was reported missing, the I.D.F. enacted the Hannibal Directive….“No soldier will be kidnapped….he has to detonate

his own grenade along with those who try to capture him…..his unit will now have to fire at the getaway car”…..

…

…..

So…who is this Hannibal of Carthage (after whom the Hannibal Directive is named) who drank poison rather than be captured by Romans?

…..

……

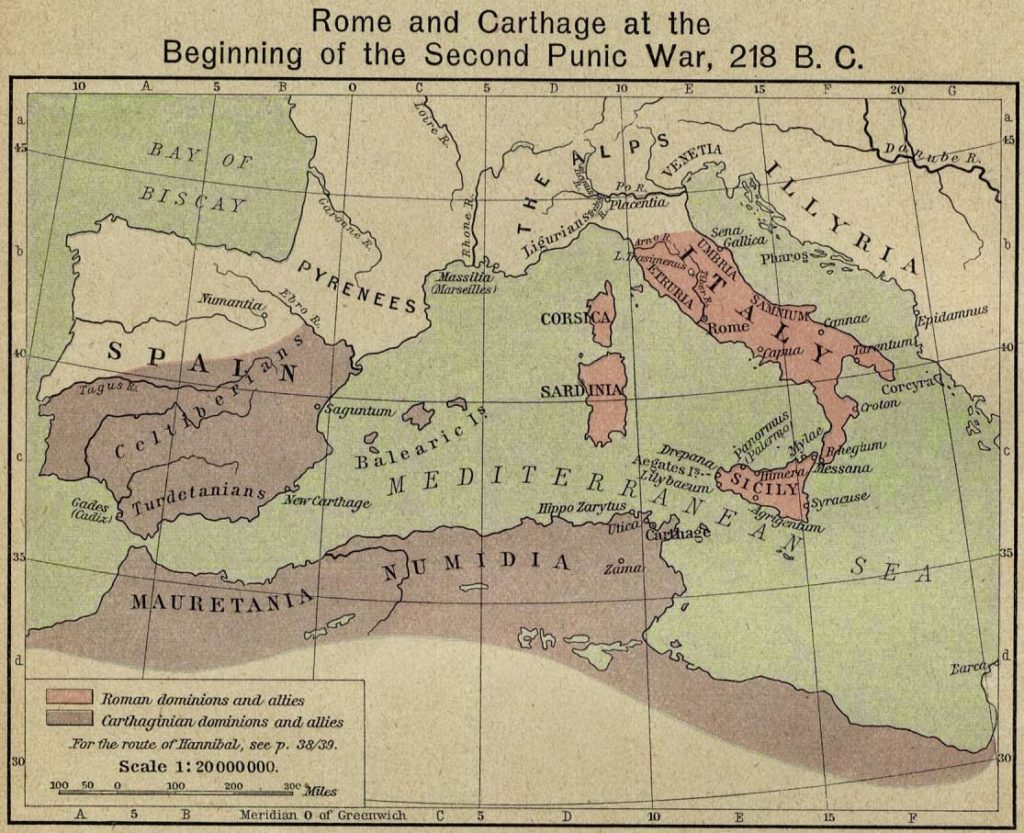

Hannibal, son of Hamilcar Barca (247 – 183/182/181 BC) was a Punic Carthaginian military commander, generally considered one of the greatest military commanders in history. His father, Hamilcar Barca, was the leading Carthaginian commander during the First Punic War.

…

Hannibal lived during a period of great tension in the Mediterranean, when the Roman Republic established its supremacy over other great powers such as Carthage, the Hellenistic kingdoms of Macedon, Syracuse, and the Seleucid empire.

…..

One of his most famous achievements was at the outbreak of the Second Punic War, when he marched an army, which included elephants, from Iberia over the Pyrenees and the Alps into northern Italy.

……..

After the war, Hannibal … fled into voluntary exile. During this time, he lived at the Seleucid court, where he acted as military advisor to Antiochus III in his war against Rome. After Antiochus met defeat at the Battle of Magnesia and was forced to accept Rome’s terms, Hannibal fled again, making a stop in Armenia.

….

His flight ended in the court of Bithynia, where he achieved an outstanding naval victory against a fleet from Pergamon. He was afterwards betrayed to the Romans and committed suicide by poisoning himself.

……

Buried deep inside a Times report

last weekend about Hadar Goldin, the Israeli soldier who was reported

captured by Hamas, in the southern Gaza Strip, and then declared dead,

was the following paragraph:

The circumstances

surrounding his death remained cloudy. A military spokeswoman declined

to say whether Lieutenant Goldin had been killed along with two comrades

by a suicide bomb one of the militants exploded, or later by Israel’s

assault on the area to hunt for him; she also refused to answer whether

his remains had been recovered.

Just

what those circumstances were began to filter out early this week, and

they attest to deep contradictions in the Israeli military—and in

Israeli culture at large.

A

temporary ceasefire went into effect last Friday morning at eight. At

nine-fifteen, soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces headed toward a

house, in the city of Rafah, that served as an entry point to a tunnel

reportedly leading into Israel.

As the I.D.F. troops advanced, a Hamas

militant emerged from the tunnel and opened fire. Two soldiers were

killed. A third, Goldin, was captured—whether dead or alive is

unclear—and taken into the tunnel.

What is clear is that after Goldin

was reported missing, the I.D.F. enacted a highly controversial measure

known as the Hannibal Directive, firing at the area where Goldin was

last seen in order to stop Hamas from taking him captive. As a result,

according to Palestinian sources, seventy Palestinians were killed. By

Sunday, Goldin, too, had been declared dead.

Opinions differ over

how this protocol, which remained a military secret until 2003, came to

be known as Hannibal. There are indications that it was named for the

Carthaginian general, who chose to poison himself rather than fall

captive to the Romans, but I.D.F. officials insist that a computer

generated the name at random. Whatever its provenance, the moniker seems

chillingly apt.

Developed by three senior I.D.F. commanders, in 1986,

following the capture of two Israeli soldiers by Hezbollah, the

directive established the steps the military must take in the event of a

soldier’s abduction. Its stated goal is to prevent Israeli troops from

falling into enemy hands, “even at the cost of hurting or wounding our

soldiers.”

…

While normal I.D.F. procedures forbid soldiers from firing in

the general direction of their fellow-troops, including attacking a

getaway vehicle, such procedures, according to the Hannibal Directive,

are to be waived in the case of an abduction: “Everything must be done

to stop the vehicle and prevent it from escaping.”

……

Although the

order specifies that only selective light-arms fire should be used in

such cases, the message behind it is resounding. When a soldier has been

abducted, not only are all targets legitimate—including, as we saw over

the weekend, ambulances—but it’s permissible, and even implicitly

advisable, for soldiers to fire on their own.

………

For more than a decade,

military censors blocked journalists from reporting on the protocol,

apparently because they feared it would demoralize the Israeli public.

In 2003, an Israeli doctor who had heard of the directive while serving

as a reservist, in Lebanon, began advocating for its annulment, leading

to its declassification. That year, a Haaretz investigation

of the directive concluded that “from the point of view of the army, a

dead soldier is better than a captive soldier who himself suffers and

forces the state to release thousands of captives in order to obtain his

release.”

…….

For years, Israeli soldiers on the battlefield had

hotly debated the directive and its use. At least one battalion

commander, according to the Haaretz investigation, refused to

brief his soldiers on it, arguing that it was “flagrantly illegal.” And a

rabbi, asked by a soldier about the order’s religious aspect, advised

him to disobey it.

…….

Major General Yossi Peled, one of the commanders who

drafted the directive, told Haaretz that its purpose was to

assert how far the military could go to prevent abductions. “I wouldn’t

drop a one-ton bomb on the vehicle, but I would hit it with a tank shell

that could make a big hole in the vehicle, which would make it possible

for anyone who was not hit directly—if the vehicle did not blow up—to

emerge in one piece,” Peled said. It’s understandable that soldiers

would scratch their heads over formulations such as these.

……….

To be

clear, there is no evidence that Goldin was killed by friendly fire. But

military officials did confirm that commanders on the ground had

activated the Hannibal Directive and ordered “massive fire”—not for the

first time since Operation Protective Edge began, on July 8th. (One week

into the ground offensive, in the central Gaza Strip, forces reportedly enacted

the protocol when another soldier, Guy Levy, was believed missing.)

……

Since the directive’s inception, the I.D.F. is known to have used it

only a handful of times, including in the case of Gilad Shalit. The

order came too late for Shalit and did not prevent his abduction—or his

eventual release, in 2011, in exchange for a thousand and twenty-seven

Palestinian prisoners.

…….

That year, as part of the military’s inquiry into

the circumstances leading to Shalit’s capture, the I.D.F.’s Chief of

Staff, Benny Gantz, modified the directive. It now allows field

commanders to act without awaiting confirmation from their superiors; at

the same time, the directive’s language was tempered to make clear that

it does not call for the willful killing of captured soldiers. In

changing the wording of the protocol, Gantz introduced an ethical

principle known as the “double-effect doctrine,” which states that a bad

result (the killing of a captive soldier) is morally permissible only

as a side effect of promoting a good action (stopping his captors).

……..

Whether

soldiers have heeded this change in language, and how they now choose

to interpret the directive, is difficult to assess. If past experience

is any indication, the military hierarchy’s interpretation remains

unequivocal. During Israel’s last operation in Gaza, in 2011, one Golani

commander was caught on tape telling

his unit: “No soldier in the 51st Battalion will be kidnapped, at any

price or under any condition. Even if it means that he has to detonate

his own grenade along with those who try to capture him. Even if it

means that his unit will now have to fire at the getaway car.”

………..

On Sunday, a decade after its initial investigation of the Hannibal Directive, Haaretz revisited the subject with a piece

by Anshel Pfeffer that tried to explain why, despite the procedure’s

morally questionable nature, there hasn’t been significant opposition to

it. Pfeffer wrote:

Perhaps the most deeply engrained

reason that Israelis innately understand the needs for the Hannibal

Directive is the military ethos of never leaving wounded men on the

battlefield, which became the spirit following the War of Independence,

when hideously mutilated bodies of Israeli soldiers were recovered. So

Hannibal has stayed a fact of military life and the directive activated

more than once during this current campaign.

Ronen

Bergman, author of the book “By Any Means Necessary,” which examines

Israel’s history of dealing with captive soldiers, further explained

this rationale in a recent radio interview:

“There is a disproportionate sensitivity among Israelis [on the issue

of captive soldiers] that is hard to describe to foreigners.” Bergman

traced this sensitivity back to Maimonides, the medieval Torah scholar,

who wrote: “There is no greater Mitzvah than redeeming captives.”

….

This

line of argument, while historically true, is worth pausing over—if

only to unpack the moral paradox within it. In essence, what this

“military ethos” means is that Israel sanctifies the lives of its

soldiers so much, and would be willing to pay such an exorbitant price

for their release, that it will do everything in its power to prevent

such a scenario—including putting those same soldiers’ lives at

risk (not to mention wreaking havoc on the surrounding population).

…….

This

is the dubious situation that Israel finds itself in: signalling to the

military that a dead soldier is preferable to a captive one, while at

the same time signalling to the Israeli public that no cost will be

spared to secure a captured soldier’s release. (It’s worth recalling

that, three years after Shalit was traded for more than a thousand

Palestinian prisoners, the captive U.S. Army Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl was

traded for five Taliban prisoners. This isn’t to suggest that Israel

cares more about its troops than the United States does, but rather that

no crime is greater, in the eyes of Israelis, than the kidnapping of

“our boys.”)

….

Daniel Nisman, who runs a geopolitical-security consultancy, told the Times that

the Hannibal Directive “sounds terrible, but you have to consider it

within the framework of the Shalit deal. That was five years of torment

for this country, where every newscast would end with how many days

Shalit had been in captivity. It’s like a wound that just never heals.”

….

On

Tuesday, as a seventy-two-hour ceasefire went into effect and the

I.D.F. pulled its ground forces out of Gaza, I spoke to Assaf Sharon,

the academic director of Molad, a progressive Israeli think tank that

focusses on social policy. While he accepted Nisman’s logic, he

questioned the Hannibal Directive’s social ramifications. “I don’t know

that you can draft clear-cut rules that would apply to any situation,

but I do think that a certain risk of a captured soldier’s life should

be allowed. I think the real problem starts with the hysterical

discourse, of the kind that says, ‘This must be stopped at any cost.’

…..

From there, the path to the horrors we’ve seen over the last few days,

in Rafah, is a short one. What we’ve seen wasn’t only putting a

soldier’s life at risk but intentionally targeting anything that

moved—whether relevant or irrelevant.”

…

Sharon added that the

mixed consequences of the directive are typical of the behavior that now

characterizes the Israeli public at large. “On the one hand, we are

willing to risk soldiers’ lives recklessly and without need, but on the

other hand we have zero tolerance for the price that this might entail.”

…

With

sixty-seven Israelis and more than eighteen hundred Palestinians

killed, ground forces have completed their withdrawal from the Gaza

Strip. The Hannibal Directive will soon be tucked away, along with the

worn bulletproof vests, until the next time the military wades into

hostile territory. But its moral implications will linger. It’s time for

the painful reconstruction, both in Gaza and in Israeli society, to

slowly start.

….

Link: http://www.newyorker.com/hadar-goldin-hannibal-directive

…..

regards