This post is triggered by some posts from XTM in the past and some discussions on the BP whatsapp group.

This is not a referenced essay but more of a summary of my evolving position on the history jAti and varNa. I am neither a history or genomics scholar and this is an essay of a reasonably well informed layperson who has gone deep in the speculative prehistory of Indian subcontinent.

The first thing to note is the difference between jAti and VarNa.

jAti is a endogamous population – maps on to English word Caste. Identity into a jAti is a lived reality for billion Indians.

varNa is a hierarchical abstraction which is presented in Vaidik texts which does and doesn’t always map neatly on to thousands of jAti groups. I would wager that varNa mattered for the Brahmanas and at times to the Kshatriyas as their jAtis map neatly on respective varNas.

This post will focus on varNa, I will cover jAti in some other post briefly.

For a bit more on jAti: Early Hinduism – the epic stratification – Brown Pundits

on varNa:

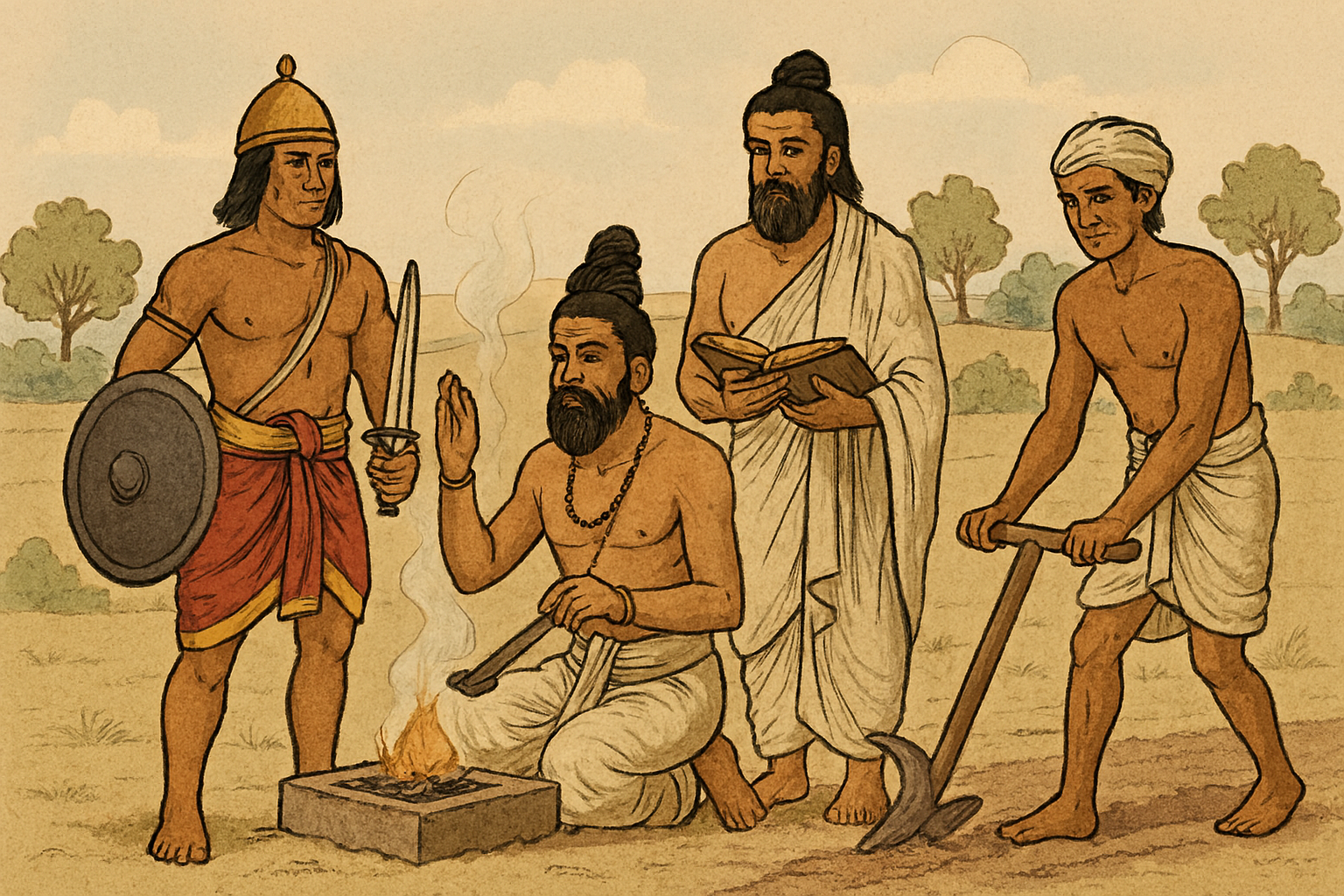

During the composition of the ṛgveda the priests and the warriors were the prime movers of the Arya society hence designated Brahmanas and Rajanyas. This bifurcation is common among a lot of society where the physical and spiritual power is owned by different elites who in a sense rule the society. These two communities were to become two Arya varNAs. The third varNa called the Vaishyas were originally the remaining people. The word Vaisya comes from Vish which means people. So all farmers, craftsman, artisans etc would come under the word Vaisya initially. This much can be asserted with certain degree of confidence.

The origin is the fourth varNa – Shudras is not as crystal clear but its safe to bet that initially the outsiders (non Arya) were called Shudras. The word is used to denote someone who doesn’t follow the proper Arya rituals at places or someone who is a defeated enemy or someone who is a labourer. So as Arya communities were forming during the early Vaidik period after the collapse of Harappan civilization, the outsiders who were defeated and assimilated were termed Shudras. This label also applied to populations outside the core Vaidik area who were kings and rulers in their own right in complex pastoral and farming societies. The cultures of Deccan and Peninsular India at this time would also fall in this bracket (precursors to speakers of Dravidian languages of today).

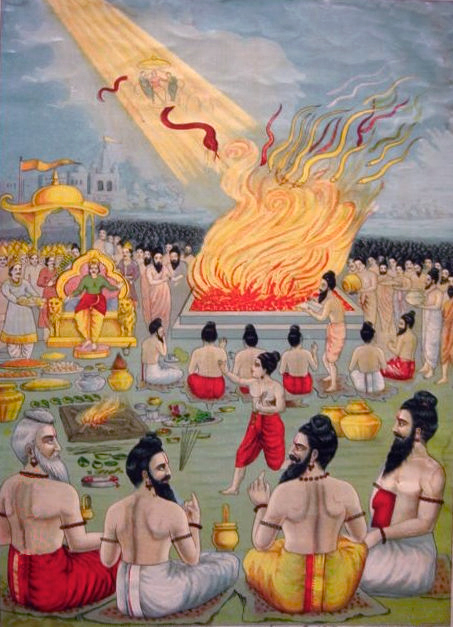

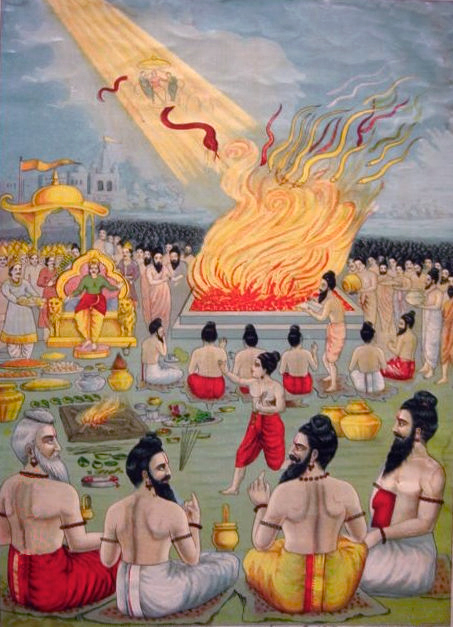

Aryavarta (Land of the Aryas) expanded mimetically through lavish sacrifices and tall poetic tales (later Epics). Instead of building complex structures, the Rajanya class (later Kshatriyas) from the core Indo-Gangetic region (Aryavarta), focussed their wealth on conducting extravagant sacrifices (Yajnas) like Asvamedha and Rajasuya to assert their strength. The template was set by Vaidik Rajanyas and slowly people outside the core Vaidik area began to emulate their peers. Non Arya rulers invited priests to conduct spectacular sacrifices to rival the Rajanyas. These Non Aryas were gradually assigned the Kshatriya varNa along with the original Rajanyas. I would wager that priests from non Arya cultures were assimilated into the Brahmanas. Those from outside who didn’t keep their power became the Shudras. But this designation also was by no means settled.

Every now and then we have Shudra monarchs especially in the Eastern and Southern part of the subcontinent. Its worth noting that even thought a dynasty may be of Shudra origins, they likely re-wrote their histories once they attained power. Some of these rulers claim to have conducted even grander sacrifices than the Kshatriyas 1.0 and 2.0. Conversely, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas who lost their power or wealth might have lost their varNa.

a-varNa

(Co-Pilot wouldn’t help me with a representative image as its termed offensive)

Even now a vast number of people were outside this matrix of abstract varNa and secular Kshatra. As AryaVarta continued to expand it encountered the people on the margins. The template of absorbing the elites into the elite varNas would slow down eventually. Every now and then the outsiders would not be integrated into the varNas but remain outside as a-varNas. When this became happening is debatable but its safe to assume that around the time of Manu smriti, Arya-Varta had a significant proportion of a-Varna population. Over time ritual status was assigned to the outsiders and they became the untouchables.

I think this practice evolved like slavery as suppling an eternal supply of low cost labor (especially for dirty tasks). The a-varNa need to be distinguished from the Shudras who could accumulate wealth and status. So it could be a combination of (a) tribes whose professions were deemed unclean (b) defeated people forced to do unclean professions or probably a combination of both.

Another group of people were to remain outside the Arya social system, the tribals. But it would be unfair to club the tribal communities with a-varNa. Tribal people had wide range of experience of interactions with the mainstream from domination and competition to servitude. Some tribes may have been absorbed into the a-varNa groups but that is not a generic template.

The varNa fluidity:

As Merchant guilds began becoming powerful around the times of Mahajanapadas, the Vaishya Varna began to become more associated with the Merchant class. Artisans, farmers and ordinary soldiers began to be associated with Shudra varNa. Today its quite common to associate the Vaishya varNa with traders and merchants but it wasn’t always so.

Similarly its quite possible that some a-varNa clans could lose their shackles but its fair to assume that this fluidity kept reducing in the common era. Last thousand years the varNas have not been fluid – especially for the a-varNas.

The Ossification:

I have written an entire blogpost on why the jAti-varNa matrix began to ossify and when.

Co-Pilot summary of this post:

The essay explores how early Hinduism’s caste stratification evolved through interactions between Vedic Brahmanical traditions and Sramana schools like Buddhism and Jainism. It argues that concepts of karma, rebirth, and dharma—emphasized by Sramanas—helped justify and ossify the Varna hierarchy, linking birth to karmic retribution. Over time, this moral dimension reinforced endogamy and rigid social divisions, especially during the Gupta era. The author speculates that pre-Aryan tribal endogamy combined with Vedic ritual purity and karmic philosophy created the uniquely enduring Jati-Varna system in India

The Kaliyug cope:

From the turn of the century, the subcontinent was always under attack from North West, Yavanas, Shakas, Kushanas, Hunas and final Arab and Turks. It is my belief (and also of some scholars) that the ideas of Kali-yug were a response to these invasions. A Yug when idealised Vaidik society was destroyed.

Islamic conquests of India began in the 7th century itself but it wasn’t till the 13th century that the entire subcontinent was touched by the crescent scimitar. While the concept of Kali-yug might be older than Islamic incursions into the subcontinent, I think they were imagined sufficiently during the Islamicate age. Some of the Brahamanas who survived (entire Shakhas of Vaidik learnings have been wiped out) saw Kaliyuga as the yuga where only 2 varNas exist – Brahmanas and Shudras. While some Kshatriya clans retained the memory of their ancestry during the Islamic time and reformulated as Rajputs, a lot of Kshatriyas and Vaishya lost the touch with their ancestry. While most of these groups have myths of their descent from Yadus or Ikshvakus, these claims did not get Brahmana (and Kshatriya) stamp of approval in the medieval times.

On psychological level one can understand this statement – Kali-yug contains only Brahmanas and Shudras as a coping mechanism opted under the yoke of Barbarians. Naturally wealthy landed castes who may have descended from Kshatriyas or Vaishyas were seen as Shudras. The Kadambas, Rashtrakutas, Yadavas, Chalukyas, Cholas, Gangas, Pandyas and Cheras all claimed Kshatriya descent. If this is assumed to have some merit, its not logical to assume that all the descendants of these dynasties and their power structures went extinct. Its more likely that the elites from medieval times became the wealthy landed and mercantile elites without some deviation (on the coattails of the brits).

Brits and modernity:

The Europeans began documenting varNa with the arrival of Portuguese (Casta). But the modern understanding began to truly take shape under the British rule. I will only quote the Co-pilot summary of Nicolas Dirk’s fantastic book here.

Nicholas Dirks’ Castes of Mind argues that the modern idea of caste as India’s defining social system was largely shaped by British colonial rule. While caste existed earlier, it was more fluid and intertwined with local, regional, and occupational identities. Colonial administrators, obsessed with classification, codified caste through censuses, ethnographic surveys, and legal frameworks, turning it into a rigid hierarchy. Dirks shows how this “ethnographic state” reified caste as the central lens for understanding Indian society, overshadowing other identities. The book highlights how colonial policies and scholarship created enduring structures that continue to influence politics and social life today.

In essence, varNa and social stratification is surely older than even the Roman colonisation of Britain, what we understand today as Caste is significantly shaped by the British intervention into India. The emerging economies have offered upward mobility for some while relegating others to medieval times. In many cases, artisan communities continue to see their economic status significantly degrade with mechanisation. Present Caste identities and economical realities are much more downstream of the economic exploitation and changing economy due to industrialization than abstractions like of Dharma-Shastras.

In the theatre of Indian democracy, the first-past-the-post script ensures caste takes center stage — louder, sharper, more enduring than ever before. And as present-day passions spill backward into history, they stir the ancient pot with fresh fervor, adding new tadka to a saga already simmering with spice and strife.

Post Script:

I am generally liberal with comments, but i will exercise moderation for repeated stupidity on this post.