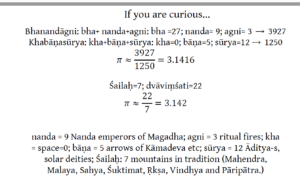

Introduction

A common claim that can be increasingly found in the Indic internet is that the steppe ancestry found in modern day Indians with significant frequency entered India in the late Iron Age and/or the Early Historic Period. Dr Niraj Rai has implied as much in interviews, and Ashish has championed this theory, recently identifying a sample in Iron Age Turkmenistan as an example source of ancestry for modern day Indians.

I previously responded to these claims on Twitter and am here restating my arguments together with some additional analyses. To begin with, we must understand the geography of gene flow from the steppe, whether via migrations or via inter-marriages.

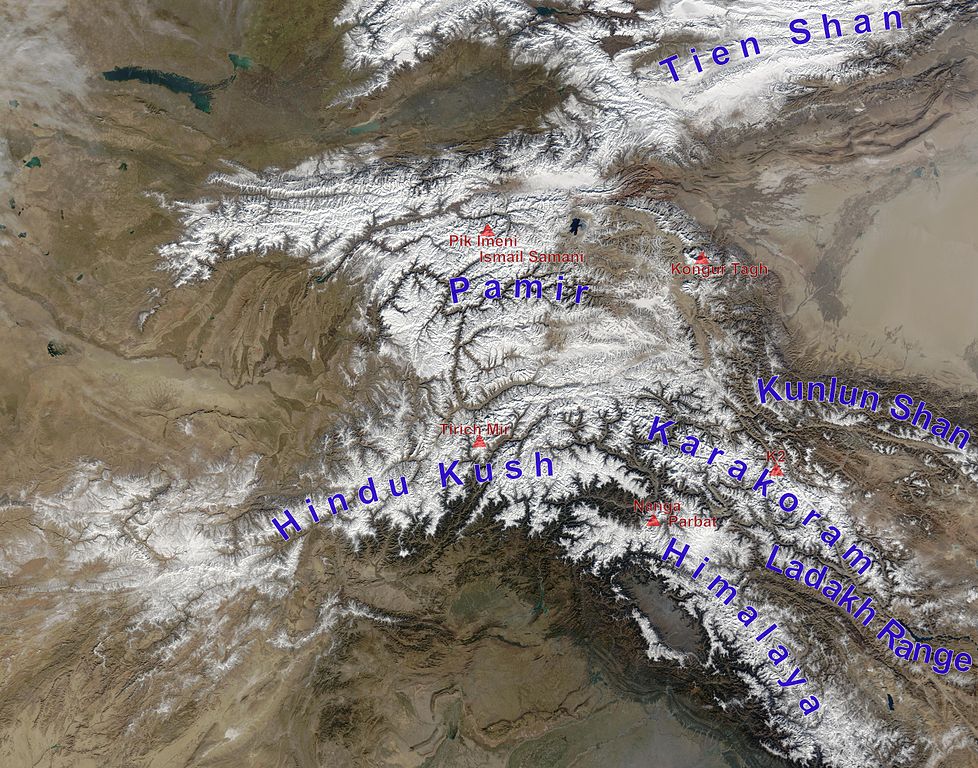

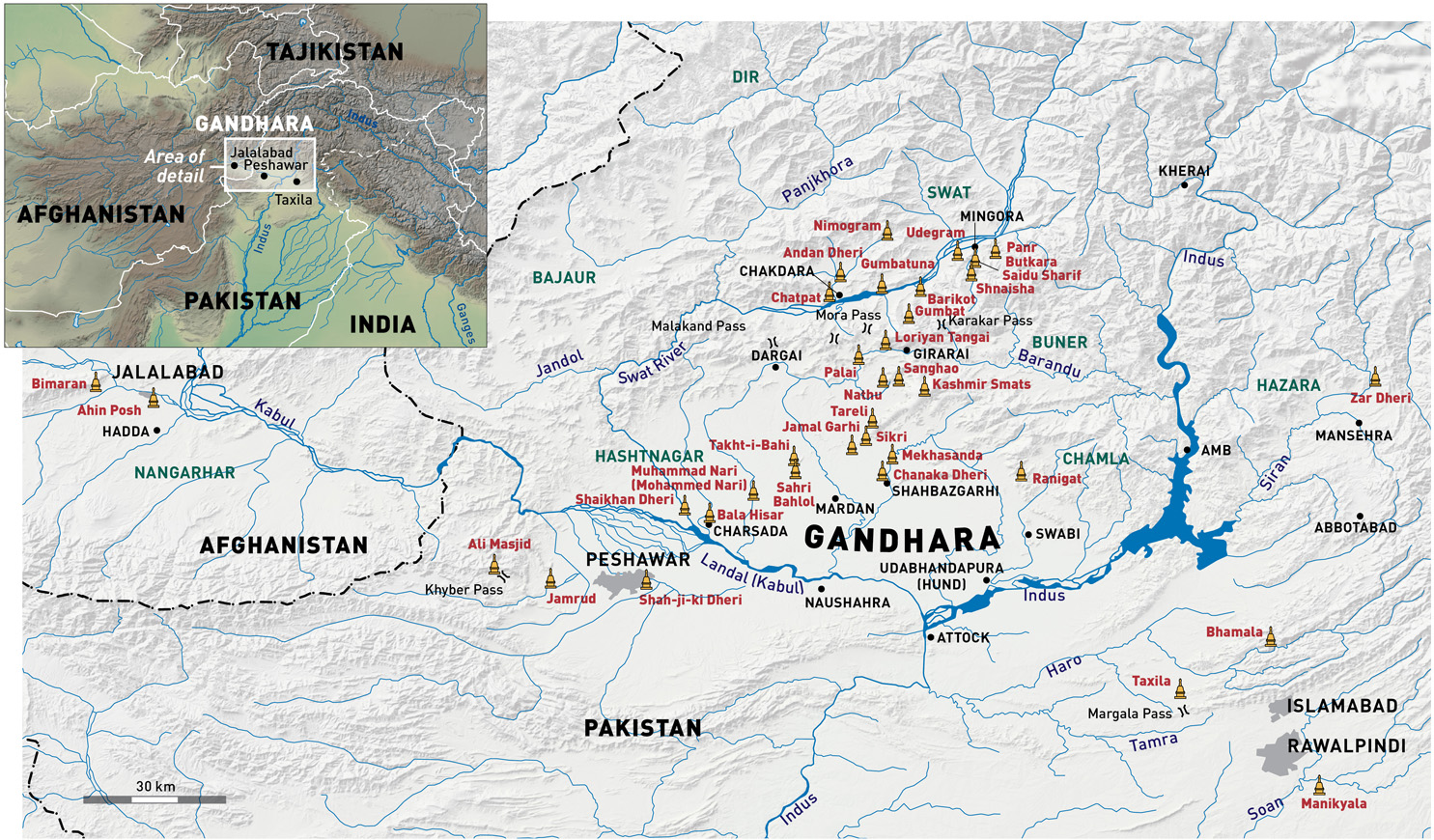

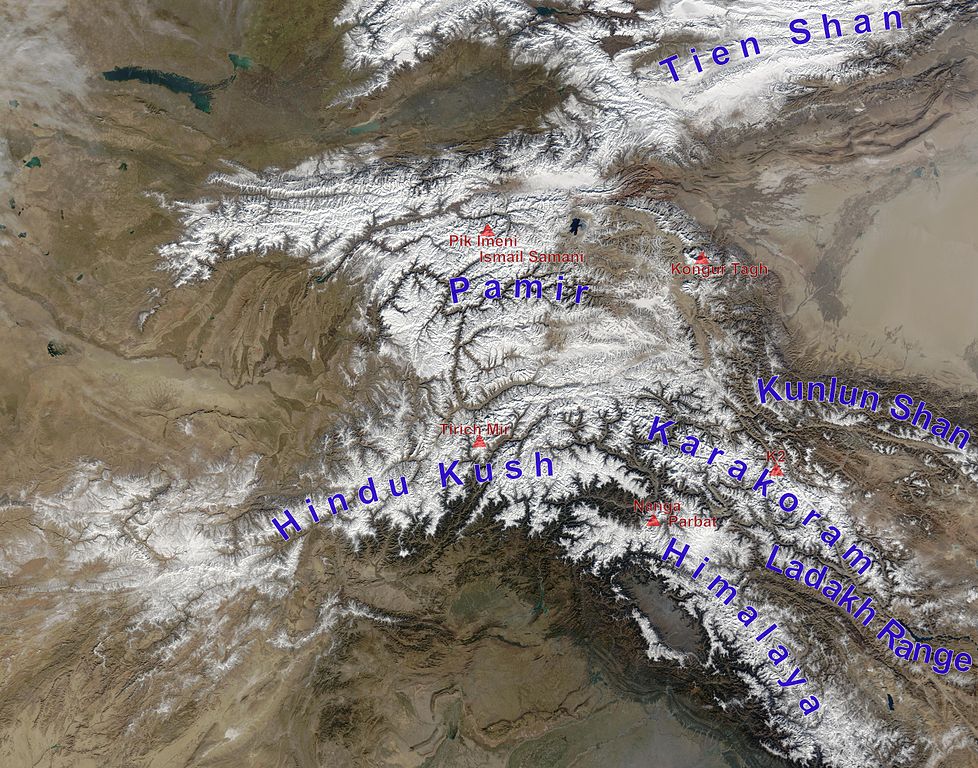

Geography of migrations

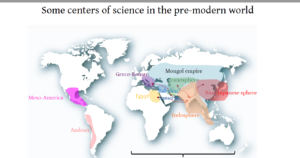

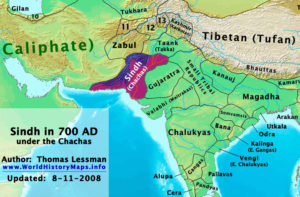

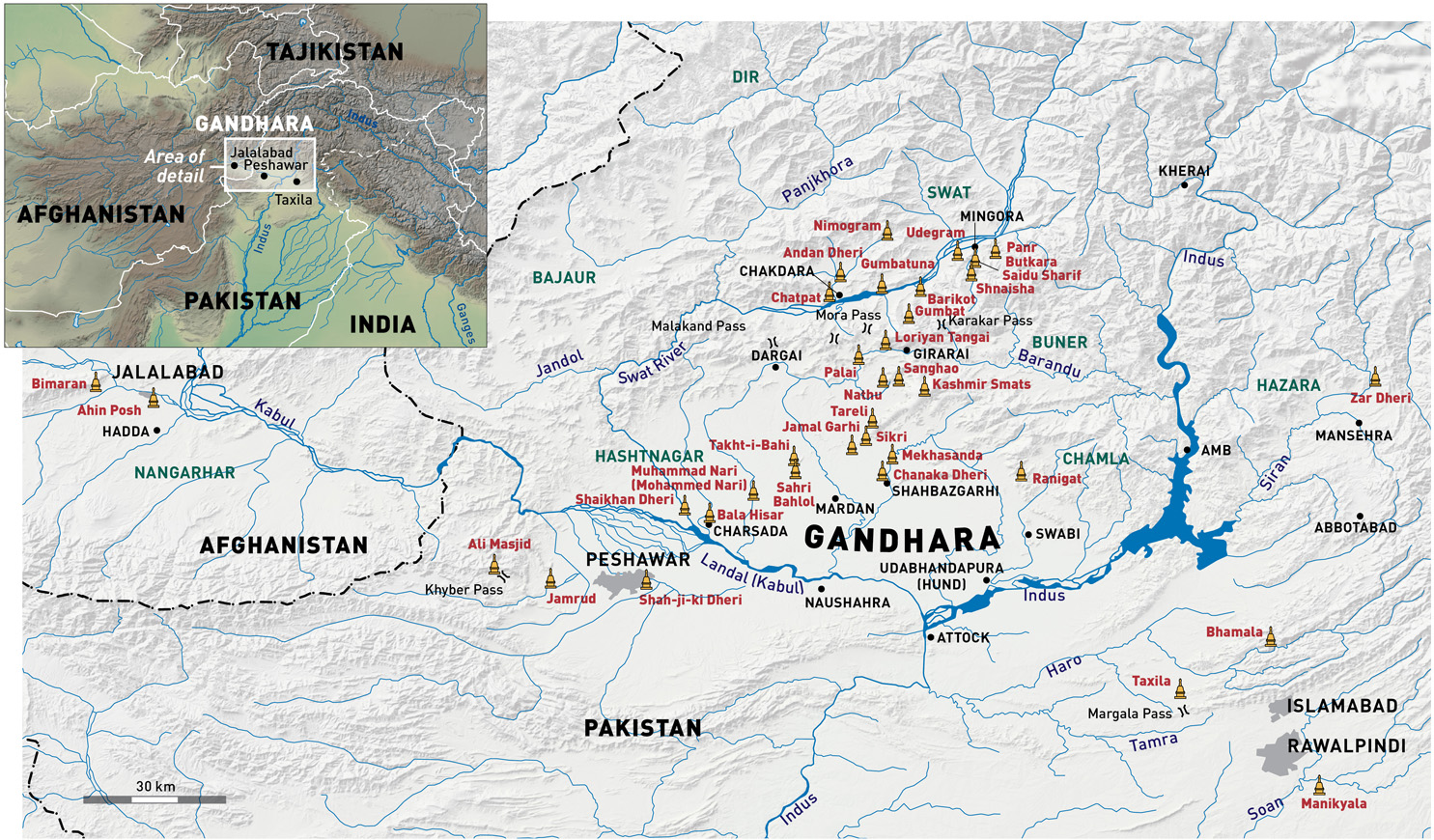

Here are some maps of the northern end of the Indian subcontinent. Notably, the Hindu Kush mountains formed a barrier between Gandhara and the areas north of it – travel through this area in large numbers was quite difficult. Instead, travelers from the steppe would travel around the western tip of the Hindu Kush mountains, heading southeast from Balkh to Kabul/Begram through semi-mountainous lands, and from there heading east down the Kabul river valley into the Vale of Peshawar via the Khyber Pass, to the city of Pushkalavati at the Bala Hisar / Charsada sites. From there, they could head down the Indus Valley or more commonly further east to Taxila, before continuing on towards the Ganga Valley. An alternate route would travel around the semi-mountain regions of Afghanistan, heading south from Herat to Kandahar, and then southeast from there via the Bolan Pass into the middle of the Indus Valley (i.e. roughly the Punjab-Sindh border).

Either way, the Swat Valley in the mountains north of Gandhara was not a stopping point along the route into India. Furthermore, the Swat Valley was not directly part of the general Indian geographic sphere, which extended up to about Shahbazgarhi. In many ways Swat’s relationship to the Indus Valley was akin to Nepal’s relationship to the Ganga Valley – significant trade and cultural contact but also some degree of genetic differentiation.

As such, we would expect steppe ancestry to have entered in greater proportions into Indo-Gangetic Plains than in Swat – especially into Punjab. In fact, that’s exactly what we observe in modern populations. The highest steppe ancestry modern populations are Punjabi / Haryanvi Rors and Jats.

To ascertain the timing of steppe admixture, ideally we’d have ancient DNA samples from the relevant time periods in these regions to check directly for steppe admixture. However, due to a mixture of climate issues, underfunded archeology, and a culture of cremation, there is a total dearth of relevant ancient DNA samples. Instead, we must rely on what samples we’re able to find and utilize the DATES tool to estimate admixture times.

DATES Estimates

Interpreting / theory

Now, to interpret DATES results, we must keep in mind particularly with an incompletely admixed population such as India’s, that admixture times can be much later than migration times. When Indian-residing groups with elevated steppe ancestry interbreed with those with low steppe ancestry, their intermediate steppe ancestry offspring will show more recent admixture. This does not mean the steppe migration occurred at the time of admixture, but rather that admixture continued after migration occurred. As such, admixture times are lower bounds, not mean estimates, for the timing of migration. In the Indian context, we must look to older samples as well as groups with early caste endogamy to discern the true time of migration, without the confounding effects of later intermingling.

Additionally, when modeling with DATES, preference should be given to the model that provides the narrowest estimates. Per Chintalapati et. al., a model is considered to be valid if the Z-score is > 2, the normalized root mean square deviation is below 0.7, and estimated number of generations is below 200.

To model the sources of admixture in DATES, I’ve used Sintashta-Petrovka samples for the steppe source (both sets of Sintashta samples as well as the Petrovka sample available in the Reich database) against the AASI-proxy used by Narasimhan et. al. (STU.SG, ITU.SG, BIR.SG) plus Irula.DG and Pallan-like Roopkund outliers. Using the relatively pure Sintashta-Petrovka samples instead of Central_Steppe_MLBA particularly reduces the noisiness of DATES modeling in the single target sample modeled later here.

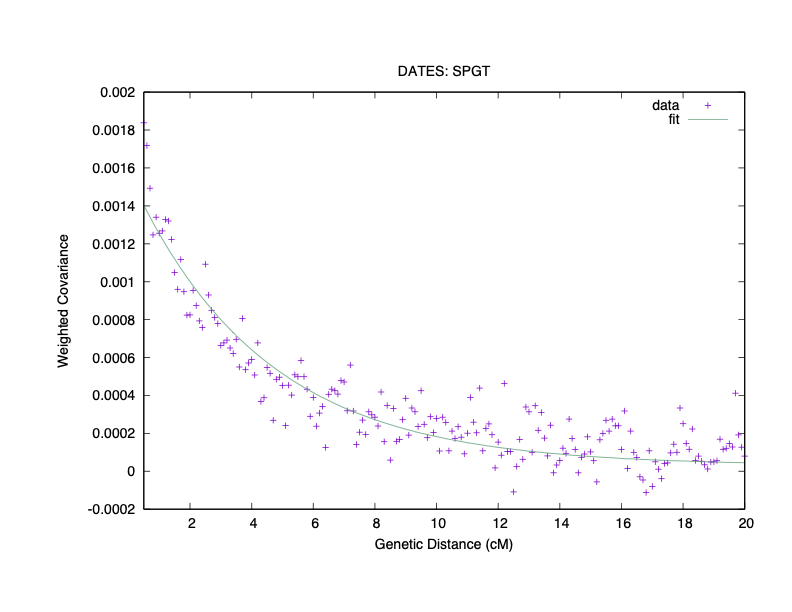

We can sanity check this model by testing admixture times for steppe-enriched Iron Age Swat samples and ensure the results are calibrated in line with the Narasimhan paper:

mean: 27.970 std error: 2.691 Z: 10.394

nrmsd: 0.055

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1853-1552 BCE

This yields a good fit that’s pretty much identical to the Narasimhan paper and indicates that steppe ancestry entered the Swat Valley in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE.

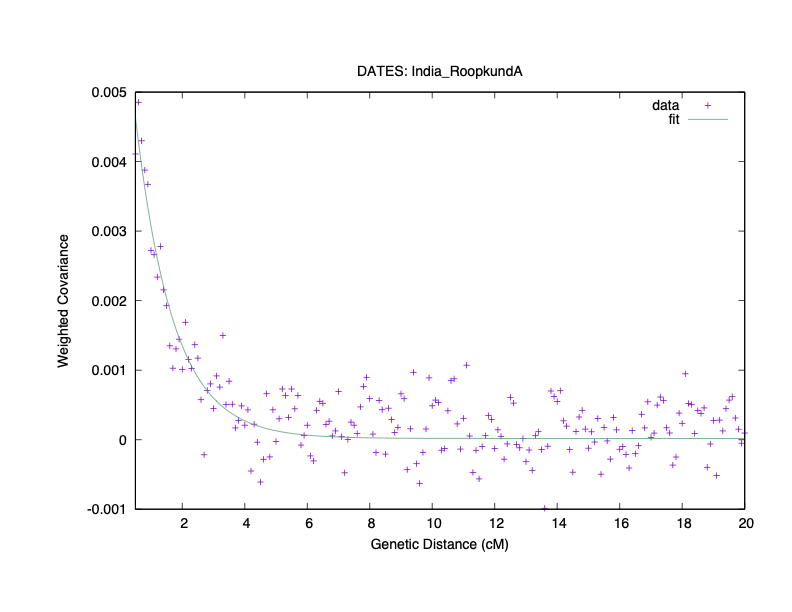

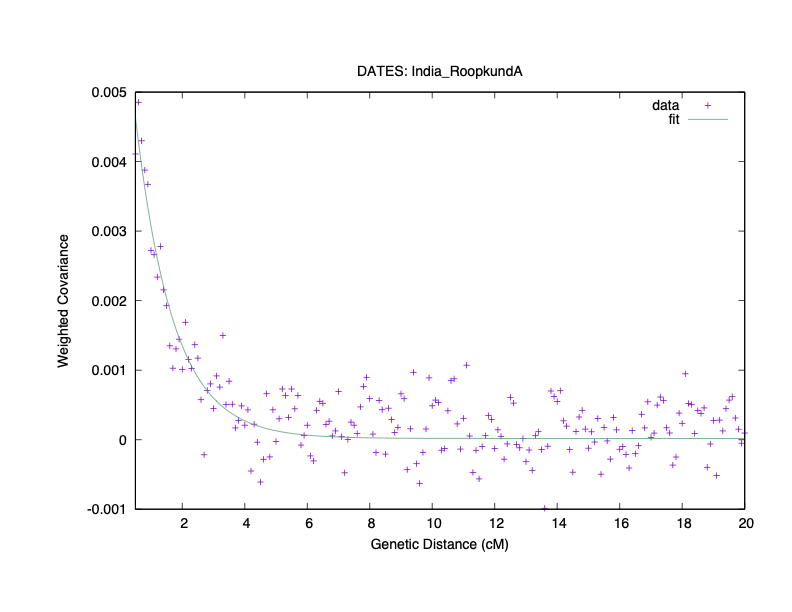

In Roopkund

To find a bound on the timing of admixture in mainland India, we can examine one of the few sets of premodern DNA samples – namely, a collection of pilgrims who had succumbed to hailstorms in the 8th-10th centuries CE in Roopkund Lake. The skeletons sequenced here had a variety of steppe ancestry and included several individuals with relatively high steppe ancestry who clustered with modern day Brahmin Tiwaris.

mean: 84.592 std error: 10.206 Z: 8.288

nrmsd: 0.100

Sample date estimate: 850 CE

95% interval admixture estimate: 2091-948 BCE

The fit is excellent and the results are highly statistically significant. We see clear evidence that the Roopkund samples obtained their steppe admixture in the 2nd millennium BCE and became relatively genetically isolated by the start of the 1st millennium BCE.

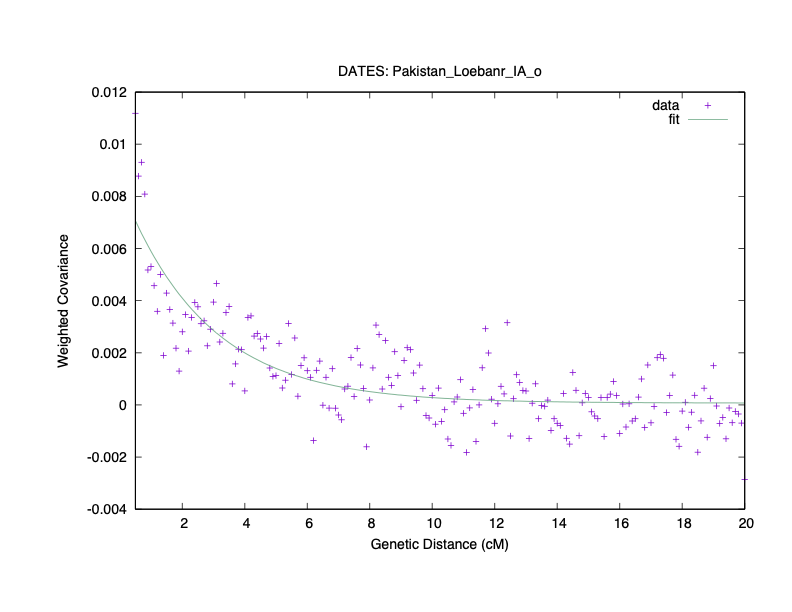

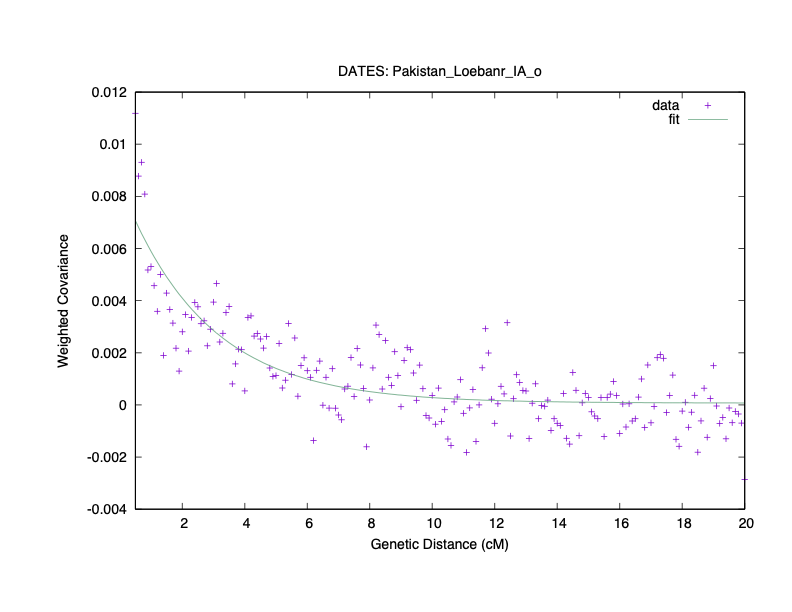

In Loebanr outlier

Now, we can look at one outlier Iron Age woman from the Swat culture who had particularly high steppe ancestry, and appeared to be an individual at the far end of the ANI cline. This woman proved to be a better proximal source of steppe ancestry for modeling modern day Indians than her Turkmenistan contemporary (another single sample that has been proposed as a source of late steppe ancestry). Where did this woman come from? Punjab would be a good bet. After all, her significant amount of AASI in combination with a relatively low Anatolian neolithic ancestry argues against a location in Central Asia. And modern day Punjabi / Haryana Jats and Rors are not far removed from her – e.g. I modeled a Haryanvi Ror sample as 16% Irula and 83% ancestry from a population akin to this woman. Therefore, it’s likely she was a migrant up from Gandhara or further south and can be used as a representative of higher caste Punjabis of her time.

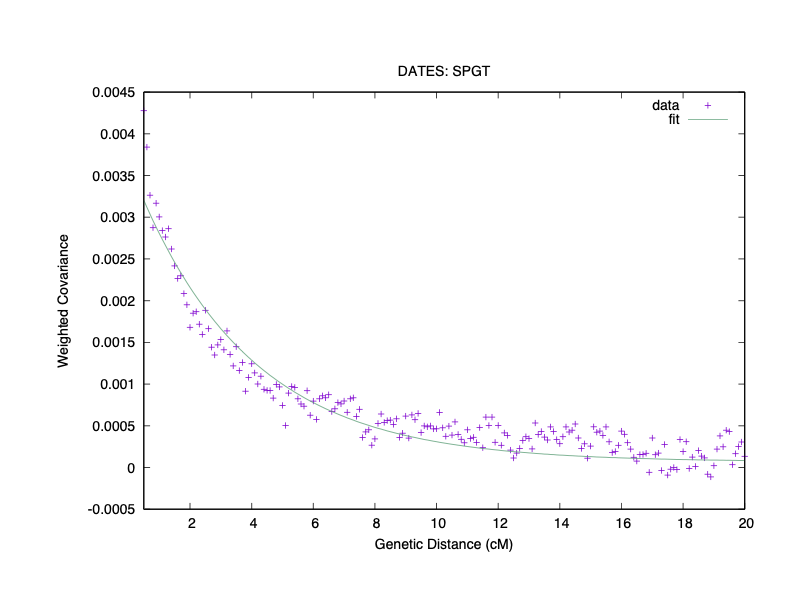

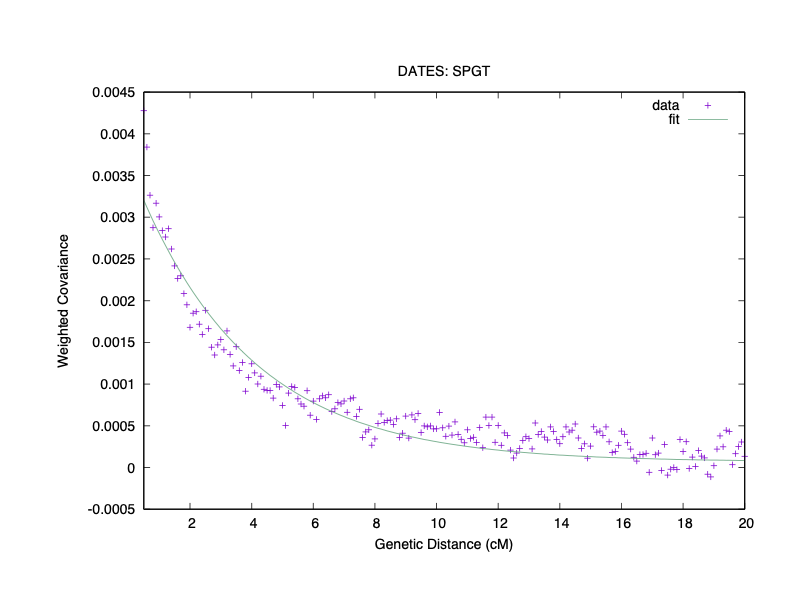

Let’s look at the DATES modeling for this woman:

mean: 37.593 std error: 13.239 Z: 2.840

nrmsd: 0.191

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 2714-1231 BCE

As is normal for a single sample, the data is somewhat noisy. Nevertheless, DATES is designed to be able to handle single target samples, and we have a good nrmsd score and a statistically significant result, albeit with a wide range. This would confirm that the woman came from a large population that had been well formed by the late 2nd millennium BCE. More crucially, the weighted covariance at large genetic distance is close to 0, indicating she was not for example a product of recent marriage between a high steppe migrant from Turkmenistan and a lower steppe inhabitant of Loebanr. However, let’s obtain a narrower estimate of admixture time.

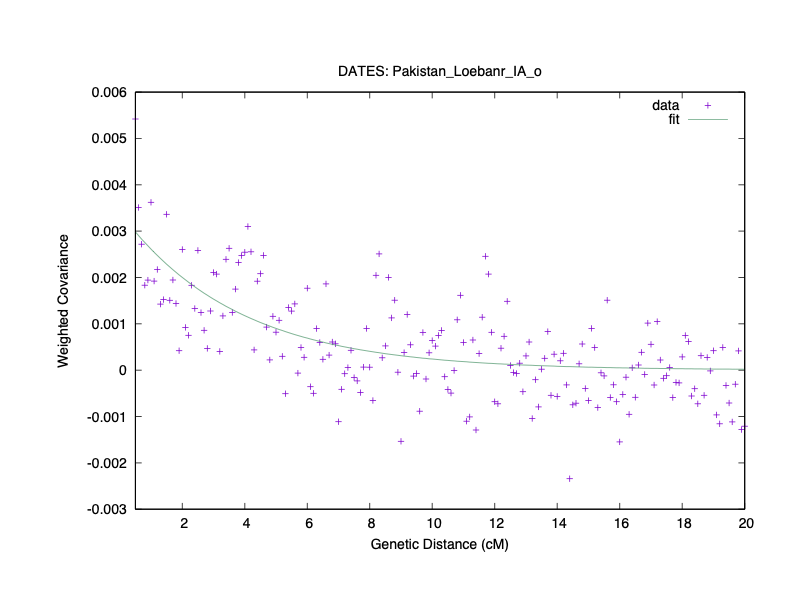

IVC-related as source

To improve the fit, in light of the low AASI proportion in the Loebanr outlier, we can use IVC and similar individuals high in neolithic ancestry but lacking in steppe ancestry as the source. For this group, I’ve used the IVC periphery samples in the Reich dataset, along with Aligrama (Iron Age Swat samples without steppe ancestry), and SiS-BA-1 (non-Indus-periphery samples from the Helmand culture, which have India-related ancestry).

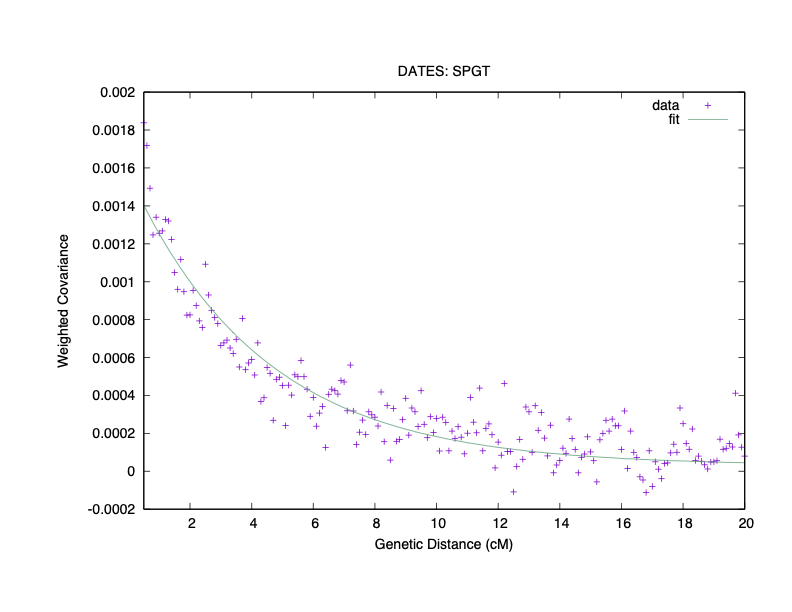

Once again, let’s check calibration against the results from the Narasimhan paper:

mean: 24.077 std error: 2.658 Z: 9.059

nrmsd: 0.101

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1743-1445 BCE

The nrmsd is somewhat worse but the results are essentially in line with the modeling using AASI-rich sources.

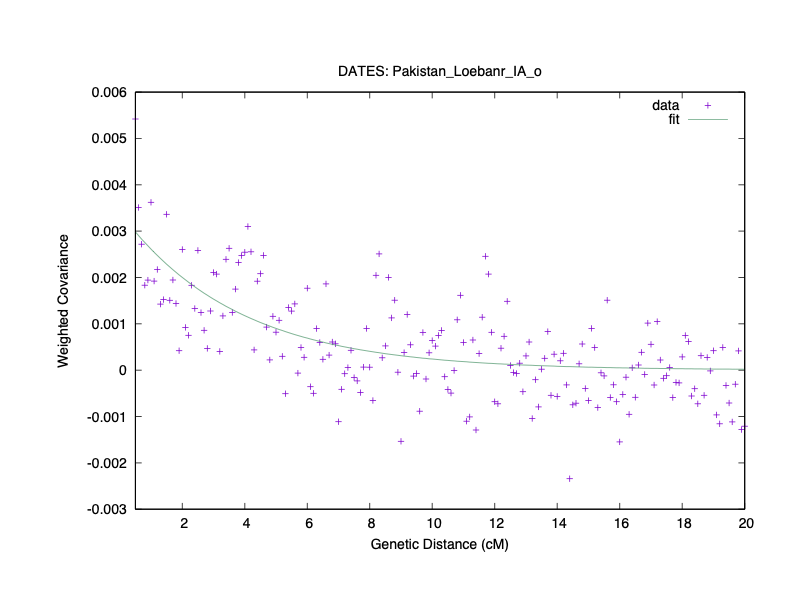

Now, let’s give it a go on the Loebanr outlier woman:

mean: 27.621 std error: 5.222 Z: 5.290

nrmsd: 0.356

Sample date estimate: 920 BCE

95% interval admixture estimate: 1986-1401 BCE

Due to noise, nrsmd worsened but is still well below 0.7. Notwithstanding this though, the shape of the curve fits like a glove and appears spot on with the average weighted covariance. And that good curve fit is reflected in the improved Z score and lower standard error. The result lets us conclude that the Loebanr outlier woman received her steppe ancestry admixture at roughly the same time as her Swat Valley contemporaries did.

Conclusion / Implications

To conclude, we’ve found evidence that high steppe ancestry may have reached the Ganga Valley by the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, and likely had reached Gandhara / Punjab by the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. Some of the steppe ancestry that entered Gandhara also traveled up into the Swat Valley in the same timeframe.

All of this evidence is consistent with steppe ancestry settling in the Punjab centuries prior to the composition of the Rigveda there, in conjunction with the observed spread of R1a-L657 in India which originated from the R1a-Z93 Y-haplogroup of the steppe. It’s also consistent with the beginning of formation of caste groups in the Kuru-Panchala Kingdoms around the time the varna system began to be implemented in the Iron Age Late Vedic Period.

We may also hypothesize that perhaps the people of the Swat Valley spoke old Burushaski. After all, the modern day Burusho people are located in the mountains further uphill from the Swat Valley, and genetically have some traits in common with the non-outlier samples of the Swat – viz. lower Sintashta ancestry and elevated IAMC (Aigyrzhal-like Inner Asian Mountain Corridor) ancestry. They have additional East Asian ancestry but this is consistent with a population that would have had trade links to the Tarim Basin, and the observed presence of Turkic and Tibetan loanwords in the Burusho language.

Note that while the evidence here indicates that there had already been substantial steppe admixture into India in the Bronze Age, it does not preclude additional later admixture of steppe ancestry in the Iron Age or Early Historic Period. Substantial admixture in this period is unlikely for a few reasons: lack of admixture from East Asian or Anatolian heavy groups (why would the groups resembling earlier steppe populations be the only ones to admix into India?), lack of migration of newer steppe-originated Y chromosome lineages, and the sheer size of the growing Indian population which would lessen the relative genetic contribution of migrants. But regardless though, the presence or absence of additional late steppe admixture does not have much of a bearing on the debate regarding the origins of the Indo-Aryan languages.