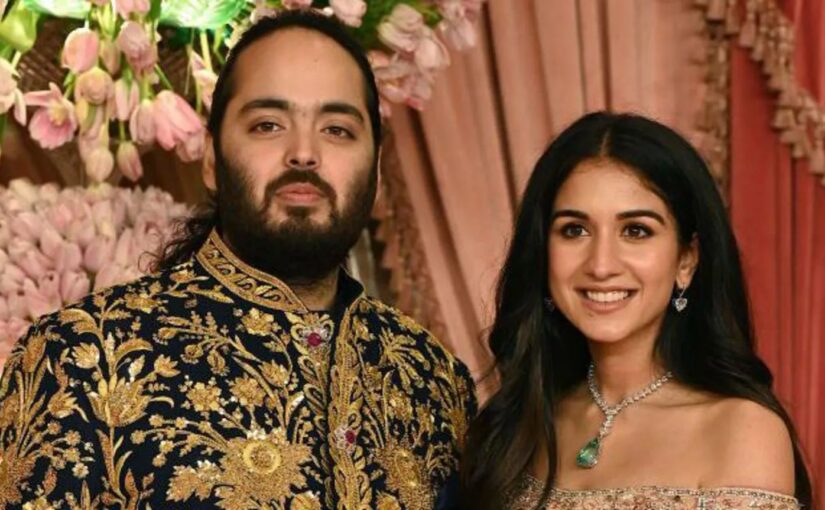

I was speaking with Dr. Lalchand about a number of things, from Anant Ambani’s wildlife project to the recent caste discourse on Brown Pundits. Both, strangely enough, converge around the theme of scrutiny; of who gets to build, who gets to critique, and who sets the rules of engagement.

Let’s start with Vantara. Anant Ambani’s wildlife refuge is coming under sustained criticism. But I ask: why shouldn’t Bharat, arguably the only major civilisation that views animals as divinely inspired, have a world-class zoo or rescue center? If done with sensitivity and vision, this could be a profound expression of India’s Hindu civilisational ethos.

Vantara houses over 200 elephants, 50 bears, 160 tigers, 200 lions, 250 leopards, and 900 crocodiles; albeit imported from across the world into the baking flatlands beside an oil refinery. The scale is staggering. Yes, there are questions: about captive animal welfare, about the case of Pratima the elephant, about transparency. But we should also be able to think of Indian megafauna conservation at global scale especially in a nation where sacred animals are part of dharmic memory.

America had its Gilded Age. The robber barons left behind libraries, parks, and museums. Can’t India do the same? Or do we reflexively dismiss anything built by wealth as vanity? Can there not be a deeper Dharma behind patronage?

And that brings me yet again to caste, controversy, and the structure of Brown Pundits. Continue reading Vantara, Caste, and the Fragile Commons