For too long, the term Islamism has functioned as a lazy shorthand in Western discourse; one that often sanitizes the dehumanization and securitization of Muslim bodies. And when it’s used by those claiming spiritual insight, especially from within a global Faith like the Bahá’í Faith, it becomes more than just a rhetorical misstep. It becomes a betrayal.

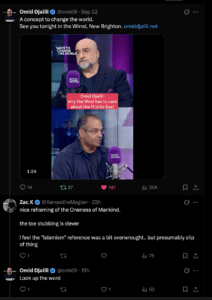

This week, a prominent British Bahá’í comedian made such a misstep.

A Moment of Caution — Dismissed

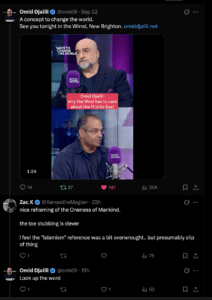

When Omid Djalili posted a news clip, which gently reframed the Bahá’í concept of the Oneness of Mankind, I appreciated the gesture. In fact, I said so. The “toe-stubbing” analogy was clever, and there was something moving in seeing profound principles gently repackaged for a wider audience.

But I raised one concern: the reference to Islamism. It was, I suggested, overwrought, unnecessary, and ultimately unwise. I proposed an alternative: perhaps rephrasing the same concern as “security anxieties around mass migration” or similar language that doesn’t dog-whistle. This wasn’t a condemnation. It was, as any Bahá’í should recognize, consultation. An invitation to reflection.

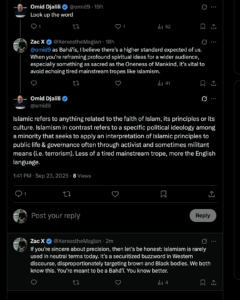

Instead, I was told: “Look up the word.”

The Burden of Bahá’ís in Public

It’s not about semantics. It’s about responsibility. And especially so when one is invoking sacred teachings, teachings that thousands upon thousands have died for; on public platforms. The Bahá’í Faith is not a marketing device to win over a Western liberal audience by soft-launching its principles in the language of border panic and counter-terrorism.

To reduce Islamism to a “technical English-language distinction” is disingenuous. The term has never been neutral. In nearly all Western contexts, it has become a floating signifier for violence, extremism, and “dangerous Muslims.” It serves to other, to isolate, and to justify state and vigilante violence often against entirely innocent people (Afghanistan, Iraq & Palestine).

And when Bahá’ís, of all people, repeat that language without self-awareness, without contrition, and without consultation, we should all be worried.

The Problem Isn’t the Joke. It’s the Response.

I understand the pressures of performance. I’ve done media. I know how easy it is to slip. What matters is what happens next. When another Bahá’í, someone you know, someone with many mutual connects, raises a concern gently and in good faith, the correct response isn’t smugness. It isn’t defensiveness. It certainly isn’t “learn English.”

That response is hurtful, racist, and deeply contrary to the values we both claim to serve. And that’s what cut. Not the line in the show but the refusal to listen afterwards. The arrogance of elite Bahá’ís who believe proximity to celebrity, applause, or power gives them carte blanche to reframe revelation in their own image.

This Is Why We Need to Talk

As Brown Pundits reshapes itself, I’m re-examining my own priors, too. What voices we platform. What values we uphold. Who gets to speak for our communities and under what banner.

So I say this plainly: The oneness of mankind cannot be proclaimed by marginalizing Muslims. And Bahá’ís, especially public ones, must hold themselves to the standard of humility, consultation, and truthfulness we profess to believe in. We cannot serve justice while echoing injustice. We cannot preach unity while casually reinscribing division. The world is watching. Let’s be worthy of what we claim.