Happy Birthday Pradhan Mantri:

I watched several videos — four or five, maybe more — of public figures sending their wishes. Among them: Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, Benjamin Netanyahu, Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, Mohammed Siraj, and Mukesh Ambani.

Mukesh Ambani, of course, remains closely aligned with the establishment, and Aamir Khan seemed to lean heavily into his Hindu heritage — adorned with Rakhis on his wrist, even a Bindi. He’s presenting himself now in a distinctly Hindu cultural idiom, though he comes from a very prominent Indian Muslim family.

By contrast, Shah Rukh Khan stood out. His message was subtly sardonic — he remarked that the recipient was “outrunning young people like me.” It was light, but just subversive enough to feel intentional. Interestingly, both Shah Rukh and Aamir spoke in shuddh Hindi, which added a certain performative weight to their gestures.

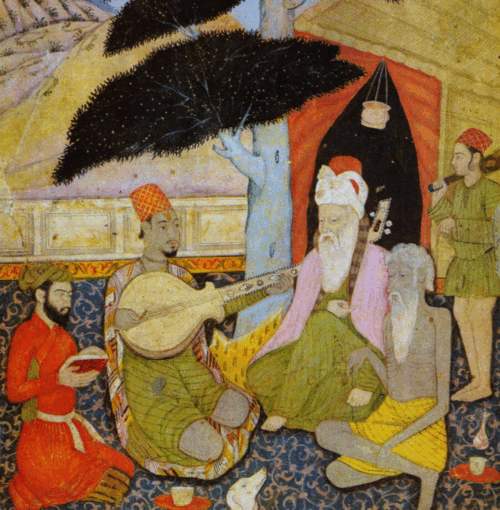

Hindu Art

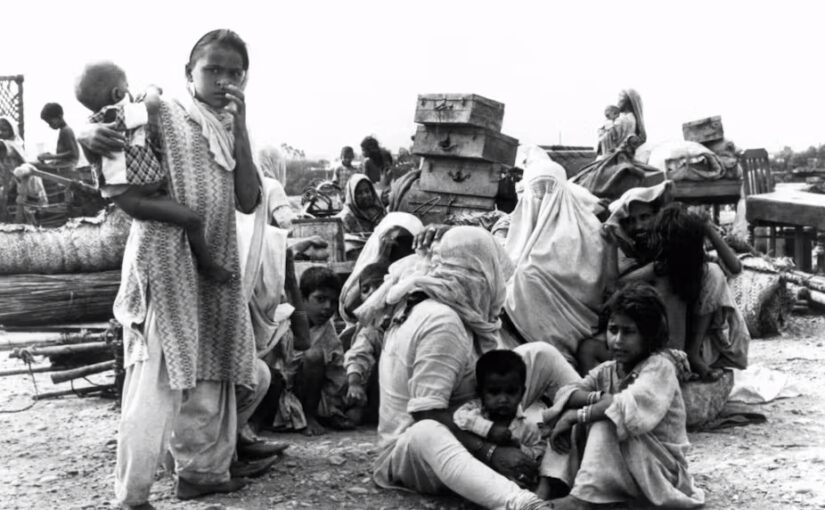

I’ve been fairly busy the past few days, mostly focused on BRAHM Collections; writing about carpets, curating Trimurti sculptures, and exploring Ardhanarishvara iconography. It’s been a deep dive into the civilizational grammar of India and by extension, the porous boundary between sacred art and civil religion.

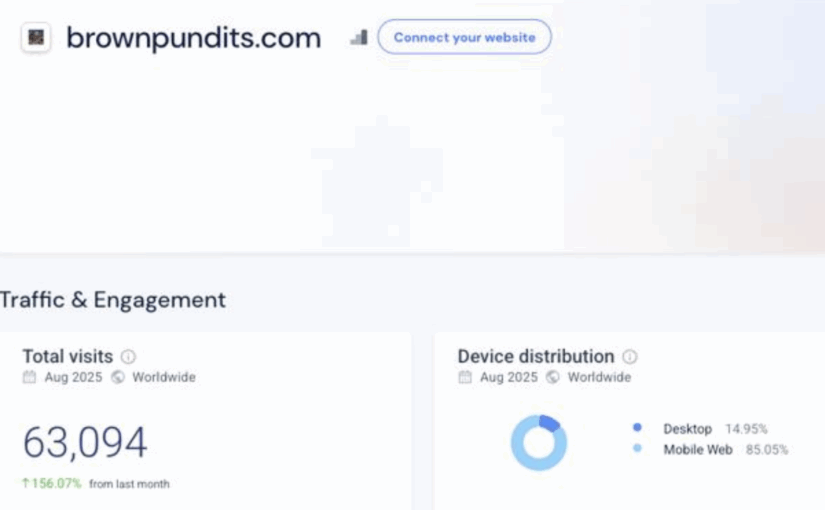

In the background, I’ve also been chipping away at longer-form reflections; trying to crack the formula for my newsletter (believe it or not the readership is neck to neck with BP but different demographics). It’s all a bit scattered, but the writing has become its own brown paper trail.

On the Commentariat (and Why I’m Stepping Back)

I still follow the commentariat but I’m slowly easing off. There’s a rhythm to it, sure, but too often it turns into exhaustion. I’ve removed all of Honey Singh’s abusive posts. Abuse is now a hard red line for me, but beyond that, I’m stepping back from constant moderation or sparring. Continue reading Threads, Carpets, and PM Modi’s 75th