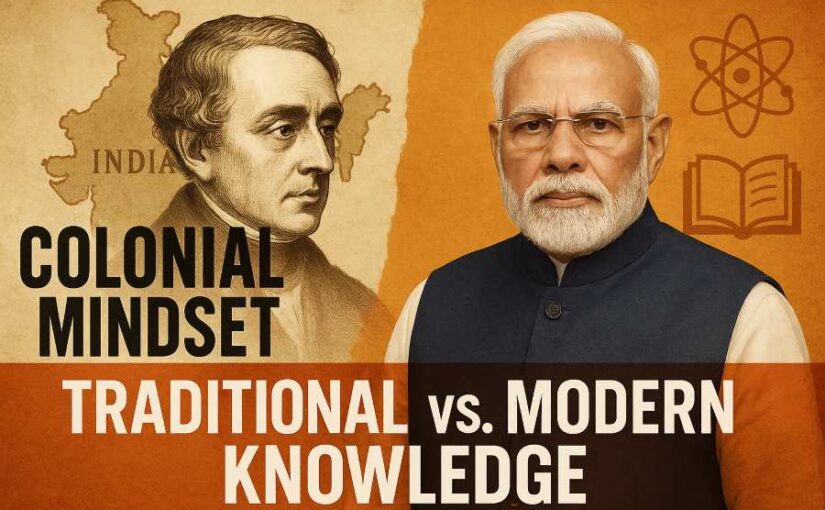

We had some discussion about Macaulay on X and I wanted to write a piece about it, but I also know I probably wont get the time soon, so I am going to just copy and paste the discussion here, I am sure people can follow what is going on and offer their comments.. (Modi’s speech link at end, macaulay minute text link as well)

It started with this tweet from Wall Street Journal columnist Sadanand Dhume:

In India, critics of the 19th century statesman Thomas Macaulay portray him as some kind of cartoon villain out to destroy India. In reality, he was a brilliant man who wished Indians well. Link to article.

I replied:

I have to disagree a bit with sadanand here bcz I think while cartoonish propaganda can indeed be cartoonish and juvenile, there is a real case to be made against the impact of Macaulay on India.. Education in local languages with hindustami or even English (or for that matter, sanskrit or Persian, as they had been in the past during pre islamicate-colonization India and islamicate India respectively) as lingua franca would have been far superior, and the man really did have extremely dismissive and prejudiced views, the fact that they were common views in his world explains it but does not excuse it. The very fact that many liberal, intelligent and erudite Indians of today think he was “overall a good thing” is itself an indication that his work has done harm.. BTW, there were englishmen in India then who argued against Macaulay on exactly these lines..

Akshay Saseendran (@Island_Thought) replied: Continue reading Macaulay, Macaulayputras, and their discontents