Note: This post first appeared on Internet Stuff. You can read it here.

Rajaji: Our forgotten hero

In the run up to Indian parliamentary elections in 2024, there is excitement in some sections of social media about “freemarket” ideas espoused by C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) and the Swantantra Party he helped found in 1959.

Sharing a piece here I wrote on Rajaji’s ideological relevance in contemporary politics. This was written after visiting and reporting from the many institutions he built pre and post 1947 for the now defunct Pragati Magazine in 2018.

You can follow me here.

And the food-and-agriculture-focussed independent media platform called the ThePlate.in I run.

Here goes…

Rajaji: Our Forgotten Hero

Among the leaders in the front ranks of the freedom movement, and those counted as the makers of modern India, Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) is perhaps the man most forgotten. Gandhi is the ‘Father of the nation’; the very existence of India as a modern democracy, and lately all its faults—from clogged drains to currency fluctuation—are credited to Jawaharlal Nehru’s side of the ledger; the race to usurp Vallabhbhai Patel’s legacy has given India a Guinness record for the world’s tallest statue; Bhimrao Ambedkar is not only a Moses-like lawgiver who framed the constitution but also the messiah of marginalized; Maulana Azad, now firmly located in Indian-Muslim politics, finds an occasional ode to his prescience about the fallacy of Pakistan and subsequent fate of subcontinental Muslims. Rajaji is less lucky than Azad. Continue reading Rajaji: Our forgotten hero

From Udaipur to Okinawa riding on orange peel

The story of twenty-five -year-old Narayan Lal Gurjar might not be out of place in Bollywood.

The playful experiments he conducted in his father’s small farm as a teenager in Kerdi, a village of 300 with 40 homes in Rajsamand district in southern Rajasthan, is the foundation for his patents and the agriscience startup incubated by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology that has attracted investments from well-known Japanese venture capital firms such as Beyond Next Ventures and MTG.

And all this before he turned 23.

Gurjar’s firm EF Polymer (EF stands for eco-friendly) headquartered in Okinawa with manufacturing plants in Udaipur makes super absorbent polymers (SAP) from orange and banana peel that has the potential to help millions of small farmers in arid and water scarce regions across the world harvest better yields.

Read the full story here

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/

The Caped Crusader

TW: This post contains descriptions of suicide.

Guru Dutt’s 1957 classic Pyaasa is about a disillusioned poet who is aghast at how people treat fellow humans in their pursuit of wealth, lust and power. In the iconic ending monologue, Dutt clarifies that he has no complaints against his friends, brothers and all the others who ill-treated him. His problem is with the structure of society, which peels away the humanity from humans.

19-year-old Abraham Biggs from Florida, USA was a regular on messaging board BodyBuilding.com. Apart from threads dedicated to diet, exercise, powerlifting, etc., there was a miscellaneous section on the site for random discussions not particularly related to bodybuilding. Predictably, this became the light-hearted section of the site- memes, jokes and banter flowed freely.

At 2:35 AM on November 19, 2008, Biggs posted a thread- he was going to commit suicide while livestreaming on Justin.tv, a streaming site and a precursor to Twitch. This was not the first time Biggs was talking about his mental health – he had started another thread in December 2007 about feeling down and how he had attempted to take his life earlier.

Biggs had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and had been taking prescription medication for it. His plan was to overdose on the meds.

Disgustingly, the comments on his stream were goading him on, or calling the whole thing a hoax.

A 17-year-old regular of the site (username: “Bulker”) chanced upon the thread, and clicked through to the livestream. Bulker was alarmed to see what was happening. He had interacted with Abraham on the site before, and felt compelled to act. The problem was, he was at the other end of the world- in India. He did some quick online sleuthing and found Abraham’s name, number, approximate address and pictures. He posted these details, and even updated Miami police contact details on the thread, begging US folks to do something. But no one did.

This was the bystander effect at play. Like people gawk at traffic accidents but don’t do anything about it if there are other people around. They just assume that someone from the crowd must’ve already taken action, like alerting the authorities. This effect was first identified in the murder of Kitty Genovese.

Bulker realised no one was going to act. He tried emailing Miami police but the mail bounced. He snuck into his parents’ bedroom and accessed his mother’s phone. After activating the exorbitantly expensive international calling plan, he called Miami police and tried to explain the situation. He kept getting transferred around and he had to explain over and over again. The clock was ticking, his calling minutes were running out and he couldn’t make any headway, except to locate Abraham’s exact jurisdiction and which sheriff to contact. He posted this information too on the forum. Someone finally realised the seriousness of the matter, and called the sheriff. Minutes later, Bulker too got in touch with him- he had now activated international minutes on his father’s phone. The sheriff reassured him that they had already received multiple calls and help was on the way.

Police arrived at the scene about 15 minutes later. It was 3 PM in Florida and 1:30 AM in India. On the livestream, they were first seen throwing something towards Abraham, and when he didn’t respond, they entered the room, checked his body and then covered the camera. Abraham Biggs had already passed.

This incident affected Bulker deeply. He got involved in social work, first in Gujarat and then Bengaluru, where he moved to in 2016. He volunteered during the COVID pandemic, and was able to get acquainted with the city police commissioner, who encouraged him to get more involved in public issues and act as an interface with authorities.

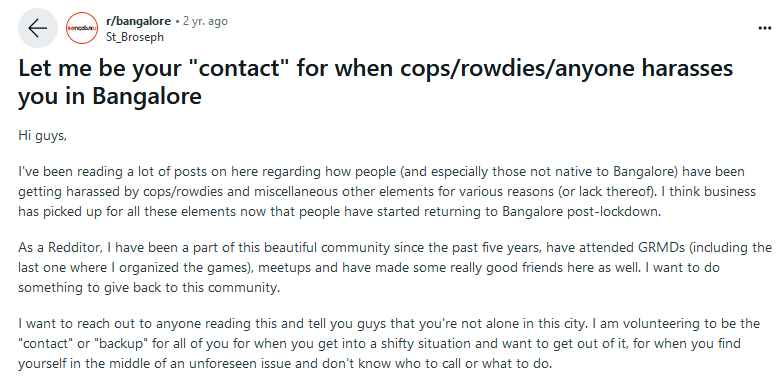

And thus we arrive at December 11, 2021. Bulker, whose real name is Dushyant Dubey, started a new thread on the r/bangalore subreddit:

Bangaluru is a city in flux, with a large number of young people moving here to work at the IT companies and startups that make it India’s Silicon Valley. Many of these kids are away from home for the first time, and do not have a local “contact” that protects their interests from landlords, PG owners, cops, rowdies (slang for street thugs), MLA’s, <insert goon group here>. An immigrant himself, Dubey understood these problems intimately.

He offered to be of help, to anyone and for anything. The requests started coming in, small and big, with many users tagging him in relevant threads using his delightfully named handle – u/St_Broseph.

Someone needed help filing a police complaint. Another user needed therapy but couldn’t afford it. Broseph happily paid out of his own pocket. One young woman had been sexually harassed by a policeman, and broseph helped escalate the issue and make sure the complaint was registered and acted upon. He even maintains a safehouse for people in distressed situations.

Between representing common folks in disputes with politicians, and (I kid you not) rescuing kittens, broseph has done it all. Following the suicide of Aditya Prabhu, he organised a protest to spur the investigation and formed a student support group. The r/bangalore community loves him- many people volunteer time and money towards his efforts. They call themselves the St.Broseph Army, and have a HQ and everything.

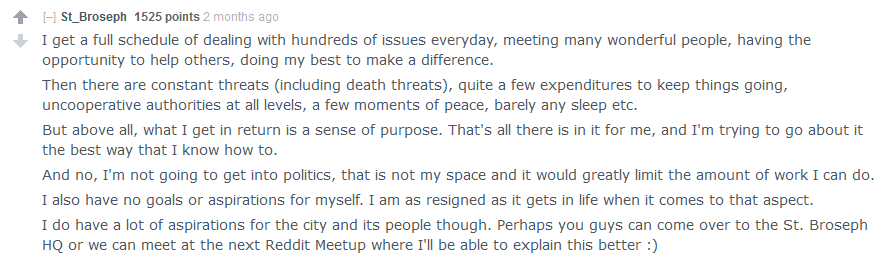

What’s next for broseph? In his own words:

Here’s a toast to Bengaluru’s Batman: not the hero we deserve, but definitely the one we need right now.

I’ll end with a quote by Mr. Rogers:

Note: This post originally appeared on Internet Stuff.

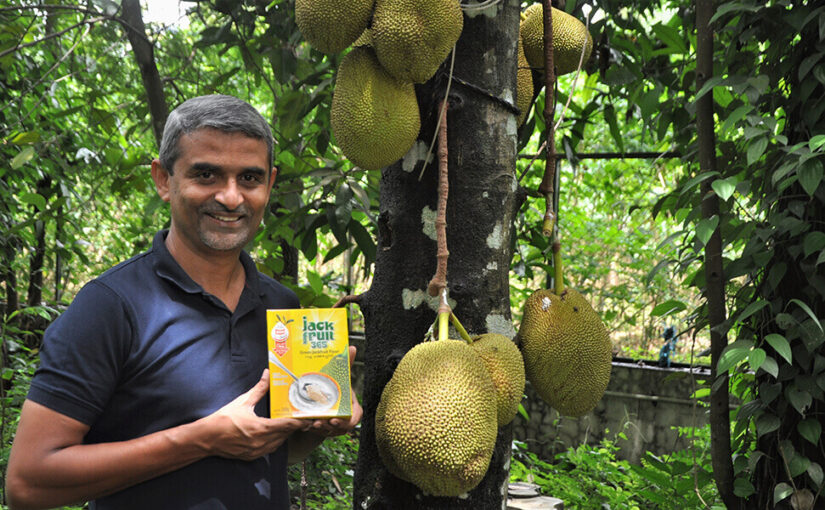

The young entrepreneur from Jharkhand who wants to simplify spiky jackfruit for India

Like most young people born and raised in Jharkhand, Aman Chhabra, 31, was determined to find the escape velocity required to pull out of the state’s dark gravitational forces that could ground even modest ambition.

Being a bright student, he managed to attend Delhi’s prestigious Shriram College of Commerce. Post graduation, when he was expected to become a part of the family business running a hotel in Ramgarh, a town in central Jharkhand, Chhabra chose a career in event management instead.

His small but profitable startup organized flashy weddings for the super-rich in Mumbai and Delhi where A-list artistes performed and fine wine flowed from faucets. But the business couldn’t survive the crippling effect of Covid-19 in 2020. The search for a business idea that could survive such unforeseen shocks, and in sync with his own newfound life-motto of minimalism drove him to seek shelter under the copious, cool canopy of the jackfruit tree.

Chhabra has joined the burgeoning corps of food entrepreneurs that wants to rekindle India’s love for the spiky, smelly, latex-laden sticky jackfruit.

His latest startup Kathalfy, seeks to simplify the consumption of jackfruit, called kathal in Hindi, in the form of ready-to-eat vegan packaged foods such as patties, keema masala, jackfruit makhni and assorted Indian curries.

Read the full story here

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/

A Kerala entrepreneur’s jackfruit startup that’s fighting India’s diabetes ‘pandemic’

Come summer, Indians engage in a unique mango one-upmanship: Alponso or Langda; Ratnagiri or Devgarh Alphonso; Gujarati Kesar or Banarsi Chausa. If you ask me, this kind of mango tribalism is trite. The mango season is short. Eat whatever you can find.

But this is also the season of jackfruit, a fruit far more complex in flavour, and a veritable super food that Indians in its native land love to despise. Jackfruit of course has an exalted status in traditional Tamil literature, alongside banana and mango. Jackfruit can grow prolifically anywhere in peninsular India and the mid-to-lower Gangetic belt, pretty much.

I’ll share a couple of The Plate’s jackfruit stories here.

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/

Land of the Free, Home of the Brave

How a small, sleepy town in Karnataka turned into the vegetable nursery of India

The right socio-economic conditions, availability of trainable talent, clement weather all year-round and a pioneering entrepreneur’s vision to harness it all setting up a sunrise-sector business turns a dozy place into a prosperous hub of startups. This isn’t yet another paean to Bengaluru’s status as the ‘Silicon Valley’ of India. It is the story of a place smack in the geographical centre of Karnataka, 300km to the northwest of Bengaluru called Ranebennur that’s the epicentre of India’s hybrid vegetable seed production.

Since seeds are the most critical and fundamental unit of input in agriculture, it would not be an exaggeration to call such a place ‘startup town’.

Seeds of success

Ranebennur is where India’s largescale, commercial production of hybrid vegetable seeds began in the late 1970s. Today, most major national and multinational agriculture companies from Syngenta to Pioneer to Namdhari have operations in the region. The farmers in this small region produce roughly Rs 500-crore worth of hybrid seeds of vegetables such as tomatoes, chillies, brinjal, okra and assorted gourds.

Such is the economic impact of hybrid seed companies on the local economy that it is common to find homes bearing homage to them. A seed company’s name inscribed in concrete suffixed with the word ‘krupe’ (benevolence) on the forehead of concrete homes painted in bright Vaastu-compliant colours ranging from parrot green to lemon yellow and Barbie pink isn’t a rare sight.

All of it is thanks to Manmohan Attavar a pioneering horticulture scientist and entrepreneur who must rank alongside MS Swaminathan and Verghese Kurien in the pantheon of modern India’s agriculture renaissance figures.

Read the full story here about how a pioneering Indian scientist-entrepreneur turned a non-descript town in Karnataka into India’s vegetable garden.

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/

Pakistan; Myths and Consequences

This was an old article i wrote for the Indian magazine Pragati in 2013. That magazine has since disappeared, but some good Samaritan found this on the intertubes and I thought I would post it here for posterity. Some elements of my thinking have changed since then, and others have shifted in intensity, but i am posting this article as originally written;

Salman Rushdie famously said that Pakistan was “insufficiently imagined”. To say that a state is insufficiently imagined is to run into thorny questions regarding the appropriate quantum of imagination needed by any state; there is no single answer and at their edges (internal or external), all states and all imaginings are contested. But while the mythology used to justify any state is elastic and details vary in every case, it is not infinitely elastic and all options are not equally workable. I will argue that Pakistan in particular was insufficiently imagined prior to birth; that once it came into being, the mythology favored by its establishment proved to be self-destructive; and that it must be corrected (surreptitiously if need be, openly if possible) in order to permit the emergence of workable solutions to myriad common post-colonial problems.

In state sponsored textbooks it is claimed that Pakistan was established because two separate nations lived in India — one of the Muslims and the other of the Hindus (or Muslims and non-Muslims, to be more accurate) and the Muslims needed a separate state to develop individually and collectively. That the two “nations” lived mixed up with each other in a vast subcontinent and were highly heterogeneous were considered minor details. What was important was the fact that the Muslim elite of North India (primarily Turk and Afghan in origin) entered India as conquerors from ‘Islamic’ lands. And even though they then settled in India and intermarried with locals and evolved a new Indo-Muslim identity, they remained a separate nation from the locals. More surprisingly, those locals who converted to the faith of the conquerors also became a separate nation, even as they continued to live in their ancestral lands alongside their unconverted neighbours. Accompanying this was the belief that the last millennium of Indian history was a period of Muslim rule followed by a period of British rule. Little mention was made of the fact that the relatively unified rule of the Delhi Sultanate and the Moghul empire (both of which can be fairly characterised as “Muslim rule”, Hindu generals, satraps and ministers notwithstanding) collapsed in the 18th century to be replaced in large sections of India by the Maratha empire, and then by the Sikh Kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Continue reading Pakistan; Myths and Consequences

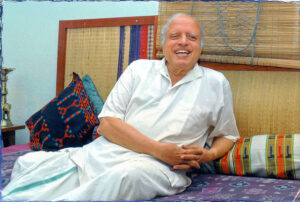

MS Swaminathan: architect of Green Revolution; the greatest Indian since Gandhi

On the occasion of India’s 65th anniversary of Independence, television channels CNN-IBN (now CNN News18), History Channel, and Outlook magazine jointly ran an audience poll, steered by a panel of “experts”, to ascertain the ‘Greatest Indian after Gandhi’.

Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan, who passed on at the age of 98 on September 28, 2023, barely made it to a shortlist of 50, let alone the Top 10 that contained Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar in a club overwhelmingly comprising politicians.

Such lists are gimmicks anyway and a result of political partisanship, recency bias and media narratives.

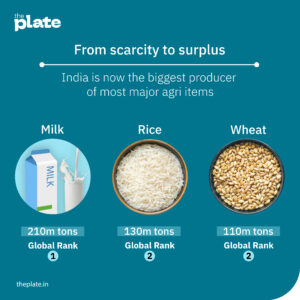

In this writer’s view, with no disrespect to those of yours, there isn’t anyone more worthy of the tag ‘greatest Indian since Independence’ than Dr MS Swaminathan. He provided the bedrock of science and built institutions up from scratch with scant resources to usher in the Green Revolution. His contributions made India not just food self-sufficient, helped 800 million poor escape hunger, but also turned it into a leading producer of every major agricultural commodity.

Faith and food

Swaminathan can be seen as the male embodiment of Annapoorna, a form of Parvati, the Hindu deity of food and nourishment, holding in one hand a Leitz binocular research microscope and his field notes in another, instead of the pot and ladle filled with food in popular religious iconography.

That both the Goddess of nourishment and Swaminathan, the scientific guarantor of food security, are now relegated in public consciousness is a measure of India’s progress and the liberty we now have to take access to food for granted.

Read the full story here

Follow ThePlate.in to understand India from farm to plate!

X: https://twitter.com/thePlateIndia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theplateindia/