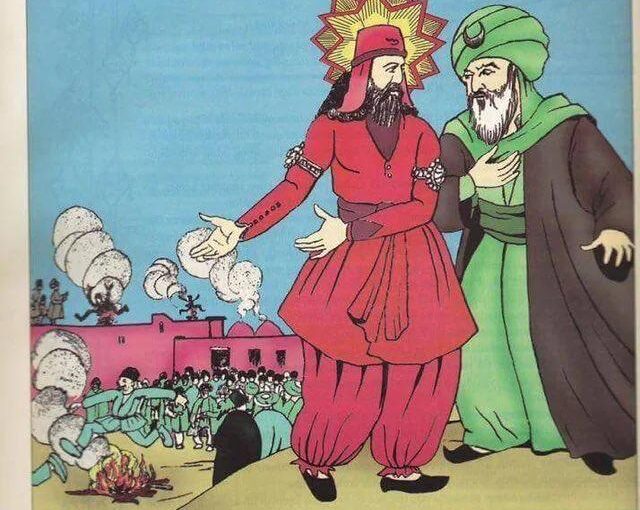

Sbarr sent a simple reel: a female Tamil Muslim politiciann in Ranipet, near Vellore, waving an LTTE flag during an election campaign. What followed was not simple at all. The reaction treated the image as an ideological provocation rather than a local political act. Why is a Muslim woman waving a Tamil separatist symbol? What does this say about loyalty, religion, or the nation?

Islam in South India did not arrive through conquest. It arrived through trade. Arab merchants settled along the Malabar and Coromandel coasts centuries before the Delhi Sultanate existed. They married locally, learned the language, adopted food, dress, and social habits, and became Tamil, Malayali, or Konkani Muslims. Religion changed. Civilisation did not.

This is why South Indian Islam does not behave like a foreign layer imposed on a hostile society. It is woven into the local fabric. Tamil Muslims are Tamil first in language, culture, and political instinct. Their solidarities are shaped by region before theology. This is not syncretism as rebellion. It is indigeneity as habit.

Tamil identity in Tamil Nadu routinely transcends religion. I was reminded of this years ago in Chennai, asking my dentist, who was Christian,about her name. Like many South Indian Christians, it was a mix of Hindu and Christian forms. I asked whether they were also Tamil. She looked at me as if the question made no sense. Of course she was Tamil, “very Tamil.”

That response explains more than a thousand editorials.

In Tamil Nadu, religion is real but it is not totalising. Tamilness is older, deeper, and more organising. This applies to Hindus, Christians, and Muslims alike. Political expression follows that logic. A Tamil Muslim expressing Tamil nationalist sentiment is not a contradiction. It is normal.

This is what happens when South India is constantly interpreted through North Indian assumptions. Islam is assumed to be oppositional. Symbols are assumed to be exclusive. Politics is assumed to be communal by default. None of this holds in the Tamil world.

Tamil lands occupy a distinct face of Indian civilisation. Fully part of India, yet unmistakably their own. Deeply Indian, yet not reducible to Gangetic history or North Indian templates. This is not fragmentation. It is civilisational strength.

India has always had multiple faces. The Tamil one is maritime, linguistic, ancient, and self-assured. It absorbed religions without surrendering itself to them. That is why its Muslims do not behave like guests. They behave like natives.

The reel was never the problem. The inability to see India’s southernmost face was.