I’m reading Ben Keirnan’s Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. I picked it up mostly because over half the book does not consist of the history of the Vietnam War (a major failing I’ve noticed with books which are histories of Vietnam, as opposed to histories of Vietnamese-American relations).

I’m reading Ben Keirnan’s Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. I picked it up mostly because over half the book does not consist of the history of the Vietnam War (a major failing I’ve noticed with books which are histories of Vietnam, as opposed to histories of Vietnamese-American relations).

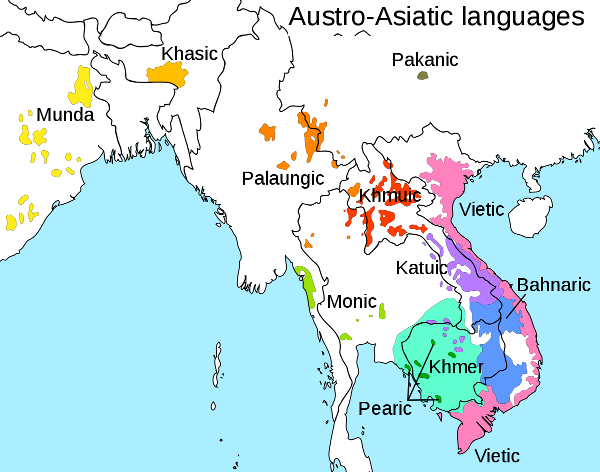

The section on Austro-Asiatic languages (Vietnamese is one) has something of relevance to the “Munda question”. But before that, let me review a few things.

Until very recently many historians and prehistorians of India have suggested that the Munda people, who speak very distinctive dialects related to the Austro-Asiatic languages of Southeast Asia, are the primal people. That is, they are the aboriginals. The original adivasis.

I do not believe that this case is tenable. Because I am a geneticist, I make this judgment on genetic grounds. Chaubey et al., Population Genetic Structure in Indian Austroasiatic Speakers: The Role of Landscape Barriers and Sex-Specific Admixture, reveals what we know about the genome-wide patterns in the Munda.

1) They are highly enriched for East Asian ancestry compared to other South Asians.

2) Many Munda males carry a haplogroup, O-K18 (once O2a), that is very common in Southeast Asia, especially Austro-Asiatic groups. Additionally, it is more diverse in Southeast Asia. The Munda O-K18 branch seems to be a side shoot from the broader Southeast Asian tree.

3) The Munda mtDNA, defining the maternal line, is uniformly South Asian. This is in contrast to the situation with Bengalis, who have East Asia Y and mtDNA. This indicates that the Munda migration was heavily male-mediated.

4) The Munda carry mutations in genes that are associated with recent selective sweeps in East Asians (e.g., on the EDAR locus). Though this may be a parallelism, it’s unlikely. Rather, it is through shared common descent that this occurs.

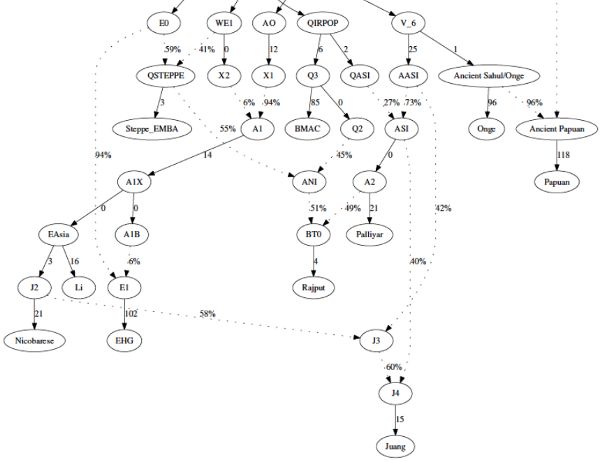

The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia has a graph which shows population relationships and gene flow that illustrates important aspects of the Munda ethnogenesis (Juang below):

AASI in this model = Ancient Ancestral South Indians. These are very distantly related to Andaman Islanders, Australo-Melanesian Southeast Asians, and more distantly to eastern Eurasians generally. They are likely aboriginal people to South Asia, with no West Eurasian ancestry.

The model above indicates that an East Asian (Austro-Asiatic) population encountered an AASI population and produced a daughter population. Then, that daughter population mixed with an ASI population, ASI being an old and stable mix of West Eurasian Iranian farmer (~25%) and AASI (75%).

This means two things for the Munda. First, they are very AASI enriched. This is obvious in any analysis. And, their West Eurasian ancestry is almost all Iranian farmer and not steppe. This is totally not surprising either. Using more naive model-based clustering Munda samples always seem to lack the components which are most easily adduced to be Indo-Aryan. They have very low frequencies of Y haplogroup R1a1a-Z93.

Let’s take a step back now. The fact that the Austro-Asiatic males arrived when there were unmixed AASI indicates that this was somewhat early. There are no unmixed AASI on the Indian subcontinent today. When we reach the Iron Age, by 500 BCE it is clear that Indo-Aryan society had pushed at least to Bihar. This component would bring steppe ancestry, as well as mixing into any remnant AASI.

So when could the Austro-Asiatics have arrived at the earliest? Two papers with extensive ancient DNA, Ancient genomes document multiple

waves of migratin in Southeast Asian prehistory and The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia give us a good sense. It seems that the expansion of Austro-Asiatic farmers dates to about 4,000 years ago. That is when the transition seems to occur in northern Vietnam.

One thing that is also evident: the East Asian gene flow into the Munda seems to come from northern Austro-Asiatic groups in Thailand, not the southern branch which resulted in the people of the Nicobar Islands and was eventually submerged by Austronesians. On a final note, a site in northern Burma yielded an individual who was clearly Tibeto-Burman, and not Austro-Asiatic, 3,000 years ago. So even at that date mainland Southeast Asia was heterogeneous.

But, considering that there is no evidence of Tibeto-Burman ancestry Munda, whose Austro-Asiatic ancestry seems to have come through Burma through a mainland route (as opposed to up from maritime Southeast Asia), I think one should push the date of their arrival before 1000 BCE. With the expansion of farming in mainland Southeast Asia at around ~4,000 years ago, that puts the arrival of a distinctive Munda culture in South Asia to between 2000BCE and 1000 BCE. It is entirely reasonable that during this period there were unmixed AASI in eastern South Asia, though the admixture graph may also be picking up assimilation Austro-Melanesian ancestry in southern China/Southeast Asia.

This is where Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present comes in: the author suggests that the early Austro-Asiatic farmers were dry-land rice farmers who occupied uplands. The reason being that reconstructed Austro-Asiatic common words for rice culture is indicative of dry-land practices, with later wet-rice terminology often being borrowings from Tai and Austronesians.

I don’t know enough Indian archaeology and agricultural history to comment further, but, a visual inspection of where Munda are concentrated does suggest upland farming….