(Originally published at Naya Daur, whose website was blocked by PTA in Pakistan a day after this was published).

“In every country, the textbook is the primary implement of education at the school and pre-university stages of instruction. In Pakistan, it is the only instrument of imparting education on all levels, because the teacher and the lecturer don’t teach or lecture but repeat what it contains and the student is encouraged or simply ordered to memorize its contents. Further, for the young student the textbook is the most important book in his little world: he is forced to buy it, he carries it to the classroom every day, he has to open before him when the teacher is teaching, he is asked to learn portions of it by rote, and he is graded by the quantity of its contents that he can regurgitate.”

This was how Pakistani historian K.K. Aziz started his groundbreaking work The Murder of History: A critique of history textbooks used in Pakistan. The book was published 25 years ago (in 1993) and the only change in the role of textbooks since then is that provinces were granted the right to formulate their own textbooks under the 18th amendment to the Constitution. Another significant change in the last two decades has been the mushrooming of private schools that use textbooks different from the official ones.

History doesn’t start with Muhammad bin Qasim

While textbooks for natural science subjects — like Physics, Chemistry and Biology — or those pertaining to language studies are less likely to form a child’s worldview, textbooks for history and “social studies” (a mixture of history, civics and geography) are supposed to be the first step toward a social conscience.

In the textbooks that my father’s generation studied, history textbooks did not start with the year 712 A.D., when Muhammad bin Qasim invaded Sindh. They contained history of the Indian Subcontinent before that particular event. They were also devoid of chapters devoted to the ‘Ideology of Pakistan’ and other such vague ideas.

But the distortion of history in Pakistan started as soon as the country came into being. On the 17th of August, 1947, a mere three days after Independence, an article written by Mr. Abdullah Qureshi was published in national newspapers, titled “Textbooks of History and Need for Reform”.

The atrocity that was Abdullah Qureshi

In that article, Mr. Qureshi argued, “The person who knows the Islamic history accurately, would prove to the best citizen of Pakistan. He will not commit any act against the state of Pakistan. His heart would be filled with love for Islam and Muslims and he would not even think about treason. In my view, it is imperative that history of Muslims should be popularized as it will lead to strengthening Pakistan. Every citizen should be made aware of Glorious Islamic Traditions. Every Citizen should be reminded that straying from National Interest would lead to destruction of the Nation.”

He further wrote, “The history that is taught to our children in schools is not factual. It is based on propaganda spread by the British and it serves to justify British Imperialism. It is based on personal biases of British Historians. As a result, worthless events have been presented as glorious occasions. It promotes a false Hindu-Muslim parity, while the fact is that before arrival of Muslims, Hindus did not have any authentic history or collection of traditions. Due to need of the hour, British historians concocted false narratives to appease the Hindus.”

The British periodized Indian history

Now it is interesting to note that Mr. Qureshi rails against the biases of British historians, and yet, falls back on a form of Indian historiography invented by them. After all, as Dr. Mubarak Ali wrote in an article:

“The periodization of the Indian history as the Hindu, the Muslim, and the British was not done by any Hindu historian but by a British historian, James Mill, the author of the “History of British India”. He intentionally divided the history on religious basis, but did not call the British period a Christian period in order to keep a secular outlook, and to maintain a balance between these two opposite religious communities. This periodization is challenged and severely criticized by a Hindu Historian [sic], Romila Thapar. In India, historians no more use these terminologies whereas in Pakistan historians persist to use them”

Following the debacle of 1971, textbooks were modified to rationalize the separation of East Pakistan as a ‘Hindu Conspiracy’

Nevertheless, the project of historical revisionism proposed by Abdullah Qureshi was, indeed, put into motion in Pakistan.

Distortion of History to rationalize the Fall of Dhaka

K.K. Aziz analyzed history textbooks written during the period 1960–1990 and he found factual errors in most of these books. Distortion of history had started soon after Independence but the particular ideological tilt that we are today most familiar with started in the 1970s. Following the debacle of 1971, textbooks were modified to rationalize the separation of East Pakistan as a ‘Hindu Conspiracy’. This obfuscation was intended to whitewash the atrocities committed upon Bengalis starting from 1947.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to power amidst political confusion with an Islamic socialist programme, promising to build a new Pakistan and to address the economic and political issues facing the country at the time. The result was an over-emphasis on a separate “Pakistani identity” and a new description of “the enemy” so as to unify the nation. The strategic use of Islam in education policy started during the era of General Ayub Khan and continued during the Bhutto period.

Manufacturing a false pride?

The worst of the rot truly set in during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime during the period 1977–88. Dr. Parvez Hoodbhoy and A.H. Nayyar mention in their book “Rewriting the History of Pakistan” in Islam, Politics and the State: The Pakistan Experience (published in 1985):

“In 1981, General Zia-ul-Haq declared compulsory the teaching of Pakistan studies to all degree students, including those at engineering and medical colleges. Shortly thereafter, the University Grants Commission issued a directive to prospective textbook authors specifying that the objective of the new course is to ‘induce pride for the nation’s past, enthusiasm for the present and unshakeable faith in the stability and longevity of Pakistan’. To eliminate possible ambiguities of approach, authors were given the following directives:

To demonstrate that the basis of Pakistan is not to be founded in racial, linguistic, or geographical factors, but, rather, in the shared experience of a common religion. To get students to know and appreciate the Ideology of Pakistan, and to popularize it with slogans. To guide students towards the ultimate goal of Pakistan — the creation of a completely Islamised State.

Islamization of Science books

As a result of this ideological onslaught, even the books of science were “Islamised”. Specific chapters have been dedicated in books of Physics, Chemistry and Biology, introducing young students to Muslim Scientists. Most of these “Muslim Scientists” were a product of the Mu’tazilla tradition in the medieval period, a fact that is not included in any of the introductions.

Any effort to reform the current textbooks should ideally cleanse all the waste material that the books have accrued in the last 65 years.

The ideological propaganda that has plagued the textbooks has also contributed to a confused state of mind among the next generation of Pakistan. It is not a co-incidence that according to a survey of educated youth by Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies, “A sizeable percentage of the survey population believed that religion should be the only source of law in Pakistan.”

How distortion of History begets fundamentalism

The British Council released a report in November 2009 titled “Pakistan: The Next Generation” focusing on issues surrounding the youth in Pakistan. The report also noted, worryingly, that “Disillusion with democracy is pronounced. Only around 10% respondents have a great deal of confidence in national or local government, the courts, or the police. Only 39% voted in the last election.” Another report by the British Council in 2013 mentioned that “38% respondents expressed a desire for implementation of Shariah as opposed to parliamentary democracy with 29% respondents opting for continuation of Democratic system.”

Confusion has led to identity crisis

Any effort to reform the current textbooks should ideally cleanse all the waste material that the books have accrued in the last 65 years. It is expected to be a Herculean task and it requires a great deal of willingness from the provincial governments.

The insertion of exclusionary modes of thinking and petty ideological narratives in textbooks has resulted in the emergence of a confused, disillusioned and restless educated class of Pakistanis. Textbooks have become a contested space for ideological skirmishes in the last few decades. The educated youth of Pakistan faces a dilemma when confronting realities on the ground — because they have been taught a very different narrative. This national confusion has led to a widespread identity crisis.

Meanwhile, in an Islamiyat textbook for undergraduate students in Punjab, the introduction to the book states, “Pakistan is an ideological state. It has been founded on the pattern established in Madinah.”

- According to a Pakistan Studies textbook used in Punjab, something known as “Nazriya Pakistan” (Ideology of Pakistan) is based on Islam, which itself is claimed to be a complete code of life.

- In an Islamiyat textbook for undergraduate students in Punjab, the introduction to the book states, “Pakistan is an ideological state. It has been founded on the pattern established in Madinah.”

- A sociology textbook for the Intermediate level in Punjab paints the Baloch people, citizens of Pakistan, as ‘looters’.

These are but a few examples of the pernicious ideological conditioning that these textbooks perform.

ANP’s improvements to curriculum in KP rolled back by PTI

In the aftermath of the 18th amendment, provincial governments were provided an opportunity to make amends. In the case of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the Awami National Party (ANP) government during 2008–2013 made some positive changes in the curriculum — driving the focus away from religious militarism towards an ideal of coexistence and peace. But, following the rise to power of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government in that province, most of those gains were reversed under the influence of religious parties allied to the PTI.

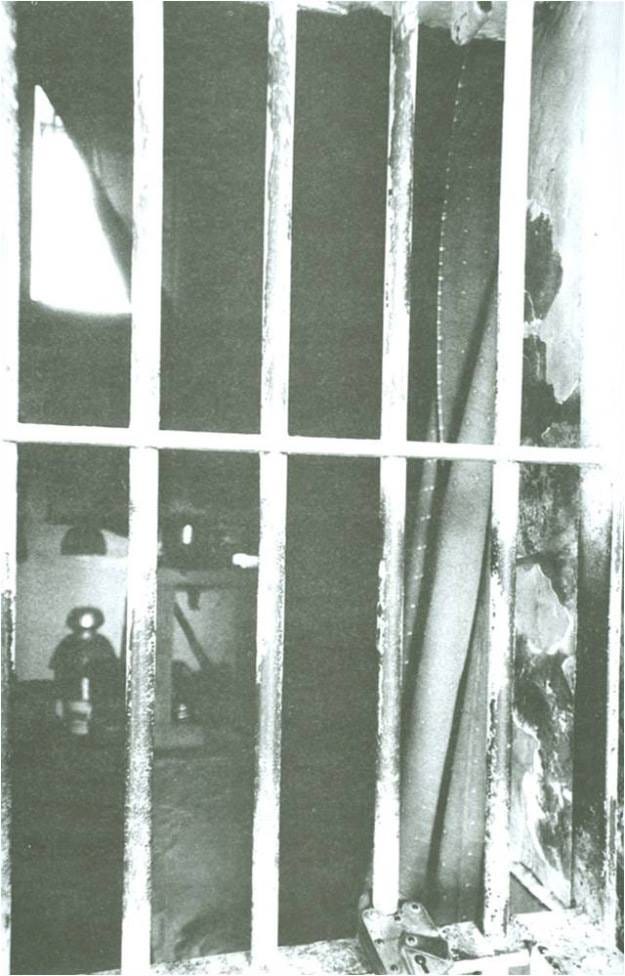

The upper one is a picture of a KP textbook from ANP era, terming Jinnah a ‘secular liberal barrister’ who ‘also seemed to advocate the separation of the church and the state’. Below is the current version of the same book where the ‘secular liberal’ has been replaced by ‘competent’ while ‘separation of the church and the state’ has been replaced by ‘ideology of Pakistan’. — Picture courtesy: Omer Qureshi

In Punjab, according to Dr. Hoodbhoy, textbooks have been “improved considerably”, moving beyond some of the worst dogma. One hopes that this experiment is implemented nationwide and Pakistan’s next generation is taught according to the finest international standards of education — where there is little room for deliberately conditioning young students into authoritarian, theocratic and racist mindsets.