TW: This post contains descriptions of suicide.

Guru Dutt’s 1957 classic Pyaasa is about a disillusioned poet who is aghast at how people treat fellow humans in their pursuit of wealth, lust and power. In the iconic ending monologue, Dutt clarifies that he has no complaints against his friends, brothers and all the others who ill-treated him. His problem is with the structure of society, which peels away the humanity from humans.

19-year-old Abraham Biggs from Florida, USA was a regular on messaging board BodyBuilding.com. Apart from threads dedicated to diet, exercise, powerlifting, etc., there was a miscellaneous section on the site for random discussions not particularly related to bodybuilding. Predictably, this became the light-hearted section of the site- memes, jokes and banter flowed freely.

At 2:35 AM on November 19, 2008, Biggs posted a thread- he was going to commit suicide while livestreaming on Justin.tv, a streaming site and a precursor to Twitch. This was not the first time Biggs was talking about his mental health – he had started another thread in December 2007 about feeling down and how he had attempted to take his life earlier.

Biggs had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and had been taking prescription medication for it. His plan was to overdose on the meds.

Disgustingly, the comments on his stream were goading him on, or calling the whole thing a hoax.

A 17-year-old regular of the site (username: “Bulker”) chanced upon the thread, and clicked through to the livestream. Bulker was alarmed to see what was happening. He had interacted with Abraham on the site before, and felt compelled to act. The problem was, he was at the other end of the world- in India. He did some quick online sleuthing and found Abraham’s name, number, approximate address and pictures. He posted these details, and even updated Miami police contact details on the thread, begging US folks to do something. But no one did.

This was the bystander effect at play. Like people gawk at traffic accidents but don’t do anything about it if there are other people around. They just assume that someone from the crowd must’ve already taken action, like alerting the authorities. This effect was first identified in the murder of Kitty Genovese.

Bulker realised no one was going to act. He tried emailing Miami police but the mail bounced. He snuck into his parents’ bedroom and accessed his mother’s phone. After activating the exorbitantly expensive international calling plan, he called Miami police and tried to explain the situation. He kept getting transferred around and he had to explain over and over again. The clock was ticking, his calling minutes were running out and he couldn’t make any headway, except to locate Abraham’s exact jurisdiction and which sheriff to contact. He posted this information too on the forum. Someone finally realised the seriousness of the matter, and called the sheriff. Minutes later, Bulker too got in touch with him- he had now activated international minutes on his father’s phone. The sheriff reassured him that they had already received multiple calls and help was on the way.

Police arrived at the scene about 15 minutes later. It was 3 PM in Florida and 1:30 AM in India. On the livestream, they were first seen throwing something towards Abraham, and when he didn’t respond, they entered the room, checked his body and then covered the camera. Abraham Biggs had already passed.

This incident affected Bulker deeply. He got involved in social work, first in Gujarat and then Bengaluru, where he moved to in 2016. He volunteered during the COVID pandemic, and was able to get acquainted with the city police commissioner, who encouraged him to get more involved in public issues and act as an interface with authorities.

And thus we arrive at December 11, 2021. Bulker, whose real name is Dushyant Dubey, started a new thread on the r/bangalore subreddit:

Bangaluru is a city in flux, with a large number of young people moving here to work at the IT companies and startups that make it India’s Silicon Valley. Many of these kids are away from home for the first time, and do not have a local “contact” that protects their interests from landlords, PG owners, cops, rowdies (slang for street thugs), MLA’s, <insert goon group here>. An immigrant himself, Dubey understood these problems intimately.

He offered to be of help, to anyone and for anything. The requests started coming in, small and big, with many users tagging him in relevant threads using his delightfully named handle – u/St_Broseph.

Someone needed help filing a police complaint. Another user needed therapy but couldn’t afford it. Broseph happily paid out of his own pocket. One young woman had been sexually harassed by a policeman, and broseph helped escalate the issue and make sure the complaint was registered and acted upon. He even maintains a safehouse for people in distressed situations.

Between representing common folks in disputes with politicians, and (I kid you not) rescuing kittens, broseph has done it all. Following the suicide of Aditya Prabhu, he organised a protest to spur the investigation and formed a student support group. The r/bangalore community loves him- many people volunteer time and money towards his efforts. They call themselves the St.Broseph Army, and have a HQ and everything.

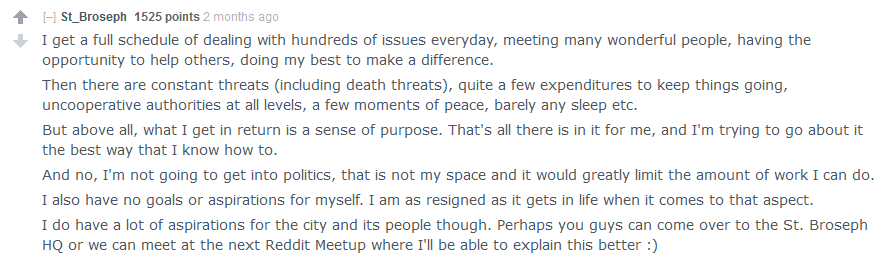

What’s next for broseph? In his own words:

Here’s a toast to Bengaluru’s Batman: not the hero we deserve, but definitely the one we need right now.

I’ll end with a quote by Mr. Rogers:

Note: This post originally appeared on Internet Stuff.

In my view a level 5 PISA score is the minimum requirement for a person to be considered a high school graduate who is literate in math, able to function in the modern global economy, or be qualified to attend college. The PISA report defines a level 5 PISA score or better as a fifteen year old that “can model complex situations mathematically, and can select, compare and evaluate appropriate problem-solving strategies for dealing with them.”

In my view a level 5 PISA score is the minimum requirement for a person to be considered a high school graduate who is literate in math, able to function in the modern global economy, or be qualified to attend college. The PISA report defines a level 5 PISA score or better as a fifteen year old that “can model complex situations mathematically, and can select, compare and evaluate appropriate problem-solving strategies for dealing with them.”