King Khan — I don’t think it’s irrelevant that Muslim-majority regions would have been liminal. Literally.

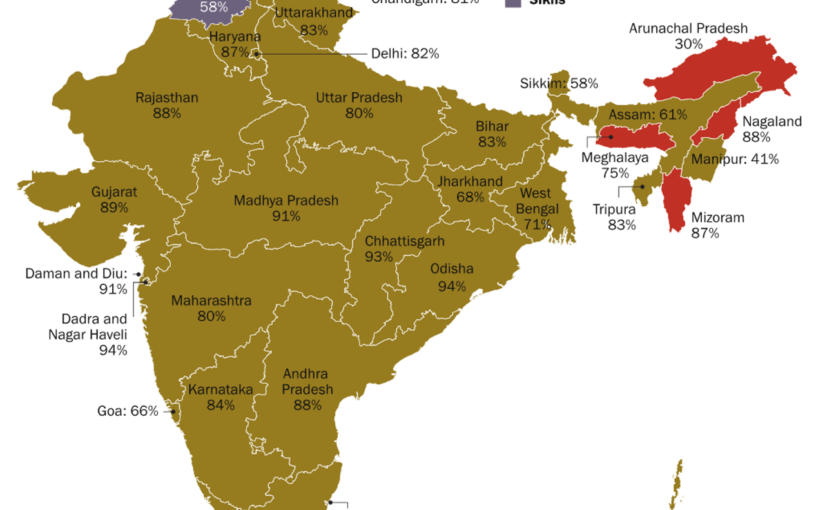

The previous post got me thinking about demographic engineering, and how it has quietly shaped post-Partition India — not just at the borders, but deep inside the Union itself. When Qureishi redefined the demographic weightage of the Indo-Gangetic, I was reminded of how states like Madhya Pradesh (I’ve had a post waiting on this for months), Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar — the so-called “giants” of India’s federal structure — were similarly calibrated. Even the historical Andhra Pradesh (before Telangana split), Kerala, and distant territories like the Lakshadweep Islands show signs of internal rebalancing. The logic? To prevent the consolidation of another Muslim-majority province — something the Indian state has remained deeply wary of since Kashmir’s accession crisis in 1947–48.

The anxiety over Muslim-majority units lies at the core of why Kashmir remains “special” — not spiritually, but politically. Its sovereign ambiguity and constitutional exceptionalism stem directly from the post-Partition plebiscite logic, which India initially welcomed. At the time, Nehru and the Congress were confident of winning that vote. Quaid-e-Azam had thoroughly alienated Sheikh Abdullah, by backing the non-consequential “Muslim Conference” and the National Conference had significantly diverged from the Muslim League. The shift didn’t come until later — particularly after the rigged 1987 elections and the spillover from the Afghan jihad, which together detonated the insurgency.

This raises an unsettling but important question: Continue reading India’s Demographic Nervous System: Partition, Federalism, and the Fear of Muslim Majority Provinces

Let’s unpack Kabir’s comment. Credit where it’s due; his opinions inspire more of my posts. Perhaps it’s time he rejoined as a contributor.

“That may well be true. But you can’t deny that it is the liturgical language of Hinduism. There is zero reason for any Muslim to identify with it (unless they are specifically interested in languages). You could make a case for Pakistanis learning Persian since our high culture is Persianate. The same case cannot be made for Sanskrit.”

If Persian is truly the high culture, then why do ignore the one holiday that defines the Persianate sphere, Norouz? Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Iran, the Kurds, all speak different tongues, yet Norouz unites them. It is the civilizational cornerstone of Persian identity, the cultural “Jan. 1” across centuries of shared memory. But in Pakistan, Norouz is invisible. Not because Pakistan is un-Persian. But because Pakistan is post-colonial. The elite curate rupture, not heritage. Distance, not descent.

And let’s be honest: the erasure didn’t start with the British. Aurangzeb, still lionized by most Pakistanis (his fanaticism and Hinduphobia a plus point), abolished Nowruz as part of his Islamic “reforms,” replacing it with religious festivals. So how can one claim Persianate lineage while revering the very figure who uprooted it?

Continue reading Norouz or Nowhere: The Identity Pakistan Can’t Claim