A potential watershed event in India’s modern economic history passed by recently. A state of the art, globally recognized, electronic product is to be made in India for export to the world.

Apple announced plans to make its latest phone model – iPhone 14 – in India, a significant milestone in the company’s strategy to diversify manufacturing outside of China.

Five percent of iPhone 14 production is expected to shift to the country this year, much sooner than analysts had anticipated.

While Apple is big, a more telling example of India’s potential is at the end of this post. But before that, how did India, a country that struggled to feed itself in the 1950s, get into the running for ‘factory of the world’ ?

In 1950, less than 1% of Indian college students studied science and engineering. By 2022, this number had risen to more than 30%. In fact, science and engineering have become so popular in India today, that a counter culture has arisen in the form of movies like 3 Idiots. Back in 1950, India’s best students were focused on subjects like law and social sciences, primed to manage the Empire. In fact, some have remarked that the independence movement was a result of the British producing too many lawyers in India.

Since independence, a concerted effort has been made by the Indian state to popularize science and engineering. This was done under the aegis of spreading a ‘scientific temper’, starting with the establishment of Vigyan Mandir in 1953. Subsequently, following in the legacy of medieval India’s Jantar Mantars, Nehru planetariums were established in major Indian cities. Further, the establishment of the IIT system gave a formal structure and high standard to engineering education. In 1976, the cultivation of scientific temper was included as a fundamental duty in the Constitution.

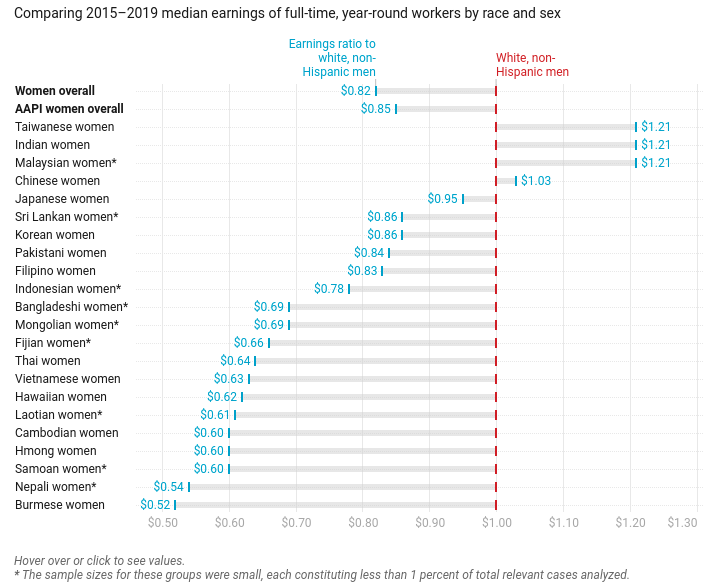

By the late 1970s, India’s growing pool of scientists and engineers had attracted attention from abroad, specifically Japanese automakers. This resulted in a dramatic increase in India’s automobile production, more than doubling from 700,000 to 2 million in the 1980s. An entire ecosystem of vendors producing automobile components came up around Suzuki’s Gurgaon factory. It is perhaps surprising that the Indian government did not think about replicating this success in the electronics sector. This oversight turned out to be an enormous missed opportunity.

An entire ecosystem of vendors producing automobile components came up around Suzuki’s Gurgaon factory. It is perhaps surprising that the Indian government did not think about replicating this success in the electronics sector. This oversight turned out to be an enormous missed opportunity.

The post 1990 period saw an acceleration in India’s economic growth, with the software and IT sector taking a prime position both in the export numbers and the economic narrative. However, India was a manufacturing star as well, particularly its pharma, petrochemical and automobile industries.

However, its potential in the wider manufacturing arena remained unrealized and indeed unrecognized. The late 2010s produced new exigencies in the global order, with Western countries trying to pivot away from their dependence on China. In this process, India has emerged as the only real alternative to achieve the technical complexity and economies of scale demanded by modern industry.

An equally important turn of events has been the precipitous decline in India-China relations. If Chinese support for Pakistan had made Indians wary of the CCP, its direct clashes with India on the border have made China enemy number one in the Indian public’s eye. There is a determination at the political and public level to not depend on Chinese manufacturing imports. This mark has already been achieved for toys, cell phones and PPE. Make no mistake, India wants to bring Chinese imports down to zero. This is what ‘Atma Nirbhar Bharat’ (self reliant India) really means.

On the other hand, Western business seems keen to move out of China. The LA Times describes the experience of one European manufacturer to move away from China,

In 2019, he began assessing the possibility of moving some manufacturing capabilities to Vietnam. But he abandoned the plan eight months later after price increases for about half of the company’s projects upset his customers. Product development also took longer — one prototype that would have been completed in three weeks in China required six months in Vietnam.

A review of other countries in Southeast Asia proved even less fruitful, he said.

By late 2020, Gaussorgues turned farther afield — to India. The local electronics and automotive ecosystem offered lower manufacturing costs and easy access to parts. With five employees so far, he aims to start assembly work next year, and hopes to host the majority of manufacturing there after five years.

What is important to note here is that India being able provide an alternative to China is not about the population. SE Asia, where the person in the article first when to has enormously populated countries, all with fantastic port access. India is able to provide an alternative because of the consistent emphasis on science and technology education over the past 70 years.

If you build it, they will come. Eventually.