A short introduction to the work of Muzaffar Ghaffar, who has published 30 volumes of classical punjabi poetry with detailed explanations and translation. Written by Punjabi writer Nadir Ali (who happens to be my father)

Muzaffar Ghaffar on Guru Nanak

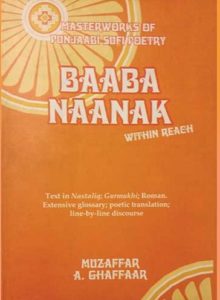

BAABA NAANAK Within Reach – in MUZAFFAR GHAFFAR’S series “Masterworks of Punjabi Sufi Poetry”

Publisher :Ferozsons (Pvt) LTD Pages : 435 Price : Rs 1095

In the cultural wasteland that is our homeland these days, to be a man of culture doesn’t take much effort; you do some literary chit chat or somehow get your name printed with some work people assume as cultural or creative and you become a cultural or literary figure! Having known Muzaffar Ghaffar for over thirty years, he is an honourable and notable exception to this superficial trend. He came to Pakistan with his savings and a couple of books in print, a book of English verse which has had a couple of editions published and a book On How a Government is Run . In my involvement with Punjabi we came together in the weekly “Sangat” in readings of Punjabi classic poetry held at the residence of Najm Hosain Syed and Samina Hassan Syed and I have had the pleasure of knowing him for over 30 years now.

A digression first: Najm Sahib is already famous in Punjabi literary circles in both East and West Punjab. To give you some idea I often quote a well-known Sikh scholar of Punjabi who was Head of Punjabi Department at Guru Nanak University, Amritsar. He said, “There are two categories of Punjabis – those who have studied Mr. Najm Hosain Syed and those who have not; those who have not read him do not know much about Punjabi language or literature!” To those not familiar with Mr. Najm Hosain Syed’s work, this may sound like an exaggeration. But having attended weekly meetings at his house for nearly forty years and having read his poetry and books on literary criticism, plays and poetry, I venture to share this remark. There are almost forty books of verse and landmark works of literary criticism and four books combining half a dozen plays in Punjabi to his credit. He keeps his books small so that the price remains within reach of Punjabi readers. “Recurrent Patterns in Punjabi Poetry” is his masterwork and the full text is online at apnaorg.com.

Najm is Muzaffar’s guide and inspiration for the thirty volumes of the “Within Reach” series on Punjabi Classical poetry that are available to date, all in English. But neither in the US, nor in England and rest of English speaking world abroad have I seen these books in the market, although Punjabi literature is taught in many places in institutes of repute in these countries, with considerable Punjabi speaking public. Nor do I know of anyone abroad who talks of these books. In particular the worth and value of this remarkable volume “Baaba Naanak Within Reach” on Baba Nanak’s poetry is incalculable, and it is our enormous loss that this work of M. Ghaffar remains largely unknown.

These books of Mr. Ghaffar are the result of years of eight hours of daily hard labor with no interruption. This is the kind of routine that has to be seen to be believed. A sister of Mr. Ghaffar used to live with him, and occasionally came to the literary programs he arranged under the banner of LEAF (Lahore Arts Forum). One morning we heard the sad news of her passing away. Being that she was my wife’s college mate at Home Economics College, she wished we go and condole. With such a personal loss to reckon with, we were surprised to find him working with utmost dedication. This is only symptomatic of the style of life he had chosen. In addition to his daily writing routine, he was also arranging weekly poetry readings and singing of kafis and classical poetry by late Mrs. Samina Hasan Syed, wife of Mr. Najm Hosain Syed. These would be held at Alhamra Hall 3 in Gaddafi Stadium. In addition he arranged Punjabi readings, in which I was a member of his team. Poets and scholars were personally requested by him to share their work and many spoke by such invitation and literary audiences held LEAF in great respect. Sessions were repeated every week at Model Town Library. Being a Model Towner himself, he knew that the general audience there mostly stays confined to that township in the after-hours! He tried his utmost to expand the interested audience and readers.

I assisted him in my humble capacity at the Alhamra Hall 3 events. After a couple of decades in operation, literary programs in this hall were discontinued by the authorities. Having not seen any activity there, I think the governing bodies cater to wild birds, who too have no real access to the mostly locked up three halls and an open air stage!

But Muzaffar’s daily labor of love come rain or shine continues ! A spectacular six volumes on Waris Shah’s Heer came out two years back, and two more classical texts are in progress. As a humble student and writer of Punjabi I can vouch this work will endure ! To encourage readers to not remain oblivious to its rich contents and do justice to this work, I am including a selection from the book. This will give readers an idea of Muzaffar’s style of explication. I copy below a selection from Nanak’s poetry with its translation and notes as given in his book :

Notes on the above selected poetry : {Written by Muzaffar Ghaffar ; these are quoted here directly as appear in his book}

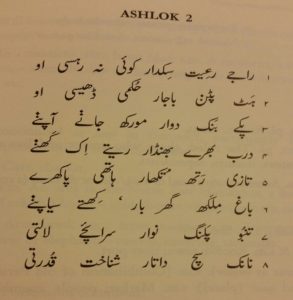

“Baaba Naanak used virtually all known forms of folk poetry. He used many metres and styles. He wrote long poems (vaars), kaafis (poems with refrains), ashloks (poems of several styles), dohrae (couplets), paoris (ladders), etc. He used available forms to suit his needs and purposes. This poem is a paori from a long vaar. Most of the poet’s work was named after musical raags.

In a paori, as in this one, the rhyming device is in the middle of the line, not at the end. In this poem Baaba Naanak uses two rhyming devices, one in the middle and one in the end. The usual way of using couplets is not used in the paori. Each line is complete in itself. The rhyme in the middle of the line is the same throughout the paori. The end rhyme used by the poet changes in every couplet. The middle rhyme maintains a relationship of the couplets. The metre is delicious and powerful. This promoted a specific style of reading. The second part of each line is shorter. This gives a special feeling.

lt includes many Pahari (of the hill regions) words, many Sanskritised words and also the special language of Sants and Saadhus (Hindu religious mendicants), which was called Sidh Bhaasha or Siddhokri. This language was used much in the Bhakti Movement (in which 3-5000 years of separation of ‘classical language’ and ‘folk language’ was increasingly seen). Here we see Arabic, Persian and ‘classical language’ melded together. That too had been happening for 4-5 centuries upto the poet’s time.

Line 1 :

Raajae raiyyat sikdaar, koi nah rahsi O

King, subjects, royal officers, none will remain at all

Kings, those who accept their kingship (the subjects), and royal officers, no one will remain, says the poet. All temporal authority and those who accept that authority are reminded of the transitory nature of authority itself and those who wield it. The end rhyme of this and the next line carries a tone that is strong and almost taunting – almost a sneer that is offered when someone resists a known fact or experience and has to be reminded forcefully.

Line 2 :

Hat pattan baajaar, hukmi dhaesi O

Shops, towns, bazaars, by Order will fall

Busy shops, flourishing cities, and much-frequented markets, all will fall. Here the poet brings in an essential ingredient of his beliefs and philosophy. All these are not only susceptible to natural cycles but also to the Order of nature. This will happen because it is so Ordained. We can see here a glimpse of Transcendental God, and his Order.

Line 3 :

Pakkae bank doaar, murakh jaane aapnae

Stylish, strong doors, fools consider their own

The doar (door) has a special meaning in the verse of Baaba Naanak. Getting to the door is the objective of cultivating the self. Only fools consider that the stalwart doors are theirs for the asking. There is also a concern here for considering whatever is made of brick and mortar as the door. The implication is that the door is reached through inward discipline and devoted practice.

Line 4 :

Darb bharae bhandaar, reetae ik khanae

Storehouses filled with treasures, in a moment will be empty

Warehouses full of treasures will be emptied in a moment (by others who are stronger and win wars; thieves; misfortune, etc.). Again the theme of impermanence of all that we cherish and hoard is present. The experience of Baaba Naanak – who had been a storekeeper in the service of Daulat Khan Lodhi, the governor of the Punjaab – showed him this phenomenon, time and again.

Line 5 :

Taazi rath tukhaar , haathi pakhrae

Arabians, chariots, chargers, elephants in armoury

Horses of all kinds – those which came from the east or the north (etc.) – as well as elephants in armour (will not remain) . The images of strong stallions and magnificently armoured elephants come before us. They too will not stay in these roles, says the poet, and could (indeed would) be put to other uses. The power they provide to their owners will be lost. The historical context here is of some Arabs and more Central Asians who came as conquerors. Then they were conquered by the land and stayed on. This cycle of history has happened before the Arabs and Central Asians came, such as the Aaryans, non-Aaryans and the pre-Aaryans who came to the Indus basin from Central Asia and or Iran. But the more immediate invaders are focused on by the poet (which included his employer). He does this by mentioning the sources of the horses. And he puts in elephants to bring in ‘local’ invaders also.

Line 6:

Baag milakh ghar baar kithae syaapnae

Dominions, households, orchards, where will they be known

Gardens, dimensions, households (all that we recognize as our own), will not be recognized as such. The word Kithae (where) makes us consider the situation after the event as well as , ‘in other circles’ . Perhaps we are being told that they will return to nature. Or not recognizing our ’ownership’ others will take over.

Line 7 :

Tanbu palang navaar, saraaecae laalty

Pavilions, tape laced beds, little inns desirable

Pavilions and comfortable beds and inns which provide comfort (all will go away or we will not be able to use them). Upto now we may see what we today may consider as a collection of clichés. There is no particularly new thought or imagery (though the armoured elephants and rearing stallions stay in our minds). What then is special about this poem. We may find some answers in the last line.

Line 8:

Naanak sach daataar, shanakhat qudrati

Naanak truth is the giver, recognition natural

This line affirms that Truth is the giver. This is recognized by nature. Or that nature gives us the recognition of Truth. All the above is the recognition of excess. And Truth is the ultimate source of life. Truth is God. Another reading, that Naanak is the truth giver is read by some devotees but Baaba Naanak’s humility may not permit such a claim.”

The prices of books in the series produced by him are rather steep, but having read all the books, I can vouch for both their quality and the value of the translation into English verse, as well as the commentary and detailed glossary of Punjabi words and their literal as well as symbolic meanings. This is a classic work of which time and scholars of today and the future would be better judges!

Omar Bhai

What;s up with the sudden Pakistani love for Nanak (and Punjabi stuff in general)? I am not one of those “Its a Khalistani thing” Indian, but somehow this time around its seems genuine and (dare i say) different.

Is it more like “Absence Make The Heart Grow Fonder”

I think there are few genuine nationalisms available to Pakistani Punjabis other than Punjabi nationalism. And Sikhs and Sikhism definitely give Punjab a very unique and definite identity, something like Jews and Israel.

” few genuine nationalisms available to Pakistani Punjabis other than Punjabi nationalism.”

I think it would be an odd nationalism where the language of the province is basically banned in schools and the state legislature.

Yes, its not a substantive, meaningful nationalism in any way, but it does provide some talking points.

Pakistani is a nationality while Punjabi is an ethnicity. Pakistani Punjabis are the majority of the population and basically run the country. That’s why they are quite willing to sacrifice Punjabi “nationalism” at the altar of Pakistaniat.