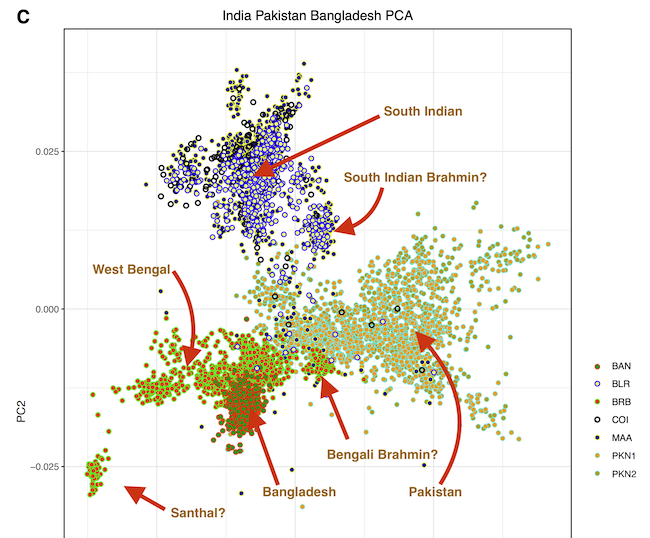

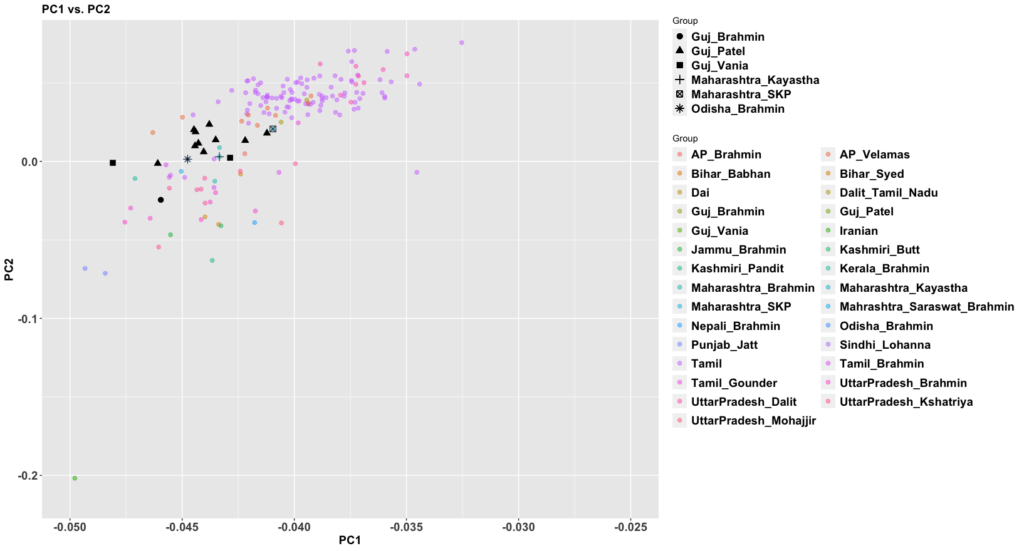

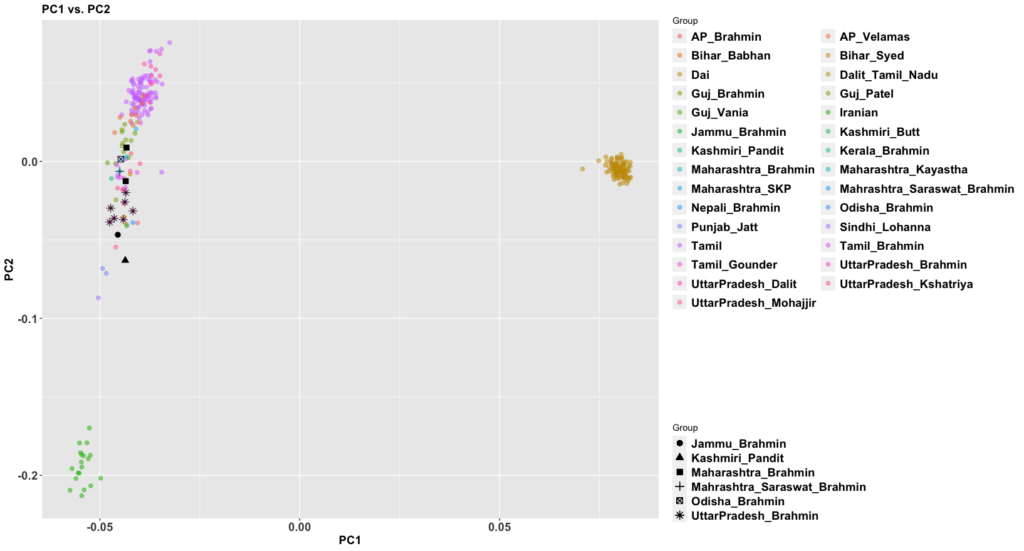

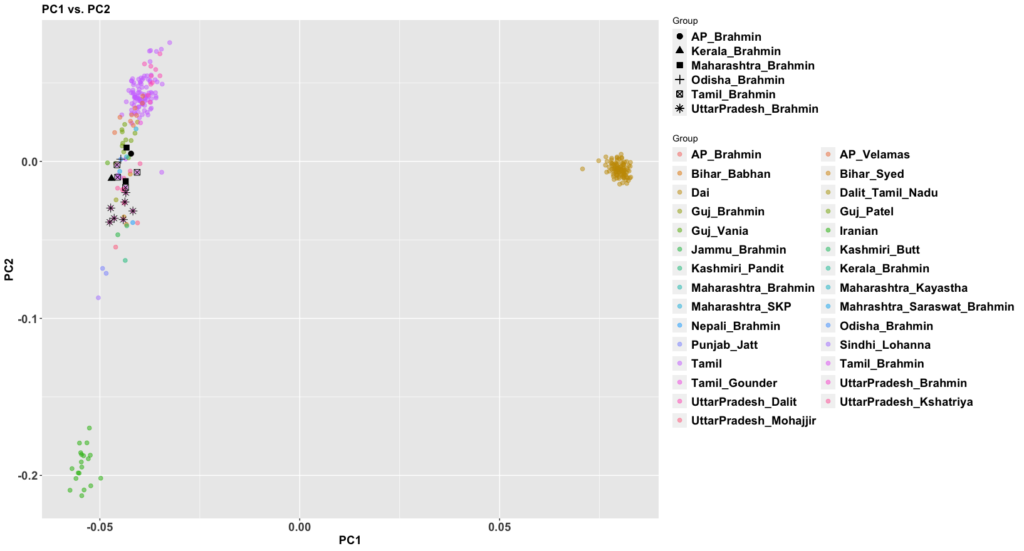

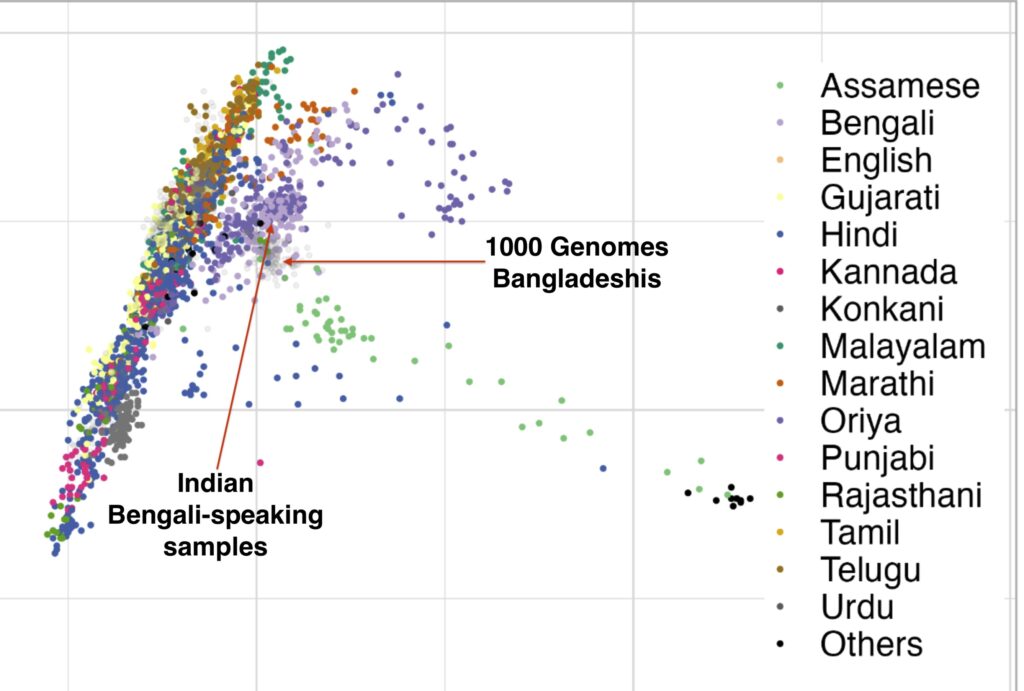

The new paper, 50,000 years of Evolutionary History of India: Insights from ~2,700 Whole Genome Sequences, is very good. It also answers a question that comes up sometimes: how different are West Bengalis from Bangladeshis? We haven’t had a apples to apples comparison until this paper that’s easy to understand.

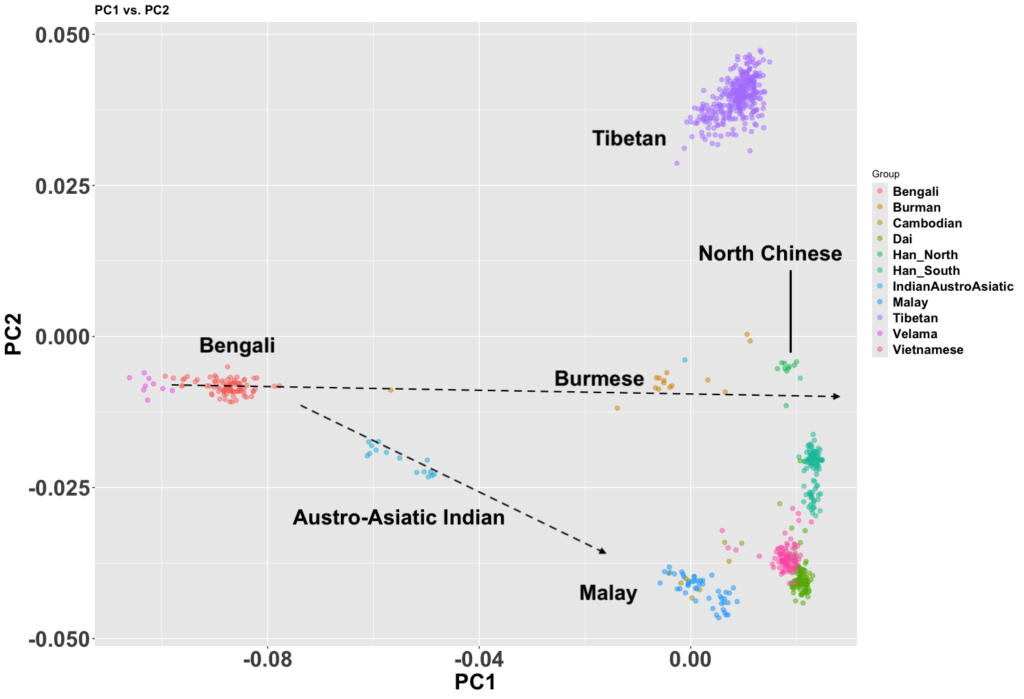

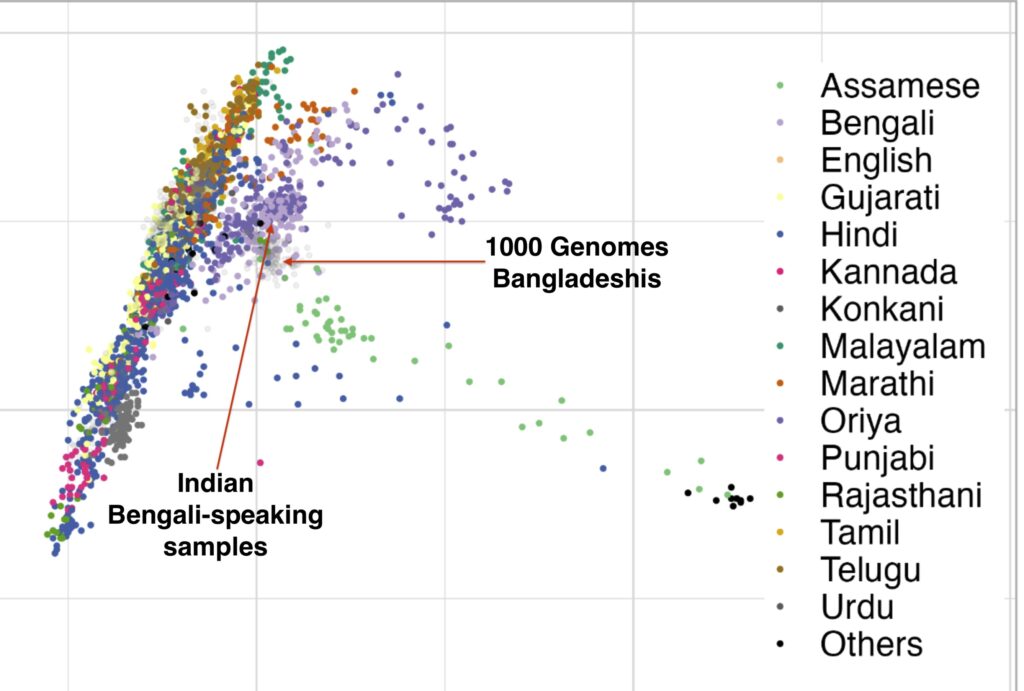

There are figures in the paper that make the overlap clearer. The main difference is more variance in the West Bengalis, and a greater East Asian shift among Bangladeshis. But the latter is clearly just geography; those whose ancestry is from the east of the Padma (like me) always have more East Asian ancestry than those from the west, while those in the north also seem to have more.

The variance in West Bengal is probably driven by caste. You can see Brahmins, and probably what are Bengali-speaking scheduled castes and tribes. In the Bangladesh Muslim population everyone eventually intermarried.

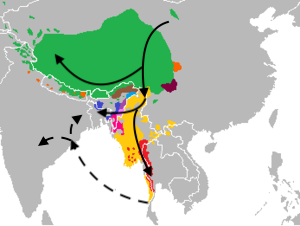

The Assamese are even more East Asian shifted than the Bangaldeshis. As I said in a previous post, these Indo-Aryan groups look like they mixed with a Khasi-like population at some point.

Finally, the West Bengal population had admixture from an East Asian group between 500 and 600 AD. This is the same date as for the Bangladeshis, meaning they are both the same population with the same origin. The major difference seems likely to be the proportion of East Asian ancestry and lack of caste structure within eastern Bengal.