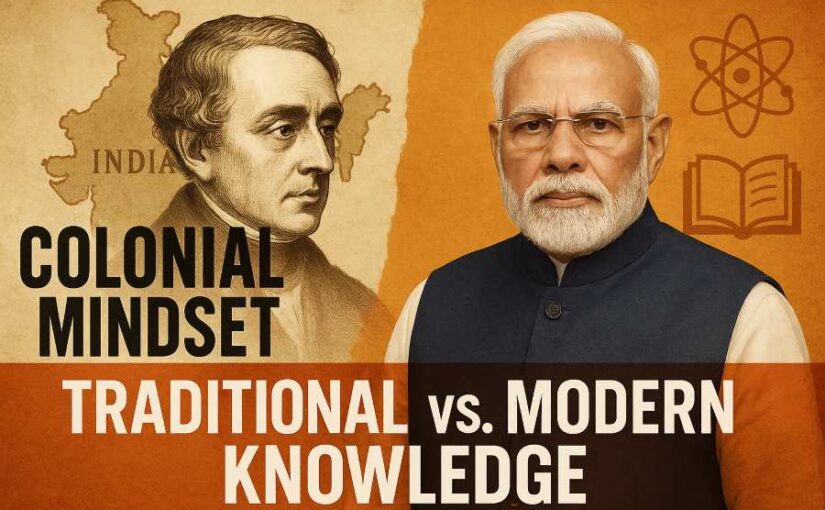

Rebuttal to When RSS-Modi Attack Macaulay and English, They Attack Upward Mobility of Dalits, Shudras, Adivasis

Follow-Up to Macaulay, Macaulayputras, and their discontents

A new orthodoxy has taken hold. It claims that criticising Macaulay or colonial education is an attack on Dalit, Shudra, and Adivasi mobility. English, we are told, was not a colonial instrument but a liberatory gift. Macaulay is recast as an unintended ally of social justice. This view is wrong. More than that, it is historically careless and civilisationally corrosive.

The Core Error

The mistake is simple: confusing survival within a system with vindication of that system. No serious person denies that English became a tool of mobility in modern India. No serious person denies Ambedkar’s mastery of English or its role in courts and constitutional politics. But to leap from this fact to the claim that Macaulay was therefore justified is a category error. People adapt to power structures to survive them. That does not sanctify those structures. To argue otherwise is like saying famine roads liberated peasants because some learned masonry while starving. Adaptation is not endorsement.

Macaulay Was Explicit

There is no need to guess Macaulay’s intentions. He stated them plainly. He dismissed Indian knowledge as inferior. He wanted to create a small class: Continue reading Macaulay, English, and the Myth of Colonial Liberation