On 28 December 2010, the question was not ideology or politics, but naming.

brownpundit(s). brownguru(s). brownsmarts. brownfolks. brownidiots.

The instinct was already there: reclaim brown without asking permission, and refuse the performance of respectability that so often polices minority intellectual spaces. The reply came quickly and decisively.

Brownpundits.

The first post, Hello World, went live on 30 December 2010. Fifteen years later, what matters is not that a blog survived. Many do. What matters is how it survived: without institutional backing, without funding, without ideological capture, and without deference to credentials masquerading as truth. Brown Pundits was never designed as a platform for prestige. It was designed as an intellectual retreat; a place where arguments stand or fall on substance, not accent; where brownness is neither explained nor apologised for; where disagreement is not heresy. That posture, upright, unbought, unafraid, is why Brown Pundits still exists.

A Discipline, Not a Brand

Brown Pundits began with a simple wager: that the English-language internet still had room for a South Asian intellectual space that did not need permission. No institutional sponsor. No ideology police. No professional incentives. Just writers who believed that brown questions, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, diasporic, could be argued in public with rigor and dignity. Fifteen years on, Brown Pundits remains. That endurance is not luck. It is structure. We lasted because we never built this as a brand. We built it as a discipline.

The point has never been agreement. The point has been posture: stand upright, test claims, correct errors, refuse theatre. Independent platforms fail for predictable reasons. They chase virality. They harden into faction. Or they monetize attention until thought becomes marketing. Brown Pundits avoided those traps by being unusually boring in the right ways: we publish, we argue, we edit, we keep the record. Nobody here is paid to write. That is not moral vanity. It is why we remain unpurchasable.

Five Years of Solidarity

Over the last five years, some of the most important work has not been online at all. It has been the steady, unglamorous work of civic seriousness: reading dense documents, tracking deadlines, understanding procedure, and watching institutions scramble when they assume nobody is paying attention. During this period, there has also been sustained dialogue with a small circle of intellectually serious allies; quiet, exacting minds with a gift for clarity under pressure and an instinct for how power hides behind process. Not public figures. Not brands. Just adults: difficult to gaslight, uninterested in theatrics, precise about the record.

That kind of solidarity resets the baseline. You stop mistaking polish for integrity. You stop confusing titles with truth. You learn to clock everything. You learn that the record is not drama; it is protection. That discipline carries back into Brown Pundits. It shows in how disputes are handled, how errors are named, and how authority is tested rather than absorbed.

The SD Episode as Proof

The recent SD exchange was not, in the end, about architecture. It was about authority: who is allowed to explain, who is expected to absorb, and what happens when the subject speaks back. We engaged the way Brown Pundits always has. We read closely. We identified the errors. We insisted on precision. We treated the exchange as part of the record, not as outrage content. What mattered was not that corrections were made; corrections are normal and welcome.

What mattered was the instinct that surfaced at the start: revise quietly, respond pedagogically, assume the critique will not notice the shift. That instinct is older than any one writer. It is a patterned behaviour in how authority manages challenge in brown-facing spaces. And yet, precisely because Brown Pundits exists, the record held. The language moved. The posture changed. This was not a “victory.” It was proof of concept. The platform did what it is meant to do.

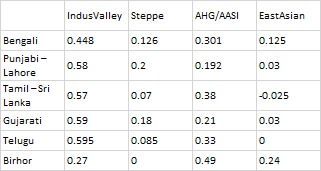

“Brown” Is Not an Ethnicity; It Is a Civilizational Composite

The deeper reason Brown Pundits still matters is that brown is not a neat identity. It is not a single bloodline, doctrine, or grievance. It is a civilizational composite with a long memory and a hard geography. The Indian subcontinent is layering, not essence:

-

ancient coastal and inland populations

-

Dravidian continuities and transformations

-

Aryan synthesis and institutionalisation

-

Islamicate overlays that became native in texture, not merely foreign in rule

-

British power, whose administrative afterlife still structures class and accent

And beyond this lie the East, the Northeast, the mountain corridors, the sea routes. This is why Brown Pundits resists simplification. The subcontinent is not a monoculture, a single trauma, or a single pride. It cannot be narrated by those who treat it as a site for extraction; political, academic, or aesthetic.

What Fifteen Years Means

Fifteen years is long enough to know what this site is for. Not fame. Not power. Not money. Not outrage. Those are cheap forms of relevance. Brown Pundits exists to keep an alternative alive: an intellectual retreat on the open web where brown life can be examined with seriousness; where hierarchy is not mistaken for truth; where criticism is not treated as insolence; where the record matters. We are not untouchable, and we do not aim to be. But we are not easily compromised, because everyone here has a life outside the internet. That is our freedom. Fifteen years on, the mission remains unchanged:

Stand upright | Read closely | Correct what is wrong | Refuse permission structures | Keep the record |

That is why we are still here.