The following post is contributed by @saiarav from X or Yajnavalkya from Medium

The 1946 vote and the Muslim mandate for partition

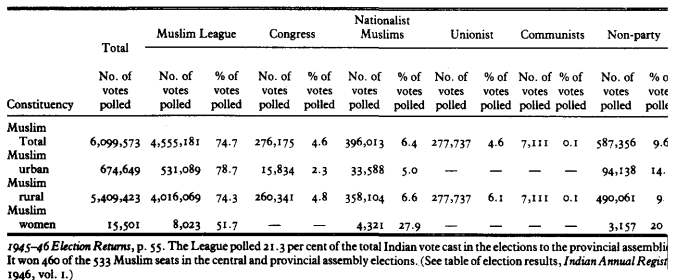

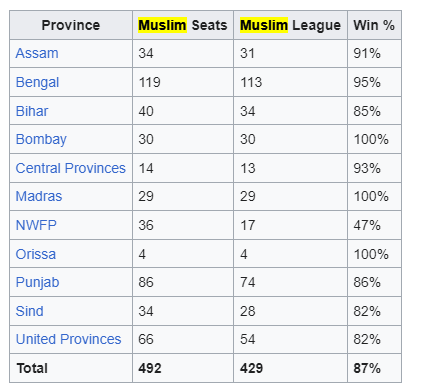

The 1946 elections remains inarguably the most consequential election within the Indian Subcontinent. Jinnah’s Muslim League (ML)went into the polls with a single-point agenda of partition and the Muslim voters responded with feverish enthusiasm, delivering a crushing victory for ML across all provinces, thereby paving the way for partition. The party won an overwhelming 75% of the Muslim votes and 87% of the Muslim seats, and except for NWFP, its minimum seat share was 82% (see table below). Of note, provinces from current day India -places like Bombay and Madras, which had zero chance of being part of a future Pakistan – gave a 100% mandate to Jinnah.

(for those who are not aware, we had a communal electorate at that time which meant Muslim voters would vote exclusively for Muslim seats)

Facts belie claims of Muslim society non-representation in mandate

As regarding the role (culpability?) of the Indian Muslim society in facilitating partition, establishment historians put forth two arguments. One, Jinnah had kept the Pakistan promise deliberately vague and hence the voters did not realise what they were voting for. Two, the overwhelming mandate from the voters cannot be taken as representative of the sentiments the whole society as only a tiny proportion of Muslims had the right to vote. The first one is a qualitative debate and can be debated endlessly. But the second assertion is easier to examine since we have actual voting and demographic data and that is what I will endeavour to do in this post. I reference one specific claim which is quite popular in social media — that the mandate was only from 14% Muslim adult population, based on an article written by a leading X handle, Rupa Subramanya, who has a rather interesting history with respect to her ideological leanings.

The analysis that follow will show that at least one adult member (mostly male) from close to 40% of the Muslim households in British Indian provinces and at least 25% of Muslim adults were eligible to vote .

I cannot emphasize enough that this is not something which should be used to question Indian Muslims of today. The founding fathers of the modern Indian nation made a solemn promise to Muslims that they will be equal citizens of this nation and that should be unconditionally honoured. But as a society, we should have the courage and honesty to acknowledge historical facts rather than seek to build communal peace on a foundation of lies, as the left historians have done; Noble intentions are not an excuse. Talking of fake history, one cannot but marvel at the sheer degree of control over the narrative of the establishment historians that they have managed to perpetrate the claim about the 1946 vote for more than seven decades when there is hard quantitative data available on number of voters, the country’s adult population etc. One can only imagine the kind of distortions they would have done to medieval history where obfuscation would have been infinitely easier.

Some basic facts about the 1946 elections

I will start off with some facts and estimates which are broadly indisputable.

A) The 1946 provincial elections was limited only to British Indian provinces

The 1946 elections was limited to provinces directly ruled by the British which accounted for roughly 3/4 of British India’s population. While the provincial representatives in turn elected 296 members of the Constituent Assembly, the princely states nominated 93 members the constituent assembly, i.e in proportion to their respective population. With ML bagging 73 of the 78 Muslim seats in CA, the partition debate was as good as sealed.

B) 28% of the adult population of the provinces was eligible to vote

The total strength of the electorate was 41.1 million voters while the total population of Indian provinces was 299 million. Taking into account only the adult population (age of 20+, ~50% of the population), it implied 28% of the population were eligible to vote.

(data is sourced from Kuwajima, Sho, Muslims, Nationalism and the Partition: 1946 Provincial Elections in India, Manohar, New Delhi, 1998, p. 47.)

C) An estimated 25% of the adult Muslim population of the provinces were eligible to vote

While I am unable to source the actual data for the percent of eligible voters within Muslim community, there is no reason to think it would be an order of magnitude lower than the overall 28% number. As I show in the Appendix, voter and turnout data indicates the number should be in the 25% range, if not higher; i.e. about 9 million Muslims out of 37 million adult Muslim population in the provinces were enfranchised.

D) Close to 40% of Muslim households had members eligible to vote

The 28%/25% voter ratio discussed above is skewed by the fact that very few women were allowed to vote. Only 9% of adult females had voting rights which in turn implied that 46% of adult males had voting rights. (Source: Kuwajima, Sho). If we assume the same proportion for Muslim females, that would imply little over 40% of Muslim adult males were enfranchised.

E) 75% of the 6 million Muslim votes went to ML

4.5 million Muslims voted for Muslim League out of a total 6 million Muslim votes cast from an electorate size of 9.2 million. Of note, there is no major urban-rural divide — the figure for rural areas is 74% vs 79% for urban areas.

Muslim mandate way more broadbased than projected in mainstream narrative

Based on the above data, at the very least, one has to concede that 25% of the Muslim society had a say on the issue of Pakistan and three-quarters of that group did vote for creation of an independent Muslim State. This severely undercuts the claim that only a tiny elite voted for Pakistan — Rupa’s 14% figure, for example, is clearly wrong **. But even the argument that the bottom 75% had no say on the issue is inaccurate because the voting rights were not just based on class, but also on gender. As noted above, close to 40% of adult male Muslims were enfranchised — in other words, 40% of Muslim households had an adult member who could vote. And of this 40%, three-fourths or 30% chose to vote for Pakistan. That clearly means that a much larger cross-section of the Muslim society had a say than just a tiny elite or the educated middle classes (or the salariat class as Ayesha Jalal calls it). This appears to be a more reasonable interpretation of a mandate given the context of the time when universal for women was still a new or evolving concept in many advanced democracies.

** The error that Rupa makes in arriving at the 14% figure is two-fold. One, she takes the adult Muslim population for entire British India (~44 million) whereas the elections were held only for provinces (~37 million). Second, she uses actual voter turnout (6 million) instead of the total size of the Muslim electorate (~9.2 million).

What are some of the counterarguments to the above interpretation?

A) What about the fact that the Muslims in princely states had no vote?

This argument, on the face of it, is not without merit. But one needs to be honest about framing it — this is not a case of a vertical class divide in enfranchisement but a horizontal regional divide. Therefore, the proponents of the non-representative nature of the mandate will have to make the case that the Muslim subjects of the princely states would have taken a significantly different view on Pakistan versus the ones in the provinces, just harping on the class divide will just not cut it.

Let us look at what the data can tell us. The adult Muslim population from the princely states would be another 8 million. Based on 1941 census data nearly 60% would be from three large states — Hyderabad (17%), Punjab (18%) and Kashmir (24%). Is there any reason to believe that the Muslims of Hyderabad or Punjab would have voted very differently versus their neighbor provinces of Madras Presidency or Punjab province? A debate on this issue is beyond the scope of this post but I would say that the burden is on those making the “non-representative mandate” argument to make that case.

For the record, if we take total Muslim population figure, then the proportion of adult and male adult enfranchisement of Muslim community would go down to 21% and 34% respectively

B) Muslim women were largely excluded

As noted earlier only about 9% of adult women were enfranchised. Assuming a similar (or lower) figure for Muslim women, indeed they had little say on the matter. One interesting aspect is that even among the Muslim women eligible to vote, very few seem to have turned up to vote. Only 15K of them voted which would be a turnout in the low single digits at best! But among those who did vote, more than 50% voted for ML, which is admittedly well below the overall support of 75%. But still, the fact is that a slim majority of Muslim women too voted for Pakistan. Also, electoral mandates need to be interpreted based on the context of that time and broadbased women suffrage was still at a relatively early stage even in more advanced democracies.

C) Hey! only 4.5 million out 37 million Muslim adults voted for ML

This would mean only 12% of adult Muslims expressed support for Pakistan. In a very narrow mathematical sense, this is, of course. right. But this is just not how electoral mandates are interpreted in any democracy. If one uses this yardstick, it would mean Presidents in one of the world’s oldest democracies, have been consistently elected with support of just a quarter of the electorate because voter turnout in US has generally been around 50%. The ones who had the right to vote but chose not to exercise it will need to be excluded from any interpretation of the mandate.

Conclusion — acknowledge history and move on

Partition has a cast a long shadow on Hindu-Muslim relationship and perhaps it was a wise decision in the immediate aftermath to underplay the Indian Muslim community’s role in it. But a fiction cannot be the basis for a permanent peace. At some point, we will all have to collectively acknowledge the historical facts and have the maturity to move on. One additional problem also is that this fictional narrative about the mandate further feeds into the Muslim victimhood that they had chosen a secular India over a Islamic Pakistan and have been betrayed by rising Hindu majoritarianism. A honest appraisal of history might perhaps lead to a more constructive political strategy.

Appendix — estimate of eligible voter percent within Muslim community

A) The Muslim population in the provinces was 79.4 million. Given higher birth rate among Muslims, the adult population is lower than the national average — using Pakistan’s 1951 census data as a proxy, I estimate the adult Muslim population to be 47% or 37 million.

B) Total number of Muslim votes cast was 6 million (Ayesha Jalal)

C) Average turnout across communities was around 65%

D) If one assumes a similar turnout for Muslims, then the total electoral size for Muslims comes to 9.2 million which implies 25% of adult Muslim population was eligible to vote. It is quite likely that the turnout was much lower because the turnout amongst Muslim women was abysmally low (Ayesha Jalal)

So it is reasonable to conclude that at least 25% of the adult Muslim population living in the provinces were enfranchised in 1946.