Farewell, Houston

I arrived in Houston because of an email. I had just gotten done with my USMLE step one in July 2016 and was furiously emailing people in the U.S. for possible observer-ship opportunities. I did not get a lot of replies. Almost a week after I had started this process, I got an email from a famous pathologist at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDA) in Houston. It was brief and to the point. He wrote that he can accommodate me next year in April. I was over the moon. Prior to this episode, I had never been to Houston or known anyone from the city, except a professor of history at Rice University.

I arrived in Houston in April 2017 after spending some time doing observer-ships and studying for USMLE step two, in West Virginia and Miami. It wasn’t as hot as I had expected it to be and in my initial encounters, I found people to be generally friendly and warm. Houston wasn’t culturally impenetrable as Miami or as distant as West Virginia. It was a city teeming with people who looked like me, with huge hospitals and endless roadways. I had booked an Airbnb for my first two weeks of stay and then moved to a private room I had rented from a very interesting character named Gustavo (Gus). I met Gus through a random mutual friend on Facebook, a Pakistan-American girl who had added me as a friend after some of my work on environmental issues in Pakistan. She was renting from Gus at a different location and got me in contact with him. I spent two months at MDA, left for three weeks to visit Pakistan, and returned to the Houston area. While I was at MDA, I met a resident from the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston who got me intrigued about the program and I met the Chair of the program who was welcoming. Afterward, I was in Galveston for the next three years, firstly to do research or get observer-ship at the medical school there (didn’t get either) and later, for residency training at the same medical school. Two years into my residency (total of four years), we moved to the clear lake/NASA suburb of Houston, and another two years afterward, out of Houston for good, for my fellowship.

It was a tough decision to leave but after a lot of brainstorming and weighing options, I felt it best to leave the area. There were many things that I like in Houston and a lot more that I disliked. Following is a brief discussion of both.

Things I will miss about Houston/Texas

Food/”Shef”/Diversity

Houston has been ranked as the fourth most diverse city in the United States. According to some data that I’ve seen, there are more Pakistanis living in Houston metro area than anywhere else in the US. A lot of Vietnamese refugees during the 1970s settled there and the Hispanic community has always had a foothold in the city. I remember once interacting with people from nine nationalities in a single day while I was at MD Anderson. As with other diverse places, I didn’t find many regional/national ghettos in the metro area. However, there are places with more people of one ethnicity than another; with an abundance of Desis in Sugarland, same in the Chinatown area but you can find different ethnicities almost everywhere in the city.

Mahatma Gandhi district/Hillcroft Avenue offers some of the best Indian/Pakistani restaurants in the country. I will certainly miss the Halwa puri, chaat options, and Indian vegetarian food available in the area. A year or so ago, I found out about a food service where you can order home-cooked food from local chefs, called “Shef”. I availed myself of that service every week and had some delicious food without having to cook it myself. Shef is available only in a few cities in the U.S. (NYC, San Francisco, L.A, Houston, and D.C. as far as I’ve checked) and I will sorely miss the time it saved me and the variety of Indian food that I could taste at a great cost.

There were also many “fusion” foods that chefs created because of diverse cultures. Halal southern hot chicken sandwiches and Texan-Vietnamese tacos were just two examples.

Another example of diversity was a halal grocery store in the same shopping plaza as “battle rifle company”.

Organized medicine

One of my friends in Miami told me before I arrive in Houston that Texas is a great place for doctors to live and work. I did not know what she meant and didn’t press her to explain why. Many years later, I understand what she meant. It was not just about average salaries or jobs, both of which are plentiful in Texas. It has to do with tort reform in the state that was enacted in the early 2000s after long-term advocacy by Texas physicians. I had the unique opportunity to interact and work with some of the people who worked behind the scenes at the time advocating for tort reform.

I got my first taste of organized medicine through the Texas Society of Pathologists (TSP). I started off as a liaison from TSP to my program and eventually ended up being Chair of a committee and being on other committees. TSP is the oldest pathology society in the US (established 1921) and is also the most active state society in the field. TSP works under the umbrella of the Texas Medical Association (TMA). TMA has more than 55000 members including medical students, trainees, and licensed physicians. TMA was responsible for getting tort reform enacted in the state because residents were leaving the state after training in droves because of high liability insurance rates in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

TMA is a behemoth with millions of dollars in assets, lobbyists in Austin, a liability insurance trust, and a foundation that gives away millions of dollars to deserving medical students across the state. TMA also gives out educational loans to medical students and residents at very low-interest rates. I was part of the Resident-Fellow section and served on the board of the TMA foundation for a year, followed by a year of the TMA board of trustees. During my time on the board of trustees, physicians in Texas faced unprecedented challenges such as Texas laws S.B. 6 and S.B.8 and a national dispute over the “No Surprises Act” for which TMA sued the HHS.

The house of medicine is under assault from many sides. Right-wing assault on reproductive care, private equity eating up hospitals, encroachment from extender services like physician assistants and nurse practitioners (called “scope of practice”), and Medicare cuts are some of the highlights. TMA is involved in fighting all of these, on a state and national level.

Things I will NOT miss about Houston/Texas

The weather

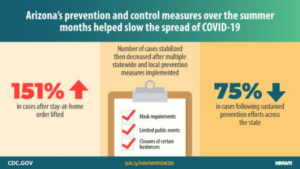

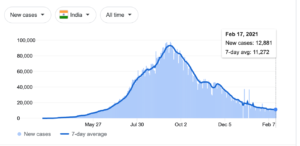

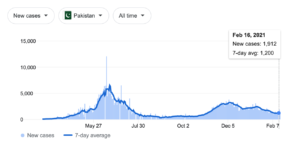

Before I arrived in Galveston, my professor friend from Rice had warned me about hurricanes. Galveston Island was decimated by “The Great Storm” of 1900 and the whole city had to be rebuilt. Since then, other hurricanes have affected Galveston, the most recent being “Ike” whose storm surge flooded the island, at some points reaching six feet in height. My friend’s prophecy almost came true in August 2017 with Hurricane Harvey, but instead of Galveston, it caused massive flooding in Houston. Since then, I became an amateur meteorologist between June 1st and late October (hurricane season) every year, trying to discern which tropical disturbance could affect us when. We had some near misses in the last few years until there was a snow storm in February 2021, which caused blackouts, reminding me of Pakistan.

Even besides the hurricane season, Houston’s weather was frustrating at best. On January 1st, 2022, it was 80 degrees in the afternoon, dropping to 35 degrees at midnight. Houston weather resembled Lahore weather quite a lot, with humidity as the cherry on top. It could be 80 degrees with a real feel of 103 because of humidity. Even A.Cs don’t work above a certain temperature. Last year, between July and September, our central A.C. couldn’t cool off during the last few hours of the day and we were stuck between 73 and 78 degrees until late at night. The temperature started soaring in late May and days would be hot and humid till December. And it is only getting worse with climate change. A friend recently posted on Facebook that “Texas is that feeling when you open the oven to check on your cookies and you burn your face. Only there are no cookies and you can’t shut the oven door”. Just as I was writing this, saw this headline: “Extreme heat pushes highs over 110 in Texas as power grid nears brink”.

Urban Sprawl

Harris County, with Houston as its main city, has a larger population than more than 30 states in the U.S. Houston is second only to Dallas in terms of cars per household in the U.S. as well. Combine these two facts with the never-ending expressways and you have a city in which you have to drive at least 30 minutes to go anywhere. I remember carpooling with a guy once who drove from his house in the Northern part of Houston to Galveston (almost a two-hour journey) starting at 4:30 am. He would leave Galveston in the late afternoon to get home by 6:30 pm. This is not a typical drive in the area but many people I knew (including myself) had long commutes every day. Texas is mostly flat so all you get along your drive are strip malls and gas stations. As a result, greenhouse gases generated on Texas roads account for 0.5 percent of total worldwide carbon dioxide emissions, even as the state accounts for 0.38 percent of the world’s population. The only good thing about roads in Houston are the feeder roads, so if you miss an exit, you can take the next one and turn around.

For anyone more interested in reading about Houston’s infrastructure issues and history, Stephen Klineberg’s book “Prophetic City: Houston on the cusp of change in America” is an excellent read.

An imaginative take on Texas roadways in the Texas Observer: https://www.texasobserver.org/the-road-home/

Politics

Texas is second only to California in terms of residents. As the saying goes, everything is big in Texas. That includes the disregard that politicians have for their constituents. The late great Molly Ivins, one of my favorite Texans of all time, once wrote this about the Texas legislature: “As they say around the Texas Legislature, “If you can’t drink their whiskey, screw their women, take their money, and vote against ’em anyway, you don’t belong in office”. A friend of mine from Lahore once called and asked how Texas treated people. He was intrigued because he had read in the news that a lot of businesses were moving their HQs to Texas. I told him that if you are not a straight, white, Christian man with a small business in the state of Texas, the state government doesn’t care if you live or die.

Texas lags behind on all key indicators of education, healthcare (despite it being so good for doctors), nutrition, and income inequality compared to other big states in the union. There are more uninsured people in the state than anywhere else because Texas politicians refuse to expand Medicaid and impose work requirements on the poorest people. Maternal mortality rates are even lower than the national average. Texas’s power grid is not connected to the national grid, which makes a great advertisement for “doing it all alone” but is a terrible idea in a state so prone to natural disasters. The level of corruption in Texas has been phenomenal over the years, regardless of which party was in power (another one of my all-time favorites, LBJ was an emblem of that). Because of constant gerrymandering, one party has been permanently in power for the last two decades and will be, for the foreseeable future. Even Beto (who has his faults) couldn’t defeat one of the most hated men in the country in Texas. While moving away from a place that has different politics than yours is not always possible or beneficial, I found the political climate to be smothering.

I could live with the monster trucks with “Infowars” stickers at our local grocery stores or people I played pickleball with wearing NRA shirts or our one-time neigAbdulhbors who stopped interacting with us as soon as they saw the color of my skin but I couldn’t live with S.B. 8 (the vigilante law) or the Billboards along highways congratulating Texas with a picture of multiple babies as soon as Roe was repealed or when a bigwig in TMA boasted about hosting Greg Abbot at their house for a fundraiser.

For a good review of Texas’s political history and impending future, Lawrence Wright’s “God Save Texas: A journey into the soul of the lone star state” is highly recommended.

Will I ever go back to Texas?

I have been asked this question by friends and acquaintances many times since I decided to leave. As of now, my answer is a firm “No”. I may visit occasionally for a conference or to visit my residency program but I don’t see why I would want to live in Texas if I have the choice. My life was changed completely while I was there and I am thankful for many things that happened when I was there, friends that I made and spent time with, meals that I cherished but also, heartbreak and forgettable memories.

P.S: The astronauts originally said: Houston we have had a problem.

I don’t personally know Ammar Rashid, but I know many people like him and many people who either went to school with him or moved in the same circles. Unlike many (most?) Pakistani students who study abroad and develop a deep understanding of the mess that is Pakistan, Ammar Rashid chose to return to his country. He lives his life according to what he believes in (no matter how unpopular those beliefs and ideas may be), and not a lot of people in Pakistan can say that. I heard

I don’t personally know Ammar Rashid, but I know many people like him and many people who either went to school with him or moved in the same circles. Unlike many (most?) Pakistani students who study abroad and develop a deep understanding of the mess that is Pakistan, Ammar Rashid chose to return to his country. He lives his life according to what he believes in (no matter how unpopular those beliefs and ideas may be), and not a lot of people in Pakistan can say that. I heard