for a period of 60 years after the death of the artiste….there are no descendants of Thyagaraja who can

claim copyright” ….“what is happening is that music companies claiming

copyright over the compositions are fooling the public”….”What

they are doing is known as ‘copyfraud’”…..

………………

Most of the North-South barriers have diluted over the past six decades. Food is the first thing to have been universalized, driven by truck drivers who primarily hail from the North (dhaba culture). Side by side, here in Mumbai you have the Udupi (idli-vada breakfast) culture and the Gujarati-Rajasthani thali culture. There are now many N-S marriages in our circle and we have even Bollywood spoofs about marriages (mostly super-caste though).

…

The most durable division seems to us is in classical music- Carnatic vs. North Indian. There are too many super-stars and their followers who believe in rigidity and purity (nothing wrong with passion though).

It is past time to create a Classical Music Hall of Fame and for the fans on both sides of the Vindhyas to acknowledge the masters (we use Vindhya figuratively, however as Prashanth Kamath reminds us, Northern Karnataka is a hub for Hindustani music and the home of another super-man Bhimsen Joshi, thanks Prashanth). And when they do that we expect Thyaga-Raja to be the first among equals (our opinion).

….

As far as the music companies are concerned they cant be faulted for engaging in standard corporate thuggery, after all everybody else does it. Youtube merely wants to steer clear of any legal battles. It is the society of fans (and there are millions of them) who need to engage and tell the corporates to back-off. It will be also a good idea to petition to our pitiful politicians to stop the squabbling and start something meaningful to emphasize public ownership of works of (classical) art.

….

Early mornings in Chennai or Hyderabad, along with the azaan call and

ringing of temple bells, amidst the aroma of steaming idlis and filter

coffee, the strains of a Thyagaraja kirtanai too will waft in the air.

But who owns Thyagaraja’s music? Big music labels claim it’s theirs and

music channels on YouTube that upload videos of Carnatic music concerts

face their wrath and an unequal battle.

….

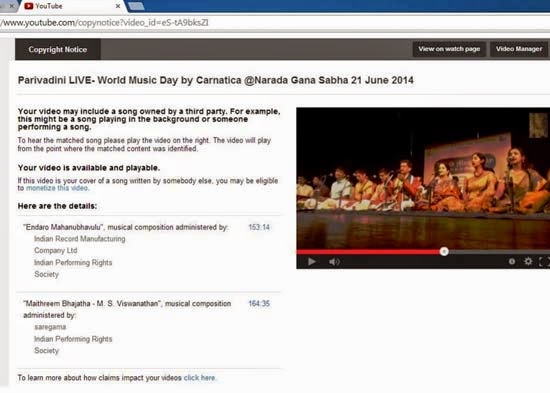

Parivadini, a music channel that uploads performances of Carnatic

classical music, including renditions of compositions of the legendary

Thyagaraja (1767-1847)—composer of over 24,000 songs of which about 700

are extant—is the most recent victim. It had, after taking permission of

the organisers and performers, uploaded live webcasts of concerts of

Carnatic music where Thyagaraja’s compositions were being sung.

Last

month, Parivadini got a notice of copyright infringement from YouTube

for a recording it uploaded, as a music label claimed the Thyagaraja

composition (and not that particular recording—they claim, ludicrously,

ownership to the original composition itself) as their property. When

contacted, YouTube responded that when Parivadini submitted a counter

notification, the matter was probed and the video reinstated.

“But it

is not just a one-off incident,” says Lalitharam Ramachandran,

co-founder, Parivadini. “It’s a constant fight between YouTube music

channels like ours and music companies. And this case-to-case-based

solution by YouTube is not a permanent one. For the channels it

becomes a nuisance.” ….

….

Adds Carnatic vocalist Sangeetha Sivakumar, “It

is sad that music labels make such claims. It shows their insensitivity

and lack of understanding of our art form.”

….

Musicians say the algorithm which YouTube uses to identify potential

infringements needs to modified to make it sensitive to the demands and

intricacies of classical music. There should not be blanket application

of technology to all forms of music without understanding the nuances.

The continuing potency of ‘copyright claims’ vis-a-vis YouTube poses

problems, threatening the very survival of music channels.

If they

receive three copyright (CR) strikes, or three legal notices claiming

copyright violations, the channel itself gets terminated. Even a single

CR strike leads to loss of access to several YouTube features. Of

course, when a channel faces a partial crackdown or a total blackout, it

is denied a fair opportunity to make money too. If copyright violation

claims go undisputed, the money goes to the labels. S.A. Karthik, a

Bangalore-based lawyer and a musician, finds it hard to believe that

anybody can claim copyright over the compositions of Thyagaraja, because

they are clearly in public domain.

Clearly, there is a need to distinguish between ground-level

copyright over compositions and copyright over sound recordings

performed by artistes. Anybody who deals in a sound recording, the

rights to which have been acquired by a recording label, without the

latter’s permission, infringes the label’s copyright.

But anybody who

wishes to perform the same composition as that of the recording can do

so without permission from the music label, as long as it is in public

domain. This is because there can be no copyright over such songs.

“Under present laws, copyright protection on a particular artwork lasts

for a period of 60 years after the death of the artiste. But in this

particular case, since there are no descendants of Thyagaraja who can

claim copyright, and he has been long dead, there can be absolutely no

claim of copyright on his songs,” says Shamnad Basheer, formerly with

Intellectual Property Law at the National University of Juridical

Sciences.

“But what is happening is that music companies claiming

copyright over the compositions are fooling the public,” he says. What

they are doing is known as ‘copyfraud’, where they lead the public into

believing that they are the true copyright holders of various artworks,

and thus extract royalty from unsuspecting small channels.

….

This is not unique to classical music. A lot of collecting societies

(those who manage the rights to music on behalf of labels) have been

doing this—they extract money from restaurants, clubs and so on,

claiming copyright over the music being played.

…..

Copyright lawyers say

the reason why it still continues is because big labels still haven’t

been confronted by an opponent strong enough for a bare-knuckle showdown

in court. “These are big companies with resources, unlike small music

channels like us, who often do not engage in fightback,” says

Lalitharam.

….

The need perhaps is for small channels to come together and fight as

a group. At stake is the survival of a relatively niche space like

Carnatic music on YouTube.

…..

[ref. Wiki] Kakarla Tyagabrahmam (May 4, 1767 – January 6, 1847), colloquially known as Tyāgarāju or Tyāgayya in Telugu, Tyāgarājar in Tamil, was one of the greatest composers of Carnatic music or Indian classical music.

He was a prolific composer and highly influential in the development of the classical music tradition. Tyagaraja composed thousands of devotional compositions, most in praise of Lord Rama, many of which remain popular today. Of special mention are five of his compositions called the Pancharatna Kirtis (English: “five gems”), which are often sung in programs in his honor.

Tyāgarāja began his musical training under Sonti Venkata Ramanayya,

a music scholar, at an early age. He regarded music as a way to

experience God’s love. His objective while practicing music was purely

devotional, as opposed to focusing on the technicalities of classical

music.

….

He also showed a flair for composing music and, in his teens,

composed his first song, “Namo Namo Raghavayya”, in the Desika Todi ragam and inscribed it on the walls of the house.

…

After some years, Ramanayya invited Tyagaraja to perform at his house in Thanjavur. On that occasion, Tyagaraja sang Endaro Mahaanubhavulu, the fifth of the Pancharatna Kritis.

Pleased with Tyagaraja’s composition, Ramanayya informed the king of

Thanjavur of Tyagaraja’s genius.

….

The king sent an invitation, along with

many rich gifts, inviting Tyagaraja to attend the royal court.

Tyagaraja, however, was not inclined towards a career at the court, and

rejected the invitation outright, composing another kriti, Nidhi Chala Sukhama (English: “Does wealth bring happiness?”) on this occasion.

….

Angered at Tyagaraja’s rejection of the royal offer, his brother threw the statues of Rama Tyagaraja used in his prayers into the nearby Kaveri river. Tyagaraja, unable to bear the separation with his Lord, went on pilgrimages to all the major temples in South India and composed many songs in praise of the deities of those temples.

….

It is said that a

major portion of his incomparable musical work was lost to the world

due to natural and man-made calamities. Usually Tyagaraja used to sing

his compositions sitting before deity manifestations of Lord Rama, and

his disciples noted down the details of his compositions on palm leaves.

After his death, these were in the hands of his disciples, then

families descending from the disciples. There was not a definitive

edition of Tyagaraja’s songs.

…

The songs he composed were widespread in their popularity. Musical experts such as Kancheepuram Nayana Pillai, Simizhi Sundaram Iyer

and Veenai Dhanammal saw the infinite possibilities for imaginative

music inherent in his compositions and they systematically notated the

songs available to them. Subsequently, indefatigable researchers like K.

V. Srinivasa Iyengar and Rangaramanuja Iyengar made an enormous effort

to contact various teachers and families who possessed the palm leaves.

K. V. Srinivasa Iyengar brought out Adi Sangita Ratnavali and Adi Tyagaraja Hridhayam (in three volumes). Rangaramanuja Iyengar published Kriti Mani Malai in two volumes.

…

Out of 24,000 songs said to have been composed by him, about 700 songs remain now. In addition to nearly 700 compositions (kritis), Tyagaraja composed two musical plays in Telugu, the Prahalada Bhakti Vijayam and the Nauka Charitam. Prahlada Bhakti Vijayam is in five acts with 45 kritis set in 28 ragas and 138 verses, in different metres in Telugu. Nauka Charitam is a shorter play in one act with 21 kritis set in 13 ragas

and 43 verses. The latter is the most popular of Tyagaraja’s operas,

and is a creation of the composer’s own imagination and has no basis in

the Bhagavata Purana.

Tyagaraja Aradhana, the commemorative music festival is held every year at Thiruvaiyaru

in the months of January to February in Tyagaraja’s honour. This is a

week-long festival of music where various Carnatic musicians from all

over the world converge at his resting place. On the Pushya Bahula

Panchami

thousands of people and hundreds of Carnatic musicians sing the five

Pancharatna Kritis in unison, with the accompaniment of a large bank of

accompanists on veenas, violins, flutes, nadasvarams, mridangams and ghatams.

A crater on the planet Mercury is named Tyagaraja.

…..

Link: http://www.outlookindia.com/printarticle.aspx?291416

…..

regards