Friends,

The spirit of Brown Pundits has always been dialogue — open, searching, and at times, fierce. But dialogue only flourishes when it is consistent and principled.

Recently, a contradiction has emerged in Kabir’s contributions: applying one set of standards to India and Pakistan, and a different set to Israel. This has led to repeated cycles of disruption, rather than genuine exchange.

To preserve the integrity of our space, Kabir’s participation will be paused until this inconsistency is clarified (we will remove any of his comments that do not address and acknowledge the contradiction; we will also remove any replies to his comments). This is not censorship, but stewardship. Free speech here is not about endless repetition; it is about coherence, accountability, and respect for the whole.

🕊️ On Confirmation, Coincidence, and the Return of Brown Pundits

Exactly one year ago today, 17 September 2024, I published a piece titled “The Battle for the Taj Mahal: India’s Sacred Lands & Waqf Boards Under Fire”.

At the time, Brown Pundits was stirring from hibernation. Readership had dwindled to near-zero, the commentariat was dormant, and the site, once lively and interrogative in its heyday, felt like a forgotten archive. That post, like so many others before it, was written in solitude. There was no traction, no expectation. Just thought, laid down with care.

And yet here we are, one year to the day, and the blog has roared back to life.

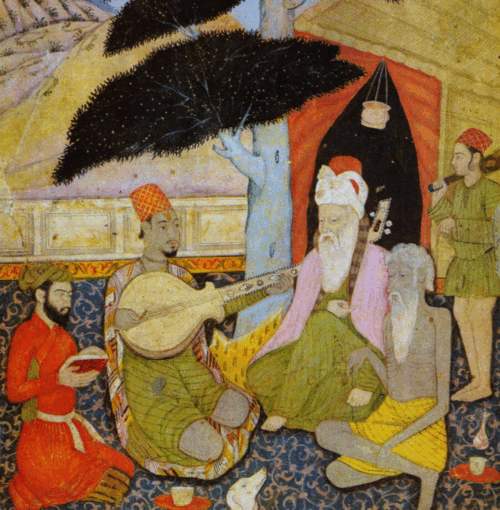

📿 What the Baháʼí Tradition Calls “Confirmation”

In the Baháʼí tradition, we don’t reduce these moments to mere coincidence. Instead, we speak of confirmation; divine endorsement coupled with meaningful alignment. A subtle assurance that what was offered in silence may still echo in relevance.

Sometimes, truth takes time. It must be planted, and it must ripen. And then, if the conditions are right, it re-emerges at the very moment it’s needed again.

🏛️ Revisiting the Taj & the Sacredness of Land

That post, exploring Waqf Boards, sacred lands, and the Taj Mahal’s place in India’s civilizational memory, was written in a moment of saturation. Too many headlines, too little context. My intention wasn’t to settle the argument, but to recast it: What makes land sacred? Who has the right to remember? Who gets to reclaim?

Reading it now, what’s striking is not just how relevant it remains, but how the same debate has reassembled; not just thematically, but almost ritually, with new voices circling back in familiar orbits.

🌀 Same Debate, Same Deflection

And so we arrive back, with uncanny symmetry, to Kabir. He’s long argued that nations must be judged by their own internal frameworks: Continue reading 🗓️ One Year Ago Today: The Taj Mahal, Sacred Lands, and the Power of Timing