The pluralism in Hindu thought is often pegged back to the philosophically sophisticated एकं सत् विप्रा बहुधा वदन्ति from Rgveda – first mandala. While that message underlies a lot of Hindu thought as we know it, it’s often overstated as it sounds sophisticated to the scholars/amateurs studying it. On the other hand, some hymns from the family books, particularly the Rgvedic Hymns 7-82 to 7-89 give a fascinating peek into the mind of the Bharata purohit Vasishta after the Dasarajna Yuddha. The hymns which are very repetitive mostly praise Indra and Varuna for the help given to Sudas(Bharatas) and the Trstus in the Dasarajna where the enemies also worshiped Indra. The important point to glean here is the different functional roles for which these deities are evoked. Indra for war, Varuna for prosperity, Aditi for light, etc. Varuna who is often paired with Mitra or Aryaman, gets paired with Indra here – which scholars (RN Dandekar, Michael Witzel, etc) see as conciliatory.

According to Dandekar, it was out of this experience of bhakti that Vasistha became essential in the conciliation of the Indra- and Varuna-cults and especially in “averting a schism in the Vedic community” by demonstrating “that Varuna and Indra were not antagonistic to each other but… essentially

complementary. ‘Indra conquers and Varuna rules.”

It is fair to speculate that such a conciliatory approach would go on to shape interactions the mainstream Vedic thought would have with non-Vedic deities as these hymns are the victor’s recollection. This conciliation and integration (A) appear much more pragmatic and economic than abstract ideals (B) espoused by एकं सत् विप्रा बहुधा वदन्ति or other sophisticated thought from Upanishads or Gita. For B to emerge and sustain, A appears essential. With A established, B in some form or other would follow as evidenced by other Eastern faith systems which also tend to be inclusive. It is fair to say a combination of A and B lays the foundation for the emergence of quintessential pluralism of Hinduism.

Let us segway into a short story:

- In a village in Vengurla (South Konkan), there was a local Saint/Warrior (non-Brahmin) who was extremely popular with the masses.

- He passed away and his devotees wanted to make a shrine/temple for him. A Kaashyap Brahmin who was a respected man in the village objected. His objection stemmed from the deification of a man (probably Shudra) and placing him on the same pedestal as the Devas.

- The Brahmin (who had quite a bit of clout in the village) opposed this Adharma with all his might but was almost overpowered by the “uncouth masses” in the story.

- The landed or Kshatriya(ish) castes sided with the masses instead of the Brahmin and as a result, the Brahmin couldn’t prevent the deification.

- Additionally, the humiliated Brahmin was expected to condone the practice and give the shrine his blessings.

- He couldn’t be part of this Adharma and hence left his lands, wealth, position, and went northeast and settled in Ichalkaranji near Kolhapur preferring his descendants living in abject poverty over condoning Adharma.

- The replacement Gaargya Brahmin was happy to support the deification of the Saint. His descendants flourish economically in the village with large lands and respect but suffer spiritually.

- The shrine/temple remains popular to this day and most villagers have forgotten about this tale around the origin of that particular deity.

- The spiritual suffering of the current Brahmin was removed by the forgiveness of the descendent of the Kaashyap Brahmin some years ago.

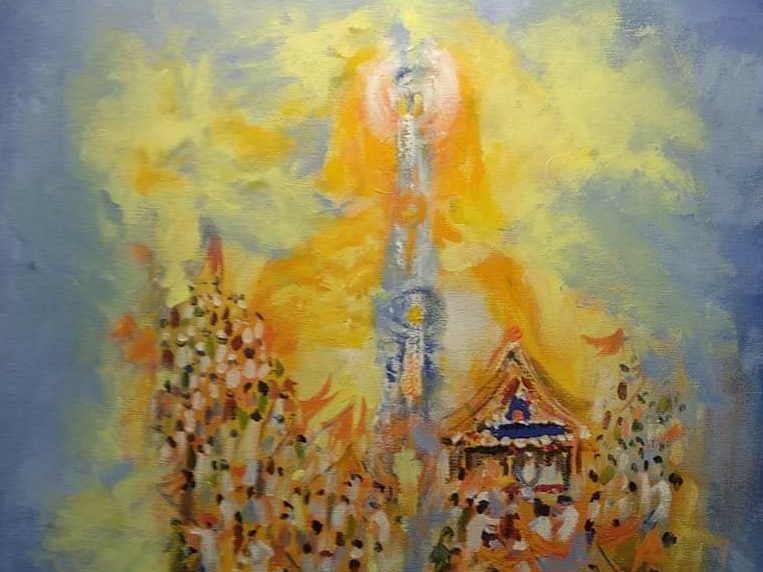

This is the fanciful tale of my great-great ancestor as told to me by my Chachera uncle (first cousin once removed). The Gotras are not important to this piece but the emphasis and obsession on Gotra is a salient feature of Brahmanism which deserves some attention. This tale is not very atypical. There have been other documented cases of such squabbles between village Hinduism and Brahmanism. This tale echoes many other tales from South Konkan – those of Ravalnath, Betal, etc. I am unsure if the deity in the tale of my ancestor is Ravalnath or Betal or something else entirely. But the contours of the tale are very similar. In both the cases of Ravalnath and Betal, there was initial resistance to these deities from local Brahmins in the medieval times – especially due to local traditions that involved blood sacrifices and other things frowned upon by Brahmins, but over time these deities got wider acceptance – even among local Brahmins.  While Ravalnath is a Kuladevata for most Goans (all castes), Betal is a Gramadevata of some local communities. Vithoba, the popular God of Pandharpur( the annual Waari) is a very important figure of the Bhakti movement. Religious scholar and Sahitya Akademi winner RC Dhere who extensively studied Vithoba also hypotheses pre Vedic origins of Vithoba. Khandoba is another deity whose origins are similarly muddy with a range of theories explaining him as the fusion of earlier deities including Kaal Bhairav. Interestingly in the Puranic tale of Kaal Bhairav “his struggle for the atonement of Brahmanhatya” is central. Khandhoba of Jejuri remains a deity for not only the Sudra castes, but Brahmins, Jains, Lingayats, and even some Muslims including the patronage of comparatively tolerant Bijapur Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah. While it would be tempting to dismiss this as some tenuous Donigerish take, the sheer numbers of such stories spread across the country strengthen the hypothesis.

While Ravalnath is a Kuladevata for most Goans (all castes), Betal is a Gramadevata of some local communities. Vithoba, the popular God of Pandharpur( the annual Waari) is a very important figure of the Bhakti movement. Religious scholar and Sahitya Akademi winner RC Dhere who extensively studied Vithoba also hypotheses pre Vedic origins of Vithoba. Khandoba is another deity whose origins are similarly muddy with a range of theories explaining him as the fusion of earlier deities including Kaal Bhairav. Interestingly in the Puranic tale of Kaal Bhairav “his struggle for the atonement of Brahmanhatya” is central. Khandhoba of Jejuri remains a deity for not only the Sudra castes, but Brahmins, Jains, Lingayats, and even some Muslims including the patronage of comparatively tolerant Bijapur Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah. While it would be tempting to dismiss this as some tenuous Donigerish take, the sheer numbers of such stories spread across the country strengthen the hypothesis.

Coming back to the descendants of the uncompromising Brahmin from Vengurla. Today my extended family proudly worships all the Gramadevatas from Ichalkaranji whose origins may be very similar to the one whose foundation my ancestor had objected to. Ironically most of my paternal family follow a plethora of local Saints (in addition to the popular Bhakti Saints), whose tales of the origin have occurred within living memory and hence are far easier to negate. I would not go into rants about these Saints (esp Gajanan Maharaj) whose followers number in millions. While some traditional elite Hindus (especially Urban) are known to have disparaging views of Saints & local deities, mostly these distinctions have weathered away. It is not unlikely to find Hindus who fast on Mondays for Shiva also fast on Thursdays for some local Saint (who mostly claim intellectual or avatarish descent from Dattatraya). Despite some initial friction, the Brahmanical thought has made its peace with such traditions. Most scholarship refers to this as – the local traditions (non-Vedic) being co-opted by Brahmanism. IMO this is an incomplete way of looking at it as it conflates organic integration which typically occurs over generations with the realization of some highly foresighted plan. Typically humans are not foresighted enough to pull off multi-generational machinations. From a multi-generation evolutionary paradigm, these would make sense but not if you take a snapshot at any particular moment in history.

With this background, we go into realms of pure speculation and come to the Post Vedic deities in Hinduism. The origin of some of these deities is highly contested – especially that of Shiva. While the Rgvedic Rudra is often said to be the precursor of Shiva, the meaning of Shiva is certainly in contrast with Rudra.  Whether the Pashupati seal from IVC or other Proto-Lingas are Proto-Shiva or not will likely not be resolved till we decipher the IVC script, but these speculations seem very plausible. Even Parpola doesn’t dismiss them in his Roots of Hinduism. In addition, Parpola makes a good argument in the IVC origins of Durga with seals of Tiger riding goddesses from Kalibangan. Similarly, we can say the Dravidian Murukan and the Vedic Skanda gave rise to the Karthikeya we know today. We still don’t have any intelligent speculation about the origins of Ganesha (other than some references to Gajapati), buts it fair to assume the elephant-headed god is a pretty late addition to the Hindu pantheon. The aim here is not to discuss and speculate the origins of these deities but to guess the mechanisms of integration of these deities and customs into Brahmanism. Brahmins had a huge ritualistic/moral capital, but given the tenuous or conflicting relations they had with the Kshatriyas and other dominant castes (as seen through numerous puranic stories especially those of Parshuram) it is fair to assume Brahmins would not often get their way with subtracting traditions they found Adharmic or uncouth, yet they could continue to shape these traditions from inside with participation. Pressure both from the masses and Brahmins would’ve actively shaped the integration of these traditions for centuries to the point where it’s often hazy where Brahmanism ends and where “Non-Brahmanical” traditions begin. (This probably happened with Sramana or Proto-Sramana traditions competing with Brahmanism but that is a different discussion)

Whether the Pashupati seal from IVC or other Proto-Lingas are Proto-Shiva or not will likely not be resolved till we decipher the IVC script, but these speculations seem very plausible. Even Parpola doesn’t dismiss them in his Roots of Hinduism. In addition, Parpola makes a good argument in the IVC origins of Durga with seals of Tiger riding goddesses from Kalibangan. Similarly, we can say the Dravidian Murukan and the Vedic Skanda gave rise to the Karthikeya we know today. We still don’t have any intelligent speculation about the origins of Ganesha (other than some references to Gajapati), buts it fair to assume the elephant-headed god is a pretty late addition to the Hindu pantheon. The aim here is not to discuss and speculate the origins of these deities but to guess the mechanisms of integration of these deities and customs into Brahmanism. Brahmins had a huge ritualistic/moral capital, but given the tenuous or conflicting relations they had with the Kshatriyas and other dominant castes (as seen through numerous puranic stories especially those of Parshuram) it is fair to assume Brahmins would not often get their way with subtracting traditions they found Adharmic or uncouth, yet they could continue to shape these traditions from inside with participation. Pressure both from the masses and Brahmins would’ve actively shaped the integration of these traditions for centuries to the point where it’s often hazy where Brahmanism ends and where “Non-Brahmanical” traditions begin. (This probably happened with Sramana or Proto-Sramana traditions competing with Brahmanism but that is a different discussion)

While it is generally said Brahmanical thought absorbed the local traditions, it is equally or more appropriate to say that the village Hinduism made space for Brahmanism & tamed it – into the diverse and plural fold and this process was not complete for the entire subcontinent when Mahmud of Ghazni attacked Somnath. Scholars like to emphasize Adi-Shankara’s Advaita and Mutts, Upanishads, Rgvedic “एकं सत् विप्रा बहुधा वदन्ति” as it appears sophisticated and intellectual. However, the tendency of humans to pragmatically negotiate the boundaries of their traditions (in absence of exclusionary universalist ideas) when they already have multiple modes of worship tends to be underemphasized as it appears uncouth or folk. Roman religion easily absorbed Isis and Cybele into the Roman fold but couldn’t absorb the God of Abraham. In contrast, when Christianity conquered Europe it absorbed the old gods into the Christian fold as Saints but kept them subordinate to the one true god. However, Shiva and Ganesh did not bow done to Indra, and by the time of the Puranas, the mighty Vedic Indra was reduced to an insecure and somewhat petty King of Gods.

Maybe the Brahmin elites & Sanskrit managed to maintain a cohesive identity-based on sacred geography only because they themselves were tamed in similar mechanisms by the natives of the geography. If yes, then Hindu Pluralism and Syncretism is as much a legacy of numerous lost stories as it is of the philosophical moorings of the Vedas, Itihasas, and Upanishads.

Postscript:

I had been thinking along these lines since my discussion with Mukunda and Omar on the Brown-cast about the roots of Indian pluralism. While commenting please stick to the topic and be civil & constructive. I will delete off comments for this piece.