Last night Dr. Lalchand & I watched Homebound, India’s submission to the Oscars, at Apple Cinemas in Cambridge, Mass. This sad film follows a Dalit (Chandan Kumar) and a Muslim (Mohammed Shoaib Ali) struggling against the odds during the pandemic, their solidarity fictionalized as a fragile bridge across India’s deepest divides.

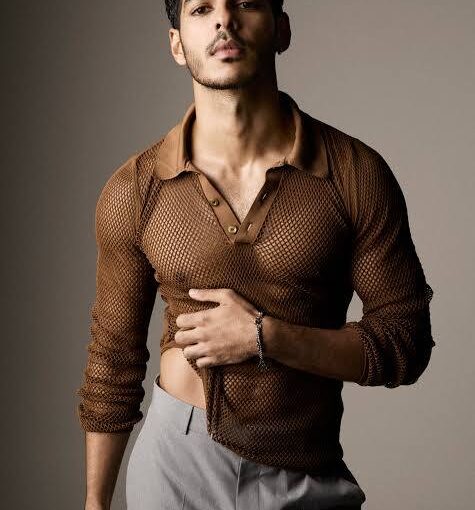

On the surface, it is a familiar story: the disenfranchised facing systemic barriers. But what struck me was how privilege itself performed disenfranchisement. Ishaan Khatter, brother to Shahid Kapoor, plays the marginalized Muslim. Janhvi Kapoor, descended from Bollywood royalty, embodies a Dalit woman. Vishal Jethwa, a bright-eyed Gujarati, portrays the Bhojpuri Dalit lead. This is not unique to India; Hollywood, too, casts elites as workers. Yet it raises the question: when poverty is performed rather than lived, is it “Dalit-washing”?

Poverty, Emotion, and Representation

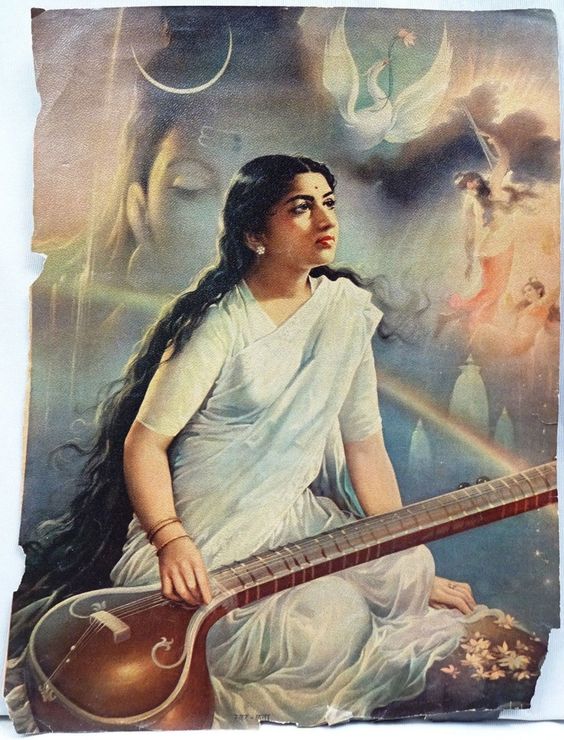

Watching the film, I reflected on poverty’s emotional landscape. For elites, emotions can be expansive, indulgent, aestheticized into art. For the working poor, emotions are often constrained by survival — narrowed into necessity. Homebound tried to humanize its characters, but I wondered whether it romanticized what in practice is a relentless narrowing of possibility.

The West rewards this narrative. Parasite in Korea, Iranian cinema, Slumdog Millionaire — poverty & Global South tribulations as spectacle becomes “poverty porn.” The Guardian gave Homebound four stars. Great art often tilts melancholic, yes, but here the melancholia is curated for Western consumption.

Identity, Vectors, and Islamicate Selfhood

More unexpectedly, the film stirred something personal. I realized how much I have vacated my own Islamic identity. It was not traumatic. As a Bahá’í with Persian cultural roots, I found overlap — even comfort — in Hindu traditions. Dalits, in their rapid Hinduization, represent one vector of assimilation; Muslims and scheduled-caste Muslims, often in tension, another. Homebound imagines solidarity, but in life these vectors pull unequally. Continue reading Homebound with Ishaan Khatter