, as you would expect. But Bangladesh has surged in a way we did not anticipate. That matters because it suggests we are not only a niche diaspora salon. We are also being read inside the region, by people who do not need South Asia explained to them. Continue reading The Demise of Brown Pundits Is Much Exaggerated

I am recovering from jet lag, so I will keep this short and plain. The clip circulating makes a distinction that is worth sitting with: empires that incorporate versus empires that extract.

The empires usually placed in the first category, Chinese, Ottoman, Mughal, expanded by absorbing populations into an existing civilisational framework. They taxed, yes, but they also governed. Local elites were co-opted rather than liquidated. Customary law survived. Grain moved when harvests failed. The empire’s legitimacy rested on continuity: rule was justified by order, stability, and the promise that tomorrow would look broadly like yesterday.

The empires in the second category, French, English, Dutch, were different in kind. They were commercial projects backed by force. Their logic was not incorporation but throughput. Territories were valuable insofar as they yielded revenue, commodities, or strategic advantage. Administration was thin. Local welfare was incidental. When extraction worked, it worked spectacularly. When it failed, it failed catastrophically. Continue reading Empire of Incorporation versus Empire of Extraction

Endogamy Is Optional When You Own the Institutions

Gaurav’s excellent piece on “progressive Dravidianism” pushed me to re-examine a related elite anxiety: the melodrama around intermarriage. I am happy to be corrected on any of the specifics below, especially where a claim could be tightened with better data.

The standard story goes like this. Elites marry out. Boundaries dissolve. The group dies. This story is intuitively appealing because it treats identity as if it were a biological substance. But elites are not reproduced primarily by blood. They are reproduced by property, institutions, credentials, and networks. In that world, intermarriage is rarely a solvent. It is more often a merger.

The English aristocracy understood this early, and acted accordingly. When the old landed families were cash-poor but title-rich, they did not preserve themselves by sealing the gates. They did the opposite. They married in money. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries produced a whole genre of “dollar princesses,” wealthy American heiresses who married British aristocrats, trading capital for rank. By one commonly cited compilation, between 1870 and 1914, over a hundred British aristocrats, including multiple dukes, married American women; and in the broader European set, hundreds of such transatlantic matches were recorded. This was not cultural dilution. It was institutional self-preservation by acquisition. The class survived because it treated marriage as capital strategy. Continue reading Bollywood, Brahmins, Parsis & WASPs:

Chennai, without any doubt, is one of the better cities in the country. I agree with many of the issues raised by XTM here. Along with Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, and Bangalore, Chennai continues to fare better in many aspects of life compared to Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, and even Pune.

While I appreciated the cleanliness and infrastructure of Chennai, I cannot say I came away with the same impression as XTM. Of all the Indian cities I have visited, I found Chennai less hospitable than Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, or Delhi. Even as a fluent English speaker, I struggled to hail autos or get directions. Surprisingly, I did not face this issue in the rest of Tamil Nadu. For older Hindi speakers with limited English, the experience is even worse. The issue is not simply language, but linguistic chauvinism (also present in Karnataka and Maharashtra, though to a lesser extent). A non-Tamil speaker often looks for Muslim individuals to ask for help in Chennai.

I had a wonderful time in Mamallapuram, enjoying the Pallava ruins and the beach, thanks to a very helpful Muslim auto driver. But enough of auto-wala stories.

Without comparing cities directly, it is important to recognize that culture may play a role in Chennai’s successes. However, correlation should not be confused with causation, and credit should not be misplaced. Any link between Chennai’s well-being and Dravidianism is tenuous or purely incidental at best. While successive Tamil Nadu governments aligned with Dravidianism have been relatively successful (especially compared to the North) in providing welfare nets, what direct connection do these well-run policies have with Dravidianism?

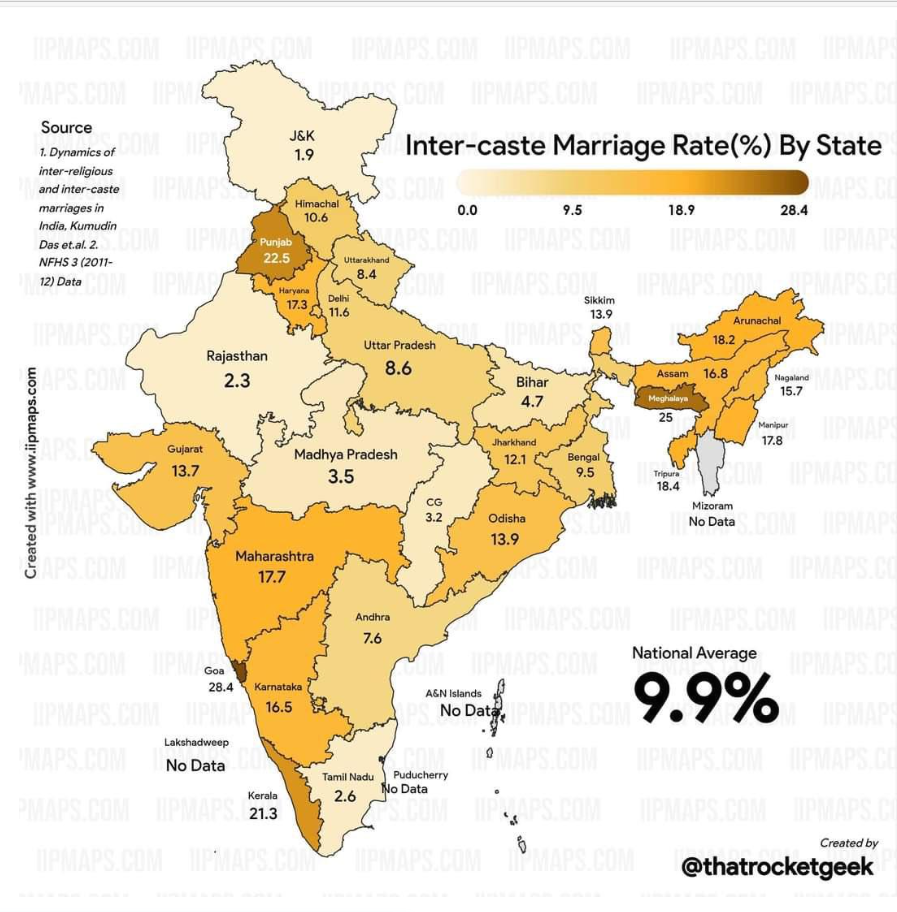

Let us compare Tamil Nadu with the rest of India on the metric that Dravidian progressivism claims to address: CASTE

Link:

Scroll piece : Caste endogamy is also unaffected by how developed or industrialised a particular state is, even though Indian states differ widely in this aspect. Tamil Nadu, while relatively industrialised, has a caste endogamy rate of 97% while underdeveloped Odisha’s is 88%, as per a study by researchers Kumudini Das, Kailash Chandra Das, Tarun Kumar Roy and Pradeep Kumar Tripathy.

Put differently: caste endogamy seems unaffected by how anti-Brahminical or “progressive” a state claims to be. Tamil Nadu, the heart of the Dravidian movement, remains at below 3%, while Gujarat—often seen as Brahmanical and vegetarian—stands around 10% (15% in a 2010 study, though possibly overstated). However one frames it, Gujarat has more inter-caste marriages than Tamil Nadu.

Surprisingly, even Haryana and Punjab—traditionally associated with Khap Panchayats and honor culture—show significant inter-caste marriages, along with Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Kerala.

While data on Haryana, Punjab, and Goa is contested, Tamil Nadu consistently lags, whereas its neighbor Kerala consistently leads, along with Maharashtra.

Crossing from Kerala into Tamil Nadu, the difference is stark: one in five marriages in Kerala are inter-caste, compared to fewer than one in thirty in Tamil Nadu. Would it be fair to blame Dravidian politics for this? That claim has more merit than attributing Tamil Nadu’s successes to Dravidianism. Tamil Nadu ranks alongside Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Kashmir, while Karnataka, Kerala, and even Andhra/Telangana are far ahead.

Even Kashmir, with a 65% Muslim population, has an inter-caste marriage rate just below 2%, lower than Dravidian-ruled Tamil Nadu. So, after 500 years under a “casteless” religion and 100 years of “progressive” Dravidianism, both Kashmir and Tamil Nadu lag behind Gujarat, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

This data does not fit neat narratives. I was surprised to see higher percentages of rural inter-caste marriages. Rates are negatively correlated with wealth and income (more strongly with assets such as land). Landed communities show stronger caste endogamy, for historically and pragmatically clear reasons. That Brahmins, as a group, have the highest inter-caste marriage rates is unsurprising, given how progressive (some might say deracinated) Brahmins have become in India.

One social metric where Tamil Nadu performs well is female foeticide. Tamil Nadu and Kerala are among the leading states less affected by sex-selective abortions compared to the rest of India.

Tamil Brahmins have generally been more socially aloof compared to Brahmins elsewhere in India (both anecdotally and objectively) and disproportionately occupied government posts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Justice Party movement, which arose in response, was initially a elite-feudal project, though Periyar’s early movement (also virulently anti-Brahmin) was more inclusive of Dalits and non-dominant castes. Over time, while retaining its anti-Brahmin rhetoric, the movement became a proxy for domination by landed and wealthy communities. Dravidianism today (or perhaps always) resembles what it claimed to oppose—Brahmanism. The dominant elites have simply shifted from Brahmins and the British to others who hold power today. Hatred alone does not create positive change.

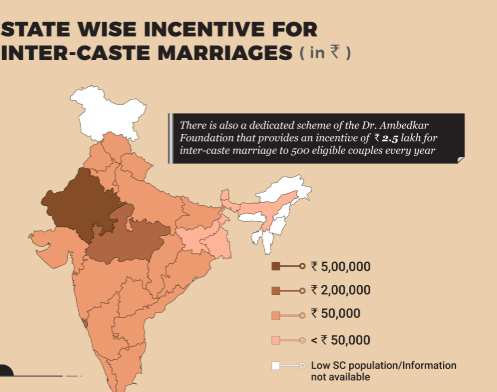

It seems Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh understood the incentives for reform, while Tamil Nadu did not.

Anecdotes or caste violence are often dismissed when praising the Dravidian model of social progressivism. Comparative caste violence data is brushed aside under claims of underreporting or lack of Dalit assertion in other regions. But caste endogamy cannot be ignored. If anything that truly encapsulates Caste is endogamy.

Post Script:

Tamil politicians, both DMK and AIADMK, have run better governments in terms of welfare, industrialization, and infrastructure, and they deserve credit for that. However, linking these achievements to culture may not be wise. Geography is a more convincing explanation.

Venezuela is not being punished. It is being re-made. Not into a liberal democracy. Not into a stable autocracy. Into something more useful. Into a Pakistan. By this, I do not mean a people or a culture. I mean a regime form (as what Bush did to Maduro’s earlier Iraqi doppelgänger): a state kept permanently unstable, permanently securitised, and permanently dependent; yet intact enough to sign contracts, police its population, and function as leverage against rivals. This is the form Empire prefers when it can no longer rule directly.

1) Why Venezuela Matters

Venezuela is not peripheral. It is inconveniently rich.

The largest proven oil reserves in the world (over 300 billion barrels)

Significant natural gas

Large gold reserves

Access to rare earths

Control of the Caribbean–Atlantic corridor, close to major shipping lanes and the US mainland

A sovereign Venezuela is not a local problem. It is a potential pole. This is why it cannot be allowed to work. Donald Trump said the quiet part out loud: Venezuela has “all that oil.” It should be “ours.” The language was crude. The intent was orthodox. What matters is not the tone, but the continuity of aim.

2) Sanctions as a Weapon System Continue reading Venezuela as Pakistan: A Template, Not an Accident

There are places in the world that do not behave the way theory predicts. Chennai is one of them. Tamil Nadu is among India’s richer states. It is urbanised. It is educated. It is globally connected. And yet it retains a form of social cohesion and human reflex that hyper-capitalism usually dissolves.

This is not nostalgia. It is observation.

A Different Social Reflex

In much of the world shaped by late-stage capitalism, interaction is transactional by default. Help is conditional. Suspicion precedes generosity. Risk is individualised. In Chennai, the reflex is still different. People intervene without being asked. Strangers stop when something is wrong. Assistance is offered before motives are assessed. Money is often refused. This is not charity. It is social instinct. That instinct survives even in moments that theory says it should not: late nights, urban settings, infrastructural failure, ambiguity. The absence of alcohol matters. The presence of peer groups matters.

But more than anything, the cultural baseline matters.

Why Tamil Nadu Resists Homogenisation Continue reading Chennai Is Not an Accident

As one does, we were discussing societal rise and collapse on twitter and I said at some point:

User @whatwasthataga4 on X.com (an Indian American) asked: “I don’t understand this once in a millennium opportunity. What exactly is it and how is it supposed to work in the best case?”

I posted an off the cuff reply and wished I could sit down and do a proper post on this. But knowing that I may not get to it, I am just quickly updating my tweet and hoping that commentators will add value.. So here is my “off the top of my head” explanation of this “once in a millenium opportunity” claim.

1. Indian human resources are potentially world class; the wetware is actually OK (though disease and malnutrition do lower IQ in some significant subsets, but cultural strengths compensate as well, so even that is not a lost cause)

2. So, wetware can work. What about software? I think even the software is not entirely corrupted. The bios is still intact for most people (though under threat) and the culture has many elements that make it potentially successful. For example, there is a significant commercial class and tradition, of the South Chinese type, if not equally developed right now. There is also significant respect for teachers and learning (again, not at Confucian levels, but it is very much there) and respect for legal authority (sometimes, maybe a lot of times, too much respect for authority, but there is also a romantic anti-authoritarian assault from Wokish Leftist ideologies that now threatens to over-correct).

You may be getting a hint of why i say its a chance, not a done deal. These are also strengths that are under sustained assault from Postleftist wokish ideologies and in India there is such significant domination of western leftish narratives in the educated classes that there is the possibility they could actually destroy these cultural strengths in another generation. That would be one way to miss the bus. Another would be to start a religious civil war. The second is very high on the list of fears for leftists and liberals, but I suggest we should be equally fearful of too much leftism 🙂

3. The administrative and military machinery of the Raj is intact, vast and relatively modern, and can be redirected to new purposes. I listed this at 3, but this is probably what many people think of when they say “India has a chance, thanks to the Raj”. I think the downsides of colonization exceed any benefits they brought, but no doubt the existence of this apparatus gives India (and even the other successor states of the Raj) an edge over, say, Afghanistan, for better and for worse. Its a mixed blessing but its there, and it CAN potentially be directed to new ends.

4. A vast and successful diaspora (a source of ideas, ideals, money and skills)

5. Relatively good asabiya for such a large country (I dont buy this notion that Indian people in general are not patriotic. If anything, they are excessively and over-sentimentally patriotic . Patriotism matters. (Pakistan has even better asabiya, so this is necessary, but not sufficient 🙂 )

6. The biggest population in the world Demographic dividend. Another obvious point where the opportunity is there now, but wont be there forever.

And so on.. There is a lot more

Add your comments. (I have left the meaning of development vague, but what I personally mean is very conventional success as the first layer (the thought is that this layer itself implies others), so things like being a giant middle income or more economy, with no serious invasion fears and a clearly functional political and economic system that is a very big source of innovation and ideas for the whole planet; I dont mean people will be more virtuous, or a “new man” will be born after the glorious revolution).

BTW, here is a conventional western view of why a chance for very serious development exists in India (at least this was the view last year, relations are more tense now and the strategic directives behind such programs may have shifted)

Postscript: My conspiracy theory is that a thousand conspiracies are launched and some turn out to be workable, but nobody knows in advance that A or B is a sure shot.. It’s a leap into the dark 🙂 (hence, work for the ones you want, when the time is right, it will happen)

Paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ vināśāya ca duṣkṛtām |

Dharma-saṁsthāpanārthāya sambhavāmi yuge yuge

I was recently going through some older posts on Brownpundits i noticed a lot of older commentators who are missing nowadays.

I will just name a few ; if any of you are reading ; please comment

DaThang, thewarlock, Saurav, Bhimrao, Numinous, Ugra, Violet, Santosh etc.

ever since Razib has stopped actively blogging all the Genomics and History Nerds seem to have moved on to Greener pastures